Authors: Samantha Wahlers & Phillip McMullen MD

Background

Obesity refers to an increased amount of fat distributed throughout the body. Obesity is primarily defined by an individual’s BMI (body mass index), which is a relatively suboptimal metric as BMI does not indicate the distribution of fat in the body but rather the individual’s gross weight in relation to their height. The distribution of body fat is also an important factor, with visceral adiposity distribution being associated with a poorer prognosis. Below are the criteria that take into account both height and weight:

BMI Classification

- Underweight: BMI <18.5 kg/m2

- Normal: BMI 18.5 – 25 kg/m2

- Overweight: 25-30 kg/m2

- Obese: >30 kg/m2

- Class I: 30 – 34.9 kg/m2

- Class II: 35 – 39.9 kg/m2

- Class III: >40 kg/m2

- Morbid obesity: >40 kg/m2 or >35 kg/m2 with associated comorbidities

Obesity is not synonymous with metabolic syndrome, as obesity can occur in the setting of a metabolically healthy individual. However, patients with obesity frequently experience metabolic conditions that affect multiple organ systems throughout the body. Below is a quick reference table of the major organ systems affected.

| System | Pathologies |

| Cardiovascular |

|

| Endocrine | |

| Hepatic |

|

| Musculoskeletal |

|

| Pulmonary |

|

| Renal |

|

| Cancer |

|

Quick Tips at Time of Autopsy

Establishing obesity at autopsy is not as straightforward as it may seem. The clinical history of obesity, based on documented BMI, is usually validated at autopsy with weight/height measurements in the autopsy suite. However, additional measures of adiposity have been proposed. These include

- Central adiposity: Measure the circumference of the abdomen at the level of the umbilicus then use the Waist-to-Hip Ratio (ratio of the waist circumference to the hip circumference) or the Waist-to-Height Ratio (ratio of waist circumference to height; it suggests central obesity when >0.5).

- Subcutaneous fat thickness measured at the umbilicus (i.e. abdominal fat pad): Measurement of the fat pad thickness may be a better representation of central adiposity and accounts for lean muscle mass better than BMI alone

- Fat mass percentage: An uncommonly used technique which weighs the fat at the time of autopsy to determine adiposity

Distinctions in how adiposity is measured are important, as BMI has repeatedly been found to be a poor predictor of, for example, cardiovascular events, while measures of central adiposity appear to be more reliable.

Clinical History

- Causes of obesity

- Sequelae of obesity

- Genetic Disorders such as Prader Willi Syndrome, Fragile X Syndrome, Wilson-Turner Syndrome, Alstrom Syndrome, Leptin Deficiency

- High Levels of Stress

- Sequelae of obesity

- Insomnia

- Obstructive sleep apnea

- Hypertension

- Diabetes Mellitus

- Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

- Elevated liver function tests (ALT and AST; ALT may be higher than AST in contrast to alcoholic steatosis)

- Dyslipidemia and atherosclerosis

- Sudden cardiac death: prolonged QT interval on ECG

- Osteoarthritis with or without subsequent joint replacements

- Certain malignancies especially esophageal & gastric adenocarcinoma, endometrial cancer, and liver cancer

External Exam

Special considerations at autopsy

- May require larger tables, scales, and lifts to assist with moving the body

- Excess tissue makes areas such as the back, perineum, and genitals more challenging to examine

Findings

- Obesity leads to increased androgens (testosterone and estrogen)

- Acne (Elevated androgens stimulate sebaceous gland activity, leading to increased oil production and clogged pores)

- Hirsutism (Elevated testosterone and dihydrotestosterone levels cause excessive hair growth in a male-pattern distribution)

- Gynecomastia (In obese individuals, aromatase activity in adipose tissue converts androgens to estrogens)

- Insulin resistance

- Skin tags (Associated with both obesity and diabetes mellitus: insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia stimulate growth factor pathways, such as IGF-1, leading to proliferation of epidermal cells)

- Acanthosis nigricans (Chronic hyperinsulinemia increases signaling through insulin and IGF-1 receptors in the skin. This causes keratinocyte and dermal fibroblast proliferation, resulting in thickened, hyperpigmented skin, often in the neck, axillae, and groin)

Images: (Left) Poorly demarcated hyperpigmented patches called acanthosis nigricans pictured on a lighter skin complexion. (Right) Acanthosis nigricans on a darker skin complexion. (Image credits: (Left) Scott Dulebohn from StatPearls. (Right) Shyam Verma from StatPearls).

Images: (Left) Poorly demarcated hyperpigmented patches called acanthosis nigricans pictured on a lighter skin complexion. (Right) Acanthosis nigricans on a darker skin complexion. (Image credits: (Left) Scott Dulebohn from StatPearls. (Right) Shyam Verma from StatPearls).

- Structural alterations

- Abdominal striae (stretch marks)

- Pedal edema (Obesity increases intra-abdominal pressure, reducing venous return from the lower extremities)

- Stasis dermatitis (Obesity increases the risk of venous hypertension, leading to blood pooling in the lower extremities. Prolonged venous stasis results in capillary leakage, hemosiderin deposition, and chronic inflammation, manifesting as reddish-brown discoloration and skin thickening.)

- Varicose veins

- An enlarged neck circumference (≥17 inches in men or ≥16 inches in women) may suggest obstructive sleep apnea

- Bowlegs (genu varum): Resulting from mechanical stress and altered weight distribution.

- Flat feet (pes planus): Due to excessive weight and strain on foot arches.

- Careful examination of the underside of panniculi should be undertaken in order to characterize any occult skin infections.

- Intertrigo: Inflammation or irritation in skin folds (e.g., under breasts, abdomen, or groin).

- Fungal infections (e.g., candidiasis): Common in skin folds due to warmth and moisture.

- Cellulitis: Localized skin infections

- Ulcers: Especially venous stasis ulcers on the medial malleolus.

Internal Examination

Heart

- Atherosclerosis

- Myocardial Infarction

- Obesity related cardiomyopathy

- A grossly “globoid” heart due to biventricular hypertrophy and dilation often with left ventricular fibrosis (seen grossly or histologically) and left atrial dilation (the latter is due to both to an expanded intravascular volume and to altered LV filling properties)

- Right ventricular hypertrophy may be seen in the setting of cor pulmonale/obstructive sleep apnea

- Left ventricular concentric hypertrophy may be seen in the setting of hypertension

- Obesity will increase the size of the heart. However, it does not mean that it always results in cardiomyopathy – some alteration in size can be a physiologic response to increased work. In patients with obesity and fatal arrhythmias and otherwise negative autopsies (sudden cardiac deaths from obesity), studies have shown that their hearts are larger – both in weight and ventricle wall thickness – compared to age and BMI matched controls who did not have fatal arrhythmias (Goel 2023). For this reason, it is important to use an organ weight table that includes obese, but otherwise healthy, individuals so that the percentiles reflect the increase in weight that is pathologic and not just obesity-related.

- Fatty infiltration of the myocardium

- Important to consider and exclude inheritable conditions resulting in increased myocardial adipose tissue, such as arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia (ARVC/D)

Image: Gross and Microscopic Findings in Individuals With Unexplained Cardiomegaly in Obesity. The top row demonstrates not only an increase in size of the organ, but the rounded “globoid” shape of the heart due to biventricular dilation. The latter is not seen in a heart that is from someone with obesity but not cardiomyopathy of obesity. Cross sections, shown in the second row, further demonstrate the biventricular dilation. (Image credit: Westaby 2023).

Image: Gross and Microscopic Findings in Individuals With Unexplained Cardiomegaly in Obesity. The top row demonstrates not only an increase in size of the organ, but the rounded “globoid” shape of the heart due to biventricular dilation. The latter is not seen in a heart that is from someone with obesity but not cardiomyopathy of obesity. Cross sections, shown in the second row, further demonstrate the biventricular dilation. (Image credit: Westaby 2023).

Lungs

- Hypoventilation leads to pulmonary hypertension & fibrosis

- Pulmonary embolism (due to hypercoagulability with obesity)

Systemic

- Hypertension

- Diabetes mellitus

- Lipomatoses including heart (increased epicardial fat), pancreas (fat infiltration), and/or liver (hepatosteatosis)

Musculoskeletal

- Osteoarthritis: visible osteophytes and/or joint replacements

Histologic Evaluation

Heart

- Obesity Cardiomyopathy: Non-specific left ventricular fibrosis (seen grossly or histologically), adipose infiltration, and myocyte hypertrophy

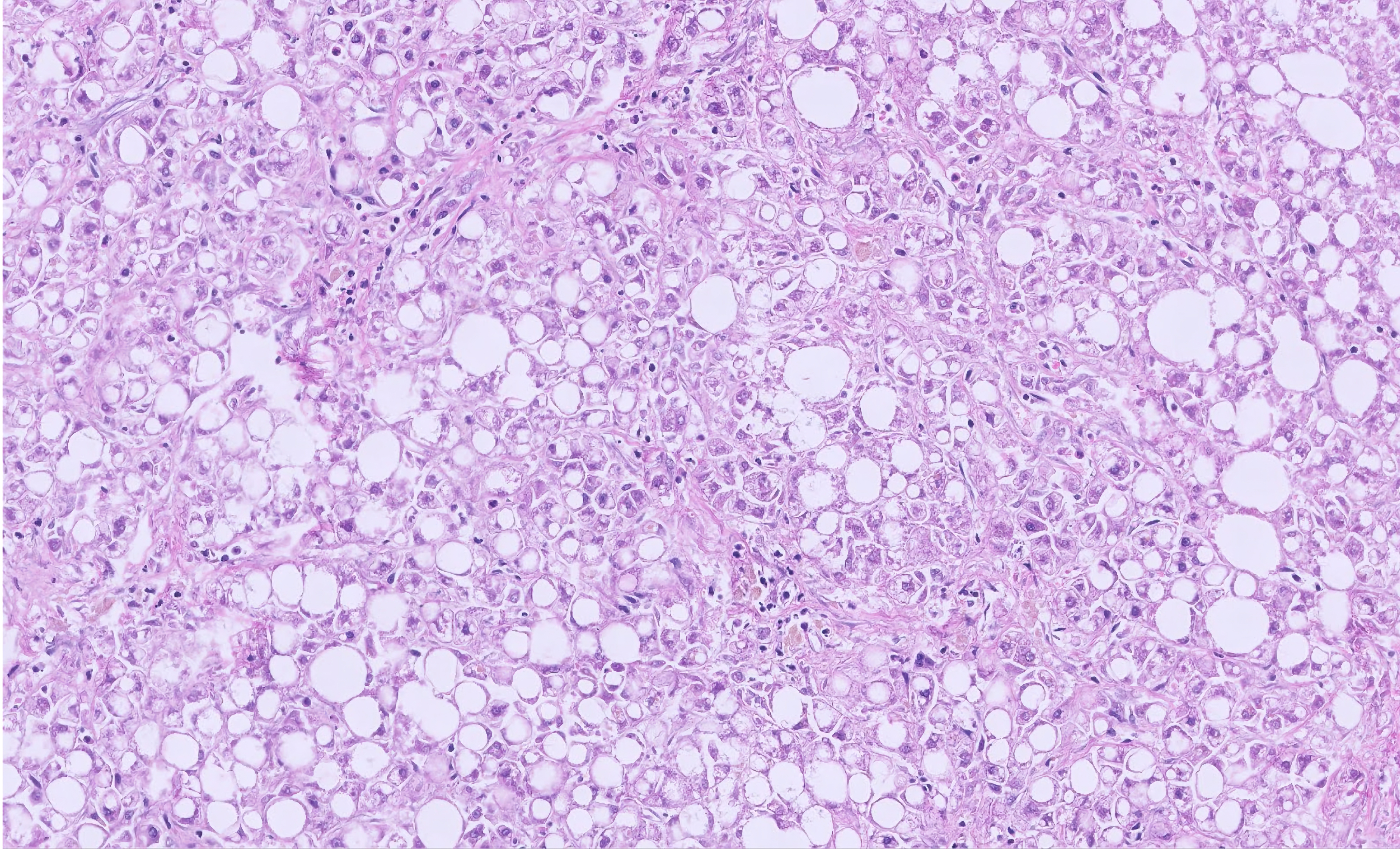

Liver

- Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NASH) and Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

| Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH) | Alcoholic Steatohepatitis (ASH) | |

| Steatosis | Predominantly macrovesicular steatosis | Predominantly macrovesicular steatosis but sometimes microvesicular steatosis is prominent |

| Inflammation | Lymphocytic infiltrates are more common | Neutrophilic infiltrates predominate, often surrounding ballooned hepatocytes |

| Ballooning degeneration | Present in both but more pronounced in NASH | |

| Fibrosis | Perisinusoidal fibrosis in Zone 3, but portal fibrosis may be more prominent as disease progresses | Perivenular and perisinusoidal fibrosis in Zone 3 (centrilobular region) is characteristic |

| Mallory-Denk Bodies | Seen in both but traditionally more associated with ASH | |

| Iron deposition | May be more prominent in ASH |

- A Trichrome can help visualize fibrosis (see the cirrhosis article for more information) and Oil Red O or Sudan Black can visual adipose on frozen section

Image: Hepatic steatosis is easy to identify with routine stains. The clear spaces from adipocytes remain even in a background of autolysis, making grading the steatosis possible even with significant post mortem intervals. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/Stanford University).

Image: Hepatic steatosis is easy to identify with routine stains. The clear spaces from adipocytes remain even in a background of autolysis, making grading the steatosis possible even with significant post mortem intervals. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/Stanford University).

Kidney

- Obesity-related glomerulopathy: enlarged glomeruli from mesangial expansion and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Cross-section of glomeruli are >½ of a 40x high power field. Mild thickening of glomerular basement membrane may be seen.

Image: Obesity related glomerulopathy with basement membrane thickening. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/Stanford University).

Image: Obesity related glomerulopathy with basement membrane thickening. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/Stanford University).

Tips at Time of Reporting

- Obesity should be listed if it likely caused or contributed to the death

- If BMI > 30 and the patient had dilated cardiomyopathy, say “Cardiomyopathy due to obesity”

- If BMI > 30 and the patient had myocardial ischemia, cerebrovascular, or respiratory disease then list obesity as a contributing condition (Sens and Hughes)

- If BMI > 30 and the patient died from trauma or drug toxicity, do NOT list obesity in the reporting

- Do NOT list obesity on the death certificate if the BMI is < 30

- A proposed definition for obesity related cardiomyopathy is cardiomegaly (>550 g in males and >450 g in females) in individuals with a BMI >30 kg/m2 with no history of hypertension or diabetes and no other cardiac disease such as CAD or valve disease at autopsy (Westaby 2023). The Westaby study found evidence that weight was the most reliable metric for distinguishing obesity-related cardiomyopathy from obesity-related increase in size without cardiomyopathy. Weight was more reliable than left ventricular wall thickness or left ventricular fibrosis.

Image: Cases of obesity cardiomyopathy (OCM) are significantly larger in weight than hearts from non-obese or obese individuals without cardiomyopathy. (Image credit: Westaby 2023).

Image: Cases of obesity cardiomyopathy (OCM) are significantly larger in weight than hearts from non-obese or obese individuals without cardiomyopathy. (Image credit: Westaby 2023).

- Macrosteatosis of the liver is graded as mild (<30%), moderate (30-60%), and severe (>60%)

Recommended References

- Sens M, Hughes R. Obesity. Expert Path (Login Required). Accessed August 2024.

- Gonçalves LB, Miot HA, Domingues MAC, Oliveira CC. Autopsy Patients With Obesity or Metabolic Syndrome as Basic Cause of Death: Are There Pathological Differences Between These Groups? Clin Med Insights Pathol. 2018 Jul 30;11:1179555718791575. doi: 10.1177/1179555718791575. PMID: 30083067; PMCID: PMC6066805.

Additional References

- Ghafoor M, Kamal M, Nadeem U, Husain AN. Educational Case: Myocardial Infarction: Histopathology and Timing of Changes. Acad Pathol. 2020 Dec 17;7:2374289520976639. doi: 10.1177/2374289520976639. PMID: 33415186; PMCID: PMC7750744.

- Goel V, et. al. Autopsy Findings and Cardiac Arrest Rhythms in Young Obese Patients With Sudden Cardiac Death of Uncertain Aetiology. Heart, Lung and Circulation, Volume 32, S189; 2023.

- King LK, March L, Anandacoomarasamy A. Obesity & osteoarthritis. Indian J Med Res. 2013;138(2):185-93. PMID: 24056594; PMCID: PMC3788203.

- Kleiner DE, Makhlouf HR. Histology of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis in Adults and Children. Clin Liver Dis. 2016 May;20(2):293-312. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2015.10.011. Epub 2015 Dec 28. PMID: 27063270; PMCID: PMC4829204.

- Michaud K, Basso C, d’Amati G, Giordano C, Kholová I, Preston SD, Rizzo S, Sabatasso S, Sheppard MN, Vink A, van der Wal AC; Association for European Cardiovascular Pathology (AECVP). Diagnosis of myocardial infarction at autopsy: AECVP reappraisal in the light of the current clinical classification. Virchows Arch. 2020 Feb;476(2):179-194. doi: 10.1007/s00428-019-02662-1. Epub 2019 Sep 14. PMID: 31522288; PMCID: PMC7028821.

- Panuganti KK, Nguyen M, Kshirsagar RK. Obesity. [Updated 2023 Aug 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459357/

- Sens M, Hughes R. Obesity. Expert Path (Login Required). Accessed August 2024

- Westaby, J, Dalle-Carbonare, C, Ster, I. et al. Obesity Cardiomyopathy in Sudden Cardiac Death: A Distinct Entity? A Comparative Study. JACC Adv. 2023 Jul, 2 (5) .