Authors: Samantha Wahlers & John Walsh MD*

Background

Diabetes mellitus (DM) encompasses metabolic diseases, type 1 and type 2, that have an underlying chronic hyperglycemia. In type 1 DM, the body’s immune system destroys 𝜷 pancreatic islet cells, which produce insulin. This autoimmune response results in an absolute insulin deficiency and presents in childhood. For a more in depth discussion on Type 1 diabetes see this article. In type 2 DM, the 𝜷 pancreatic islet cells are dysfunctional leading to impaired insulin secretion. This insulin deficiency is often due to obesity and sedentary habits (for more information see this article). As it pertains to autopsy, diabetes mellitus has become a major cause of death worldwide as well as a contributing factor to death, as associated with other conditions. Diabetic ketoacidosis is the most common cause of death in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes. In Type 2 diabetes, DKA remains the most common cause of death, but among cases called DKA, Hyperosmolar Hyperglycemia Syndrome (HHS) may be underreported or inaccurately reported. The mortality rate of DKA is estimate at about 1%, while the mortality rate of HHS is estimated as high as 20%.

Other etiologies of diabetes mellitus include

- Maturity Onset Diabetes of the Young (MODY) is caused by a genetic defect that leaves 𝜷 cells dysfunctional

- Gestational diabetes

- Glucocorticoid-induced diabetes

- Pancreatic pathologies

- Cystic fibrosis

- Pancreatitis

- Cushing disease

Diabetes affects multiple organ systems throughout the body. Below is a quick reference table of the major organ systems affected by DM

| Organ | Pathophysiology |

| Eyes | Diabetes can cause several eye problems, the most significant being diabetic retinopathy, which results from damage to the blood vessels in the retina. This can lead to vision impairment and blindness. Other complications include diabetic macular edema, cataracts, and glaucoma. |

| Cardiovascular system | Diabetes significantly increases the risk of cardiovascular diseases, including coronary artery disease, heart attacks, and heart failure. The combination of high blood glucose levels, hypertension, and dyslipidemia in diabetic patients accelerates the process of atherosclerosis, leading to narrowed and hardened arteries. |

| Liver | Diabetes increases the risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), which can progress to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), liver fibrosis, and cirrhosis. Insulin resistance plays a significant role in the accumulation of fat in liver cells. |

| Pancreas | Chronic hyperglycemia can lead to β-cell dysfunction and apoptosis, reducing insulin production and worsening hyperglycemia. This creates a vicious cycle that exacerbates diabetes and its complications. |

| Kidneys | Diabetic nephropathy is a major complication, characterized by progressive kidney damage leading to chronic kidney disease and potentially end-stage renal disease (ESRD). |

| Nerves | Diabetic neuropathy affects peripheral nerves, leading to symptoms such as pain, tingling, and numbness, particularly in the extremities. Autonomic neuropathy can affect the cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and genitourinary systems, leading to various functional impairments. |

| Skin | Uncontrolled diabetes can lead to various skin conditions, including bacterial and fungal infections, diabetic dermopathy, and necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum. Poor wound healing is also a common issue, often leading to chronic ulcers and infections. |

Advanced glycation end products (AGEs) are the underlying pathophysiology to most of these complications. The excess glucose in the blood covalently binds to plasma proteins, thereby altering the protein’s ability to function in receptor signaling pathways and enzymatic activities. In the setting of arteries, AGEs induce oxidative stress, thereby contributing to atherosclerosis.

Quick Tips at Time of Autopsy

Clinical History

- Should there be any concern for diabetes (DM) as the underlying cause of death, testing of vitreous fluid should be considered. While this ancillary test is discussed below, it is important to explore the possibility of a DM-related death prior to entering the autopsy suite, upon review of the patient’s history, so that the appropriate plan is in place to obtain vitreous or other diagnostic tissues

- Death, as a 1st presentation of diabetes, should be considered particularly in the extremes of age in the correct clinical circumstances such as: medical history of “seizure,” “convulsions,” “coma,” or altered mental status, weight loss, unquenchable thirst, “smelled funny” all should prompt consideration of diabetes in the differential and subsequent appropriate exam (including possible vitreous studies).

- Laboratory Diagnostic Criteria for DM

- Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) ≥ 6.5%

- Fasting plasma glucose ≥ 126 mg/dL

- 2-hour plasma glucose ≥ 200 mg/dL during oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT)

- Patient with classic symptoms of hyperglycemia or hyperglycemic crisis, random plasma glucose ≥ 200 mg/dL

- In absence of clear hyperglycemia, diagnosis requires 2 abnormal test results from same sample or 2 separate test samples

- Kidney function testing using urine analysis to look for microalbuminuria and ketonuria

- Blood work to detect antiglutamic acid decarboxylase antibodies

- For type 1 DM

- Antemortem physical exam findings for complications including

- Diabetic retinopathy

- Diabetic nephropathy

- Diabetic neuropathy

- Necrobiosis lipoidica

External Exam

- Body Habitus: obesity or marked weight loss could be indicators of Type 2 and Type 1 Diabetes, respectively.

- Infections: increased susceptibility to bacterial and fungal skin infections.

- Signs of Poor Circulation: peripheral edema, particularly in the legs and feet, with or without stasis dermatitis.

- Dermatopathic evidence of Peripheral Vascular Disease

- Skin tags: associated with insulin resistance and may be seen in pre-diabetics as well

- Diabetic Dermopathy: brownish patches on the skin, usually on the shins

- Acanthosis Nigricans: dark, velvety patches, often found in body folds and creases

- Necrobiosis Lipoidica: yellow, waxy areas on the skin, often on the lower legs

- Diabetic Foot Ulcers: open sores on the feet due to poor circulation and neuropathy.

- Poor wound healing: presence of chronic, non-healing wounds or scars indicating slow healing processes.

- Amputations: missing toes, feet, or lower limbs due to severe infections or gangrene secondary to diabetic complications.

- Neuropathy: deformities such as Charcot foot (joint dislocation and fractures in the foot) might be visible externally.

Images: (Left) Pigmented pretibial patches in a patient with diabetes known as diabetic dermopathy. (Right) Diabetic dermopathy on a darker skin complexion. (Image credits: (Left) Angelina Labib from Skin Manifestations of Diabetes Mellitus. (Right) Sam Gorelik from Science Direct).

Images: (Left) Pigmented pretibial patches in a patient with diabetes known as diabetic dermopathy. (Right) Diabetic dermopathy on a darker skin complexion. (Image credits: (Left) Angelina Labib from Skin Manifestations of Diabetes Mellitus. (Right) Sam Gorelik from Science Direct).

Images: (Left) Poorly demarcated hyperpigmented patches called acanthosis nigricans pictured on a lighter skin complexion. (Right) Acanthosis nigricans on a darker skin complexion. (Image credits: (Left) Scott Dulebohn from StatPearls. (Right) Shyam Verma from StatPearls).

Images: (Left) Poorly demarcated hyperpigmented patches called acanthosis nigricans pictured on a lighter skin complexion. (Right) Acanthosis nigricans on a darker skin complexion. (Image credits: (Left) Scott Dulebohn from StatPearls. (Right) Shyam Verma from StatPearls).

Image: Demarcated erythematous papules and plaques called necrobiosis lipoidica (Image credit: Angelina Labib from “Skin Manifestations of Diabetes Mellitus”).

Image: Demarcated erythematous papules and plaques called necrobiosis lipoidica (Image credit: Angelina Labib from “Skin Manifestations of Diabetes Mellitus”).

Image: Rocker bottom deformity called charcot foot in a patient with diabetes mellitus (Image Credit: Lee Rogers from “The Charcot Foot in Diabetes”)

Image: Rocker bottom deformity called charcot foot in a patient with diabetes mellitus (Image Credit: Lee Rogers from “The Charcot Foot in Diabetes”)

Ancillary Testing

- Testing of vitreous electrolytes should be considered in deaths without immediately evident cause of death [found down, or found dead in bed], or where a traumatic cause of death may have been predisposed by a natural event [motor vehicle collision]. While many of these scenarios will be forensic cases, they can present in hospital cases as well.

- Collecting vitreous

- This can be done even when decomposition is present.

- Collection goals: minimum of 1mL of clear translucent vitreous fluid.

- Fluid can be aggregated into 1 Red top tube (R & L eye together) or, if sufficient fluid or if fluid from 1 eye is cloudy, collected R eye / L left eye.

- If gray top tubes are used, the quantitative results for sodium and/or potassium will be affected.

- Storage: short term storage in a refrigerator is sufficient, but long term storage requires freezing at -700F

- Multiple serum markers may also be useful

- Glycated hemoglobin (use a lavender top tube)

- Serum beta-hydroxybutyrate (use a red or gold top tube)

- Serum isopropyl alcohol (use a gray top tube)

- Serum C reactive protein (use a red or gold top tube)

- Urine glucose

- CBC: may indicate stress reaction and / or evidence of infection. Recent infection has been identified as a predisposing risk factor for HHS.

- While not done routinely in autopsy, it is possible to undertake advanced testing if indicated

- Immunofluorescence demonstrates linear IgG & albumin on glomerular basement membrane in the kidney.

- Electron Microscopy demonstrates thickening of glomerular basement membrane (> 600 nm thick) and/or lucent foci on the periphery of mesangial sclerosis.

- Immunohistochemistry

- WT-1 stain for podocytopenia

- Decreased amount of Beta and Alpha cells in the pancreas

Internal Examination

- Arteries: the vascular consequences of diabetes are generally grouped into microvascular and macrovascular. Microvascular disease results in pathologies such as diabetic retinopathy, diabetic nephropathy, and diabetic neuropathy – detailed individually by organ system below. Macrovascular complications of diabetes include atherosclerosis which can result in complications such as stroke, myocardial infarction, and peripheral artery/vascular disease.

- Pancreas: progressive changes in DM1 and DM2 lead to a small pancreas (DM1 > DM2). Atrophy of the pancreatic tissue is more associated with DM1 due to autoimmune destruction of β-cells. In contrast, loss of mass is associated with fibrosis and lipomatosis in DM2 as a result of chronic hyperglycemia and associated metabolic stresses. In DM2 this can give the contour of the pancreas a serrated appearance.

- Kidneys: in the early stages of diabetes, kidneys may be enlarged due to hyperfiltration and hypertrophy of the nephrons as they try to compensate for increased glucose load. This is often more pronounced in the early stages of DM1. Over time, as diabetic nephropathy progresses, kidneys can become smaller due to the loss of functional renal tissue and the development of fibrosis. The surface of the kidneys may appear granular or nodular in advanced stages due to the presence of glomerulosclerosis and interstitial fibrosis. This granular appearance is not specific and can also be seen with hypertension and other causes of nephrosclerosis. Of note, DM lesions are not uniform between individuals or even within the same individual.

Image: A bisected kidney with cortical granularity and pitting suggestive of underlying glomerulosclerosis. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

Image: A bisected kidney with cortical granularity and pitting suggestive of underlying glomerulosclerosis. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

- Liver: changes in the liver happen as a consequence of both direct effects from diabetes as well as secondarily from associated hyperlipidemia, these include hepatomegaly, hepatosteatosis, and, in advanced cases, fibrosis and cirrhosis.

Quick Tips at Time of Histology Evaluation

Pancreas

- Type I DM: early disease is marked by irregularly shaped islet cells and lymphocyte infiltration. Later disease is marked by interlobular and interacinar fibrosis and exocrine atrophy.

- Type II DM: perilobular and intraacinar fibrosis, a reduced number of regularly shaped islets, and amyloidosis (evaluate with a congo red stain).

Image: This section from the pancreas of a patient with diabetes (DM2) shows fat deposition and fibrosis. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/Stanford University).

Image: This section from the pancreas of a patient with diabetes (DM2) shows fat deposition and fibrosis. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/Stanford University).

Image: In the same patient as above, there is increased fibrosis (black arrow), and amyloid deposition (red) with congo red stain shown in the inset. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/Stanford University).

Image: In the same patient as above, there is increased fibrosis (black arrow), and amyloid deposition (red) with congo red stain shown in the inset. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/Stanford University).

Image: Hyaline arteriolosclerosis can be seen in many organs including spleen (shown here), but also eyes, kidney, etc. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/Stanford University).

Image: Hyaline arteriolosclerosis can be seen in many organs including spleen (shown here), but also eyes, kidney, etc. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/Stanford University).

Kidney

- The key histologic finding in diabetic nephropathy will be prominent arterial hyalinosis (note, in DM this will be present in the afferent and efferent arterioles, unlike in hypertension which is only see in the afferent arteriole)

Image: Hyaline arteriolosclerosis can be seen in many organs and is classically identified in the kidney. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/Stanford University).

Image: Hyaline arteriolosclerosis can be seen in many organs and is classically identified in the kidney. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/Stanford University).

- Kimmelstiel-Wilson nodules and mesangial sclerosis (supported by PAS and/or Jones methenamine silver stains); acellular lesions with a hyaline like core, which may indicate long-standing diabetes. Hypercellular mesangial proliferation may also be seen.

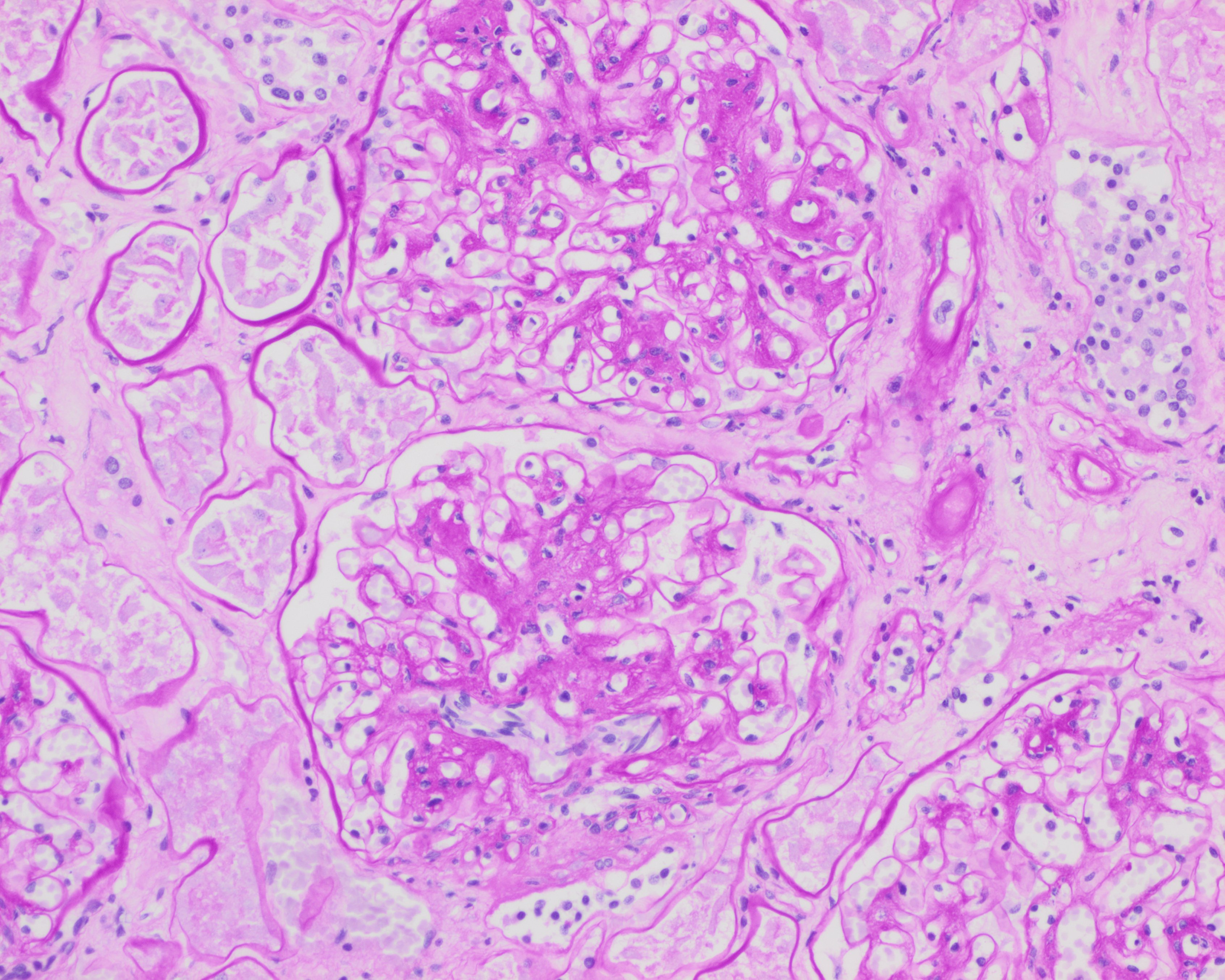

Image: Kimmelstein-Wilson nodule in a glomerulus, PAS staining. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

Image: Kimmelstein-Wilson nodule in a glomerulus, PAS staining. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

Image: Mesangial expansion in a glomerulus, H&E staining. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington)

Image: Mesangial expansion in a glomerulus, H&E staining. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington)

Image: Mesangial expansion in glomeruli, PAS staining. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington)

Image: Mesangial expansion in glomeruli, PAS staining. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington)

- In patients who clinically had severe proteinuria, tubules may show lipid droplets.

- Inflammation will often be sparse, however there may be an increase in interstitial eosinophils.

- Advanced disease includes tubular atrophy, interstitial fibrosis, and globally sclerosed glomeruli

- Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis can also be seen in DM. (FSGS is the most common primary cause of nephrotic syndrome in the adult population and diabetes is the most common secondary cause in adults).

Image: Globally sclerosed glomerulus (top of the image) and a segmentally sclerosed glomerulus (middle of the image) and a non-sclerosed glomerulus with mesangial expansion (bottom of the image) all present in one high power field in a patient with DM on H&E. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

Image: Globally sclerosed glomerulus (top of the image) and a segmentally sclerosed glomerulus (middle of the image) and a non-sclerosed glomerulus with mesangial expansion (bottom of the image) all present in one high power field in a patient with DM on H&E. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

- Immunofluorescence demonstrates linear IgG and albumin in the basement membrane

- Electron microscopy demonstrates basement membrane thickening

- Patients with diabetic Ketoacidosis may demonstrate proximal convoluted tubules with subnuclear glycogen filled vacuoles (Armanni-Ebstein lesion)

- In a study by Perrone et al., medical renal diseases were classified, including diabetic nephropathy, and analyzed to see if they were noticed at the time of autopsy. They found that these diagnoses were not reported in 60% of cases during the initial autopsy evaluation. Henriksen points out that, “Since kidney biopsy is usually avoided in critically ill patients, histologic evaluation of autopsy kidneys may be the first and only opportunity to identify these diseases. This is crucial as these findings may have implications for the surviving family members, particularly for those diseases with a genetic component.” These two studies highlight the need for high quality autopsy investigation in diabetic patients.

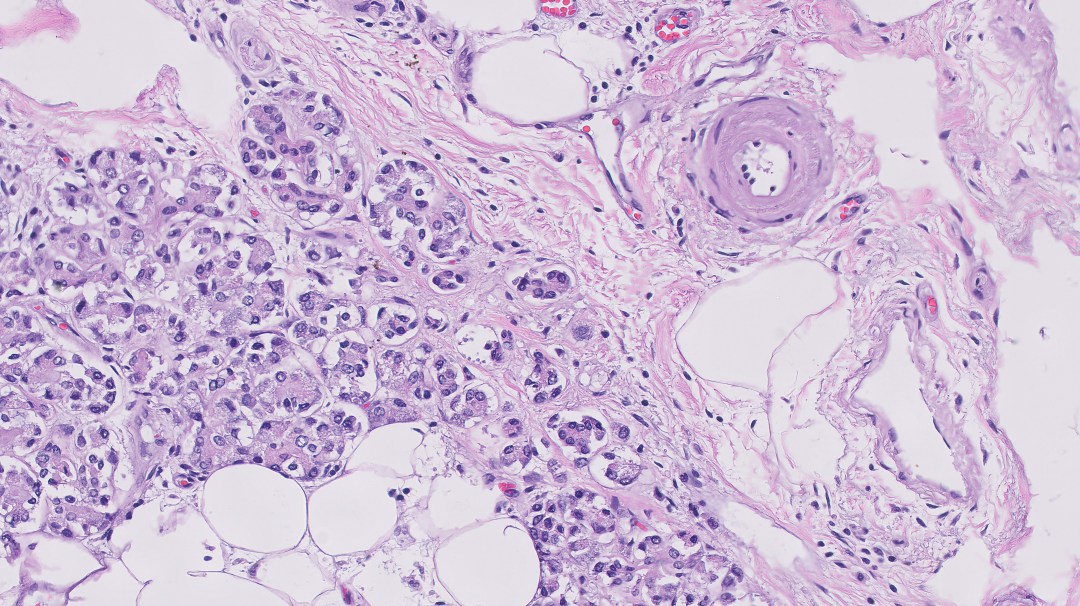

Image: Proximal convoluted tubules with subnuclear glycogen filled vacuoles demonstrating an Armanni-Ebstein lesion. (Image credit: Parai Milroy from Academic Forensic Pathology).

Image: Proximal convoluted tubules with subnuclear glycogen filled vacuoles demonstrating an Armanni-Ebstein lesion. (Image credit: Parai Milroy from Academic Forensic Pathology).

Cardiovascular

- Atherosclerosis

- Sequelae of hypertension, a common comorbidity in DM

Liver

- Glyocgenic hepatopathy can be seen in patients with poorly controlled Type I DM

Image: Glycogenic hepatopathy. (Image credit: Maria Westerhoff, ExpertPath).

Image: Glycogenic hepatopathy. (Image credit: Maria Westerhoff, ExpertPath).

Quick Tips at Time of Reporting

Cause of death statements

- Example causes of death related to diabetes

- Phrases like “in the setting of,” “in conjunction with” can be utilized when there are multiple events occurring.

- Acute Myocardial Infarction in the setting of…

- Multilobar pneumonia in conjunction with…

- Part II – Other significant contributing conditions – Diabetes should be included when appropriate – heart disease, obesity, etc

Interpretation of ancillary testing

| DKA | HHS | |

| Vitreous Electrolytes | WNL | Elevated Na+ secondary to dehydration |

| Glucose | >200 | >600 |

| Ketones | + | negative |

| B-Hydroxybutyrate | Positive | Negative |

- Vitreous Humor Analysis

- A vitreous glucose over 200 mg/dL is supportive of diabetes.

- A vitreous glucose over 200 mg/dL in combination with ketoacids (beta-hydroxybutyrate and acetoacetate) is supportive of a diagnosis of diabetic ketoacidosis. pH will be consistent with metabolic acidosis.

- Serum beta-hydroxybutyrate analysis

- Beta-hydroxybutyrate seems to be a better postmortem indicator of ketoacidosis than acetone (Palmiere 2015).

- Decompositional changes are not associated with beta-hydroxybutyrate production and blood beta-hydroxybutyrate levels in decomposed bodies can be considered an appropriate biochemical parameter in the estimation of beta-hydroxybutyrate concentrations at the time of death (Palmiere 2015).

- Ranges proposed by Iten and Meier:

- up to 500 µmol/L (corresponding to 5.2 mg/dL) ⇒ normal

- 500 to 2500 µmol/L (corresponding to 26 mg/dL) ⇒ increased

- over 2500 µmol/L ⇒ pathological

- Serum isopropyl alcohol is a marker of ketoacidosis and a product of acetone metabolism in clinical conditions presenting with increased ketone levels.

- Serum C reactive protein is stable after death and is often increased in cases of ketoacidosis.

- Urine glucose should not be the only marker to posit a cause of death but rather can be used to confirm findings obtained from vitreous glucose and blood ketone body measurements.

Histology evaluation

- The Renal Pathology Society has classification criteria for diabetic nephropathy which can be integrated into the diagnostic line of the final autopsy report.

| Class I | GBM thickening on electron microscopy; minimal, non-specific, or no changes on light microscopy |

| Class II | Increase in mesangial matrix |

| Class IIa | Mesangial expansion <25% |

| Class IIb | Mesangial expansion >25% |

| Class III | Nodular glomerulosclerosis; Kimmelstiel-Wilson nodules |

| Class IV | Advanced glomerulosclerosis; >50% glomeruli are sclerotic |

(Table adapted from: Pathogenesis of Diabetic Nephropathy, Chronic Kidney Disease and Type 2 Diabetes)

- Of note, diabetes is a significant risk factor for neurodegenerative disease; neurodegenerative work up for older adults may be considered and/or indicated

Image: Progression of atherosclerotic calcification in diabetic foot patients. (Top row) In gross observation, different degrees of gangrene, swelling, skin ulcers, and infection in diabetic foot patients among the three groups were observed. (Middle and bottom rows) Representative photomicrographs of atherosclerotic lesions in anterior tibial artery cross-sections after H&E staining (×40) and von Kossa staining (black calcium particles) (×200). (Image Credit: Wang 2016).

Image: Progression of atherosclerotic calcification in diabetic foot patients. (Top row) In gross observation, different degrees of gangrene, swelling, skin ulcers, and infection in diabetic foot patients among the three groups were observed. (Middle and bottom rows) Representative photomicrographs of atherosclerotic lesions in anterior tibial artery cross-sections after H&E staining (×40) and von Kossa staining (black calcium particles) (×200). (Image Credit: Wang 2016).

- Of note, diabetic heart disease is a distinct pathology independent of comorbidities such as coronary artery disease, hypertension, and obesity. However, in practice, these etiologies can be challenging to distinguish at autopsy. One proposed definition requires autopsy and clinical data for correlation.

- The pathological changes in early DC include cardiac hypertrophy, fibrosis and microvascular disease (intimal thickening, smooth muscle proliferation, and perivascular fibrosis in arterioles).

- The diagnostic criteria for DC (Tarquini et al): Presence of DM, exclusion of coronary artery disease, valvular or congenital heart disease, exclusion of hypertensive heart disease, exclusion of viral myocarditis and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) <50%, left ventricular end-diastolic volume index (LVEDVI) >97 ml/m2.

Recommended References

- Butnor KJ, Proia AD. Unexpected autopsy findings arising from postmortem ocular examination. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001 Sep;125(9):1193-6. doi: 10.5858/2001-125-1193-UAFAFP. PMID: 11520270.

- Hockenhull J, Dhillo W, Andrews R, Paterson S. Investigation of markers to indicate and distinguish death due to alcoholic ketoacidosis, diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state using post-mortem samples. Forensic Sci Int. 2012 Jan 10;214(1-3):142-7. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2011.07.040. Epub 2011 Aug 12. PMID: 21840144.

- Kambham N, Roberts I. Diabetic Nephropathy. Expert Path (Login Required). Accessed August 2024.

- Lamps L. Diabetes Mellitus. Expert Path (Login Required). Accessed August 2024.

- Palmiere C. Postmortem diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Croat Med J. 2015 Jun;56(3):181-93. doi: 10.3325/cmj.2015.56.181. PMID: 26088843; PMCID: PMC4500977.

- Singh KB, Nnadozie MC, Abdal M, Shrestha N, Abe RAM, Masroor A, Khorochkov A, Prieto J, Mohammed L. Type 2 Diabetes and Causes of Sudden Cardiac Death: A Systematic Review. Cureus. 2021 Sep 20;13(9):e18145. doi: 10.7759/cureus.18145. PMID: 34692349; PMCID: PMC8525691.

Additional References

- Adeyinka A, Kondamudi NP. Hyperosmolar Hyperglycemic Syndrome. [Updated 2023 Aug 12]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482142/

- Henriksen KJ. Autopsy kidneys: an overlooked resource. Autops Case Rep. 2018 Mar 2;8(1):e2018013. doi: 10.4322/acr.2018.013. PMID: 29588908; PMCID: PMC5861983.

- Iten PX, Meier M. Beta-hydroxybutyric acid–an indicator for an alcoholic ketoacidosis as cause of death in deceased alcohol abusers. J Forensic Sci. 2000;45:624–32.

- Perrone ME, Chang A, Henriksen KJ. Medical renal diseases are frequent but often unrecognized in adult autopsies. Mod Pathol. 2018 Feb;31(2):365-373. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2017.122. Epub 2017 Oct 6. PMID: 28984299.

- Rose KL, Collins KA. Vitreous postmortem chemical analysis. NewsPath [serial online]. December 2008;1-3. College of American Pathologists. Available at http://bit.ly/f2t2FL. Accessed: June 7, 2010.

- Singh VP, Bali A, Singh N, Jaggi AS. Advanced glycation end products and diabetic complications. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2014 Feb;18(1):1-14. doi: 10.4196/kjpp.2014.18.1.1. Epub 2014 Feb 13. PMID: 24634591; PMCID: PMC3951818.

- Sreng S, Maneerat N, K. Y. Win, K. Hamamoto and R. Panjaphongse, “Classification of Cotton Wool Spots Using Principal Components Analysis and Support Vector Machine,” 2018 11th Biomedical Engineering International Conference (BMEiCON), Chiang Mai, Thailand, 2018, pp. 1-5, doi: 10.1109/BMEiCON.2018.8609962.

- Tarquini R, Pala L, Brancati S, Vannini G, De Cosmo S, Mazzoccoli G, Rotella CM. Clinical Approach to Diabetic Cardiomyopathy: A Review of Human Studies. Curr Med Chem. 2018;25(13):1510-1524. doi: 10.2174/0929867324666170705111356. PMID: 28685679.

- Yamagishi SI, Matsui T. Role of Hyperglycemia-Induced Advanced Glycation End Product (AGE) Accumulation in Atherosclerosis. Ann Vasc Dis. 2018 Sep 25;11(3):253-258. doi: 10.3400/avd.ra.18-00070. PMID: 30402172; PMCID: PMC6200622.

- Wang, Zhongqun & Li, Lihua & Du, Rui & Yan, Jinchuan & Yuan, Wei & Jiang, Yicheng & Xu, Suining & Ye, Fei & Yuan, Guoyue & Zhang, Baohai & Liu, Peijing. (2016). CML/RAGE signal induces calcification cascade in diabetes. Diabetology & Metabolic Syndrome. 8. 83. 10.1186/s13098-016-0196-7.

*The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Navy, Naval Construction Group (NSG), Uniformed Services University of Health Science, Defense Health Agency, U.S. Navy Bureau of Medicine and Surgery, Department of Defense, or the US Government. The authors report no conflict of interest or sources of funding.