Authors: Aleks Penev MD PhD & Desiree Marshall MD

Background

Stroke is a common term to refer to the clinical findings in a patient who has suffered an acute cerebral infarct. Cerebral infarction denotes an area of tissue necrosis in the brain localized to a particular vascular territory. This necrosis is secondary to insufficient oxygenation due to compromised blood flow. This can occur in

- arterial occlusion

- severe reduction in arterial flow in the absence of complete occlusion

- vascular stasis secondary to impaired venous outflow (often called a “venous infarct”)

Vascular occlusion is caused by either a thrombus – a build-up of material (often fibrin and platelets) on top of a damaged portion of the vessel – or an embolus, which denotes a detached portion of material that becomes lodged in a vessel with a caliber smaller than the diameter of the tissue fragment.

While occasionally used interchangeably, pure hypoxia, ischemia, and vaso-occlusive ischemia should be distinguished:

- Hypoxia – lack of oxygen but not necessarily a lack of perfusion. The brain can adapt to pure hypoxia when it happens chronically over time (such as with a progressive lung disease). Carbon monoxide poisoning is an example of an acute, pure hypoxia.

- Ischemia – hypoxia due to decreased perfusion. It includes a tissue’s response to decreased oxygenation such as the production of damaging metabolites (//lactic acid). In cases of vaso-occlusive ischemia, it also includes decreased nutrient delivery and waste removal (such as lack of glucose delivery and buildup of cytotoxic glutamate from damaged neurons).

Of note, free radicals, lactic acid, cerebral edema, and inflammation cannot develop in unperfused, completely ischemic tissue. They develop following reperfusion (or in the ischemic penumbra surrounding an infarct where there is sublethal ischemia). For more information on these distinctions, see the first 15 minutes of this lecture by Dr. Dimitri Agamanolis.

Acute ischemia that is localized to a vascular territory is covered here as stroke. Global hypoxemia, such as from cardiac arrest, hypotension, increased intracranial pressure, etc. is covered under hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. (Notably, one specific end point of these processes is covered under brain death).

Quick Tips at Time of Autopsy

Clinical History

- Stroke due to thrombosis is often secondary to atherosclerosis and arteriosclerosis, which are associated with systemic hypertension, diabetes mellitus, tobacco smoking, hyperlipidemia, and obesity.

- Prior stroke is a significant risk for stroke recurrence.

- Medications can be clues to the presence of underlying atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, prior strokes or their risk factors (e.g. statins, antiplatelet agents, anti-hypertensive drugs, or anti-diabetic medications).

- Additional etiologies for stroke include

- Vascular abnormalities (e.g. arteriovenous malformations)

- Inflammatory causes (vasculitides, sarcoidosis, etc)

- Hypercoagulability (hereditary, paraneoplastic, medications),

- Drug use (particularly stimulants like cocaine, methamphetamine, phencyclidine)

- Infectious (septic emboli, angioinvasive fungus, HSV, infectious vasculitides)

- Tumors (both primary and metastatic)

- Head trauma (arterial dissection, etc)

- Correlation with clinical imaging is useful to localize lesions and determine the vascular territory involved.

- Symptoms documented in the patient records can also help localize the affected area.

- Lacunar Infarcts are small infarcts that affect deeper cerebral structures like the basal ganglia, thalamus and white matter due to occlusion and small vessel disease in the small penetrating arteries that supply these areas. They are most commonly associated with diabetes, hypertension and amyloid.

External examination

- External signs of acute stroke are limited – many acute asymmetries in muscle tone will not persist post-mortem. However, asymmetric muscle atrophy from a remote stroke may be observable.

- Long-term immobilization due to prior strokes can result in decubitus ulcers.

- Examine the body for evidence of trauma, notably bruises and fractures, as well as signs of head injury including scalp hematomas and basilar skull fractures (periorbital bruising a.k.a. “racoon eyes”, or blood in the ears) which may be present if that patient fell at the time of their stroke.

- Evidence of chronic stimulant use (track marks in intravenous drug use, poor dentition in methamphetamine use, nasal septal damage in chronic cocaine use) can sometimes be identified in drug-related infarcts (such as from bacterial emboli from endocarditis).

Internal examination

Embolic strokes come from three major sources. They should be carefully explored in order to find the source of acute embolic infarcts.

- Heart (mural thrombus) – due to atrial fibrillation, dyskinesis secondary to infarct, or endocarditis – also, rarely cardiac myxoma

- Tissue (often traumatic) – marrow elements from long bones, amniotic fluid embolus

- Arterial plaques – often secondary to ruptured carotid artery atherosclerosis releasing plaque material (vs. vessel wall causing thrombosis).

- Examination of the heart, aorta, coronary and renal arteries and kidneys is important to describe possible atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

- Risk for a mural thrombus is increased in patients with central venous catheters, cardiac pathology (including a myocardial infarction which can decrease wall motion leading to blood stasis and subsequent thrombus), etc.

- Examine cardiac valves for vegetations.

- Examine for the presence of a patent foramen ovale, which can permit venous thrombi (ie, deep vein thrombi due to immobility or contraceptives) from the systemic circulation access to the left sided circulation.

- Document the presence and correct placement of a Watchman device (or other DVT prophylaxis device) in the atrial appendage.

Image: proper placement of a Watchman device which is designed to keep the atrial appendage open, encouraging blood flow and decreasing the risk for thrombus. The distal end of the Watchman device should terminate in the inferior vena cava and can be another site of thrombus formation due to non-laminar blood flow. (Image credit: The Heart Rhythm Institute of Arizona).

Image: proper placement of a Watchman device which is designed to keep the atrial appendage open, encouraging blood flow and decreasing the risk for thrombus. The distal end of the Watchman device should terminate in the inferior vena cava and can be another site of thrombus formation due to non-laminar blood flow. (Image credit: The Heart Rhythm Institute of Arizona).

On examination of the brain, pay particular attention to evidence of atherosclerosis in the Circle of Willis and look for any areas of gross atherosclerosis or obstruction, as well as other lesions such as aneurysm, vascular malformations or masses.

- Serial cross sections of the Circle of Willis can be useful to document the presence/absence of occlusive lesions.

Image: (Left) Removed Circle of Willis and surrounding vasculature with arrow at the basilar artery for orientation. (Right) Schematic of Circle of Willis with most frequent locations of obstructive lesions and arrow at the basilar artery. (Image credit: (Left) Meagan Chambers/University of Washington. (Right) E&P’s Manual of Basic Neuropath, Chapter 4, pg 95.)

Image: (Left) Removed Circle of Willis and surrounding vasculature with arrow at the basilar artery for orientation. (Right) Schematic of Circle of Willis with most frequent locations of obstructive lesions and arrow at the basilar artery. (Image credit: (Left) Meagan Chambers/University of Washington. (Right) E&P’s Manual of Basic Neuropath, Chapter 4, pg 95.)

Image: Cerebral vascular territories. Localized findings in a vessel, such as a ruptured atherosclerotic plaque, can be correlated with downstream ischemic changes. (Image credit: Ophiuchus).

Image: Cerebral vascular territories. Localized findings in a vessel, such as a ruptured atherosclerotic plaque, can be correlated with downstream ischemic changes. (Image credit: Ophiuchus).

- Assess cortical surface and cut sections for evidence of ischemic damage, particularly looking for areas of asymmetry, with a variable appearance based on the chronicity of the stroke, as follows.

| Time | Gross Changes Associated with Ischemia/Infarction |

| 0-6 hours | No visible alteration |

| 8-48 hours | Edematous swelling and softening of tissue, discoloration, loss of gray-white distinction with indistinct lesional borders, occasional vascular congestion (especially in cortex) |

| 2-10 days | Persistent swelling, tissue becomes friable, boundaries better defined |

| >3 weeks | Cavitation – necrotic tissue gradually replaced

by sunken yellow-gray tissue |

| >2-3 months | Injured tissue replaced by cystic scarring lined by leptomeninges with intersecting vascular connective tissue |

(Adapted from: Gray 2019)

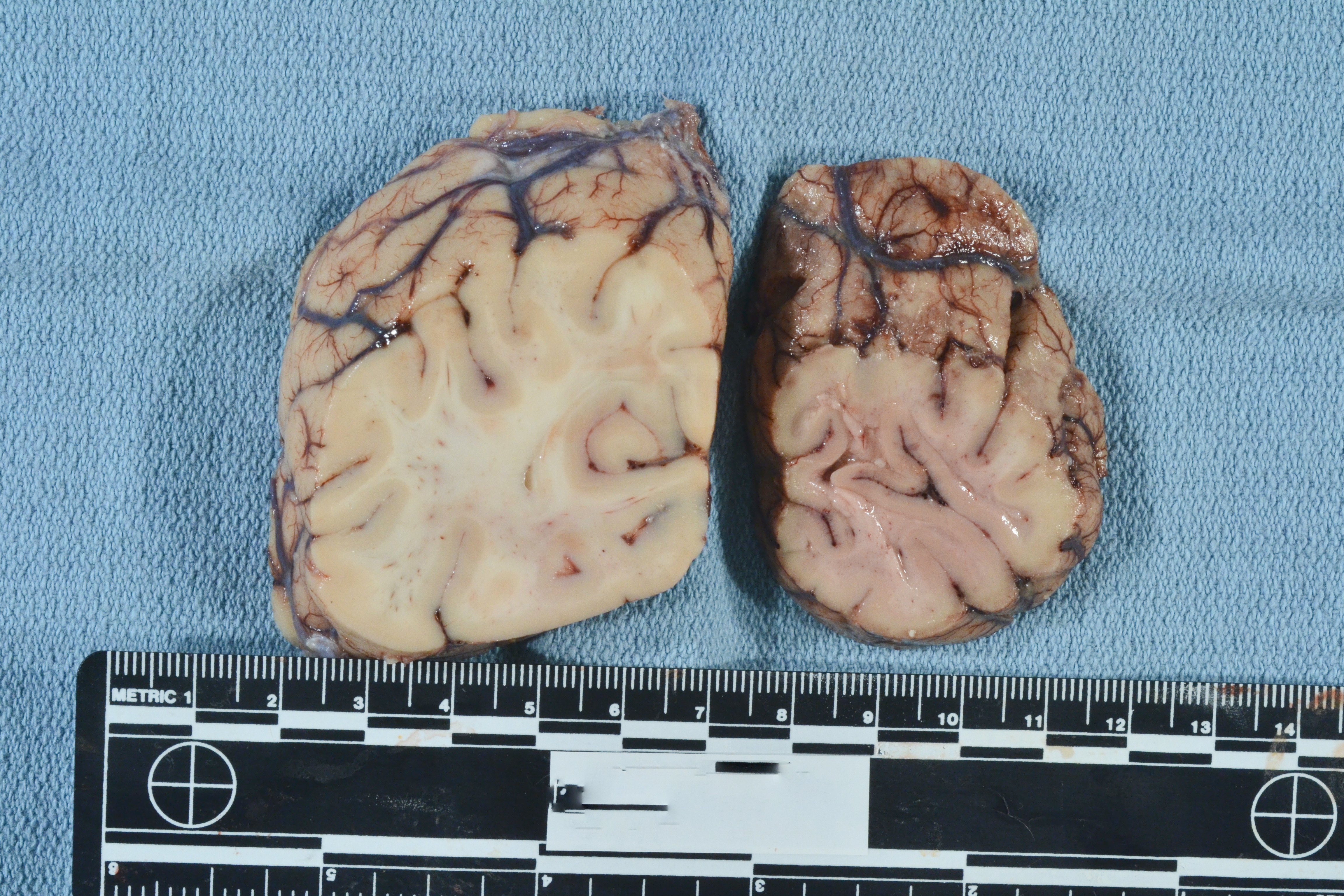

Image: This patient experienced an acute right-sided posterior cerebral artery stroke. The occipital lobe section on the left is the unaffected side with tan-white coloration and a clear gray-white junction. The affected lobe on the right has diffuse dusky discoloration and blurring of the gray-white junction. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

Image: This patient experienced an acute right-sided posterior cerebral artery stroke. The occipital lobe section on the left is the unaffected side with tan-white coloration and a clear gray-white junction. The affected lobe on the right has diffuse dusky discoloration and blurring of the gray-white junction. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

Image: Example of a cavitary lesion/chronic infarct in the frontal white matter sparing the cortex and with yellow/golden discoloration from hemosiderin. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

Image: Example of a cavitary lesion/chronic infarct in the frontal white matter sparing the cortex and with yellow/golden discoloration from hemosiderin. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

- When sampling potentially ischemic tissue, orient sections to capture the transition from normal brain to injured tissue (see histology images below for examples).

- Infarcts with reperfusion can be red in color due to extravasated RBCs

- Acute Hemorrhage- red-brown, mass forming with possible mass effect on surrounding brain

- Chronic Hemorrhage – cavitation with orange-yellow rim

- Lacunar infarcts can have significant clinical symptoms without significant edema/herniation, so important to consider when no large cortical lesions can be identified. They can be bilateral.

- Localized lesions have an ischemic penumbra characterized by sublethal tissue damage. In these areas there is frequently breakdown of the blood brain barrier. In patients with hyperbilirubinemia, there can be green discoloration from bilirubin staining of these leaky tissues.

Image: A right frontal bleed in a patient with hyperbilirubinemia demonstrates bright green discoloration in adjacent tissues from bilirubin staining in areas with breakdown of the blood-brain barrier. (Image credit: Desiree Marshall/University of Washington).

Image: A right frontal bleed in a patient with hyperbilirubinemia demonstrates bright green discoloration in adjacent tissues from bilirubin staining in areas with breakdown of the blood-brain barrier. (Image credit: Desiree Marshall/University of Washington).

Quick Tips at Time of Histology Evaluation

Microscopic changes of cerebral ischemia will appear following transient or persistent obstruction, with changes becoming easily detectable at 6-12 hours and following the timeline below

| Time | Histologic Changes Associated with Ischemia/Infarction |

| 6 – 12 hours | acute neuronal ischemic changes (shrunken nucleus with nucleolar loss, eosinophilic cytoplasm and dispersed Nissl substance), endothelial swelling with edema, extravasated RBCs |

| 24 – 48 hours (“acute”) | evidence of margination/migration of neutrophils into injured area |

| 2 – 10 days (“evolving”) | Neutrophils replaced by lipid-laden “foamy” macrophages, predominantly clustering around vessels, increased proliferation of vessels following day 5, reactive gliosis. At day 7-10 retraction bulbs/axonal spheroids are visible on H&E. |

| >10 days (“subacute”) | Microscopic liquefaction, macrophage proliferation ebbs and increased swollen, reactive (= gemistocytic) astrocytes (generally, reactive gliosis takes about two weeks to develop). |

| Months (‘chronic”) | Cystic space lined by increased gliosis, some macrophages present around small, thin-walled vessels in remnant strands of connective tissue |

(Adapted from: Gray 2019)

- It is important to note that the histologic timeline does not always match the clinical/symptomatic timeline.

- Additionally, the categories of acute/subacute/chronic are not firm and these should be taken as rough guidelines. In general, subacute lesions should have densely packed sheets of lipid-laden macrophages (actively “cleaning up” myelin). Chronic lesions can retain some scattered macrophages (commonly hemosiderin laden macrophages) for years.

- Features of a stroke vs. global hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy can be overlapping; red-dead neurons, laminar necrosis, and other features may be seen in both. (Review the linked Autopsy Book article for additional information).

Image: Axonal spheroids (arrows). (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

Image: Axonal spheroids (arrows). (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

- APP (amyloid precursor protein) will highlight acute axonal injury (ischemic, traumatic, or other) within 3 hours of the event. It highlights axonal swellings/fragmentation and therefore will only highlight acute axonal injury in the white matter (it will not highlight injury to the cortex). It will not positively stain chronic infarcts. It can therefore be useful for the confirmation of acute injury when the early histologic findings are subtle or equivocal. If APP is not available, some of the IHC stains for amyloid-beta (such as 6E10) will cross react and also demonstrate positive staining in acute axonal injury.

Image: The panel on the left demonstrates a well demarcated area of pallor in the white matter consistent with an infarct (area between the arrows). In the center panel, at higher power, there is a relatively clear border between the ischemic tissue (left side of the image) and the non-ischemic tissue (right side of the image) which is emphasized by a black dividing line; on the left there is increased vacuolization compared to the right. Additionally, consistent with an acute lesion, there are no macrophages yet. The panel on the right demonstrates positive APP staining which supports the histologic findings of an acute infarct. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

Image: The panel on the left demonstrates a well demarcated area of pallor in the white matter consistent with an infarct (area between the arrows). In the center panel, at higher power, there is a relatively clear border between the ischemic tissue (left side of the image) and the non-ischemic tissue (right side of the image) which is emphasized by a black dividing line; on the left there is increased vacuolization compared to the right. Additionally, consistent with an acute lesion, there are no macrophages yet. The panel on the right demonstrates positive APP staining which supports the histologic findings of an acute infarct. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

Image: In this acute infarct, marginating neutrophils accumulate at the interface of the leptomeninges and the brain parenchyma. Unlike sites outside of the CNS, neutrophils do not linger for long and these will quickly be replaced by macrophages. Therefore, seeing them suggests a relatively small time window (~24-48 hours). (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

Image: In this acute infarct, marginating neutrophils accumulate at the interface of the leptomeninges and the brain parenchyma. Unlike sites outside of the CNS, neutrophils do not linger for long and these will quickly be replaced by macrophages. Therefore, seeing them suggests a relatively small time window (~24-48 hours). (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

Image: In an area adjacent to an infarct; the cells are viable and there are no inflammatory infiltrates but the background has disrupted neuropil and reactive gemistocytic astrocytes (arrows). (Image source: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

Image: In an area adjacent to an infarct; the cells are viable and there are no inflammatory infiltrates but the background has disrupted neuropil and reactive gemistocytic astrocytes (arrows). (Image source: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

Image: from low power, the main clue to an infarct is often pallor. Closer examination should reveal cell drop out with or without inflammatory cells. (Image source: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

Image: from low power, the main clue to an infarct is often pallor. Closer examination should reveal cell drop out with or without inflammatory cells. (Image source: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

Image: this ischemic lesion is full of sheets of foamy macrophages and reactive vessels, consistent with a subacute infarct. Intact brain parenchyma is seen mostly at the lower left and upper right corners where reactive astrocytes are also present. (Image source: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

Image: this ischemic lesion is full of sheets of foamy macrophages and reactive vessels, consistent with a subacute infarct. Intact brain parenchyma is seen mostly at the lower left and upper right corners where reactive astrocytes are also present. (Image source: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

Image: Within a sulcus, the most superficial cortex is preserved thanks to collateral perfusion from the leptomeninges while the deeper cortex is ischemic and dead. (Image source: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

Image: Within a sulcus, the most superficial cortex is preserved thanks to collateral perfusion from the leptomeninges while the deeper cortex is ischemic and dead. (Image source: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

- Microscopic findings of other, specific etiologies for strokes may also be present including vasculitis, vascular malformations, vascular tumors (e.g. cavernomas), amyloid angiopathy, arterial dissection, etc.

Quick Tips at Time of Reporting

- Whether multiple lesions are from the same time period or different time periods is important to distinguish in the report. For example, an acute, lethal atherosclerotic occlusion of the middle cerebral artery may be the cause of death, but reporting additional smaller chronic infarcts supports the chronic nature of the patient’s atherosclerotic disease. Alternatively, in a younger patient with a history of endocarditis, lesions across different time periods may suggest a longer time course for his endocarditis than previously clinically suspected.

- Similarly, the size of the vessel (e.g. a macroscopic lesion vs. microscopic lesion) and the location (lacunar vs. territorial) are also important components of the patient’s clinical-pathologic correlation and should be clearly distinguished in the diagnostic line(s) of the report.

- If possible, report site, type (thrombus vs embolus) and severity of stenosis for any vaso-occlusive lesion

- A vascular stenosis of 75% or more is considered as critical

- Mechanism is an important consideration when characterizing cause of death, as even a remote stroke that causes functional deficits can contribute to death later on

- Large hemorrhages and infarcts (such as those caused by proximal occlusions or by significant involvement of deep structures) can acutely cause death due to increased intracranial pressure and herniation

- Significant associated subarachnoid or intraventricular hemorrhage can also cause death acutely due to increased pressures

- Smaller infarcts can affect mobility and cause dysphagia, which would predispose to aspiration pneumonia or other infective causes in both short and longer timescales

- Remote strokes and the associated gliosis can serve as epileptogenic foci, predisposing to seizures and can lead to sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP)

- Finally, it is important to remember that it is common to find incidental chronic and acute infarcts (typically these will be smaller) that could contribute to a clinical picture of vascular dementia while not being directly related to the cause of death.

- It is possible to grade the presence/distribution of microinfarcts as they relate to cognitive impairment (Table adapted from White 2009).

- Lesions can be acute, chronic, related to hypertensive or atherosclerotic disease, be associated with neurodegenerative symptoms, etc. All of this will influence where in the report the findings are listed, and whether they relate to the patient’s cause of death.

Recommended References

- Allinson KSJ. Deaths related to stroke and cerebrovascular disease. Diagnostic Histopathology. 2019; 25 (11), p. 444-452.

- Gray F., Duyckaerts C., & Girolami D. U. Neuropathology of Vascular Disease. In Escourolle & Poirier’s Manual of Basic Neuropathology, 2019. Oxford University Press, 6th edition.

- Reddy H. “Stroke.” Expertpath. 2023. https://app.expertpath.com/document/stroke /6e4ca8a0-5286-446f-9bf5-105a86e4043f.

- Agamanolis D.“Cerebral Infarcts.” Neuropathology-Web.org. 2023. https://neuropathology-web.org/chapter2/chapter2bCerebralinfarcts.html.

Additional References

- Tsao CW, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, Beaton AZ, Bittencourt MS, Boehme AK, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2023 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2023;147:e93–e621.

- Barth RF, Kellough DA, Allenby P, Blower LE, Hammond SH, Allenby GM, Buja LM. Assessment of atherosclerotic luminal narrowing of coronary arteries based on morphometrically generated visual guides. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2017 Jul-Aug;29:53-60. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2017.05.005. Epub 2017 May 30. PMID: 28622581.

- White L. Brain lesions at autopsy in older Japanese-American men as related to cognitive impairment and dementia in the final years of life: a summary report from the Honolulu-Asia aging study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;18(3):713-25. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1178. PMID: 19661625.