Authors: Sam Engrav, John Walsh* MD MHPE

Background

An upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleed is any GI hemorrhage that occurs between the esophagus and before the ligament of Treitz (suspensory ligament of the duodenum) that marks the duodenojejunal junction.

Image: Ligament of Treitz in relation to the duodenum. (Image credit: Bhalla V.P et al.).

Image: Ligament of Treitz in relation to the duodenum. (Image credit: Bhalla V.P et al.).

Various etiologies can result in an upper GI bleed. Often, there will be indications (clinical history, medications, imaging) in a decedent’s medical record that indicate a possible cause for an upper GI bleed, or narrow the differential.

Patients may present with either bright red or dark, “coffee ground” emesis, dizziness, pallor, and abdominal pain. If a bleed is urgent and needs to be located, endoscopy is typically first line as well as lab tests and imaging.

The origin of an upper GI bleed can be divided into the following etiologies:

- Erosive/ulcerative disease

- Gastric/duodenal ulcer (peptic ulcer disease [PUD])

- Esophagitis

- Gastritis/duodenitis

- Portal hypertension complications

- Esophageal/Gastric varices

- Portal hypertensive gastropathy

- Vascular lesions/malformations (unrelated to portal hypertension)

- Angiodysplasia

- Trauma

- Foreign body ingestion

- Mallory-Weiss tear, Boerhaave’s syndrome

- Post procedural/surgical bleeding

- Aortoenteric fistula

- Tumor/malignancy

Of the above noted differential diagnoses, the predominant cause of upper GI bleeds are:

- Erosive/ulcerative etiologies

- Complications of portal hypertension.

- Cirrhosis

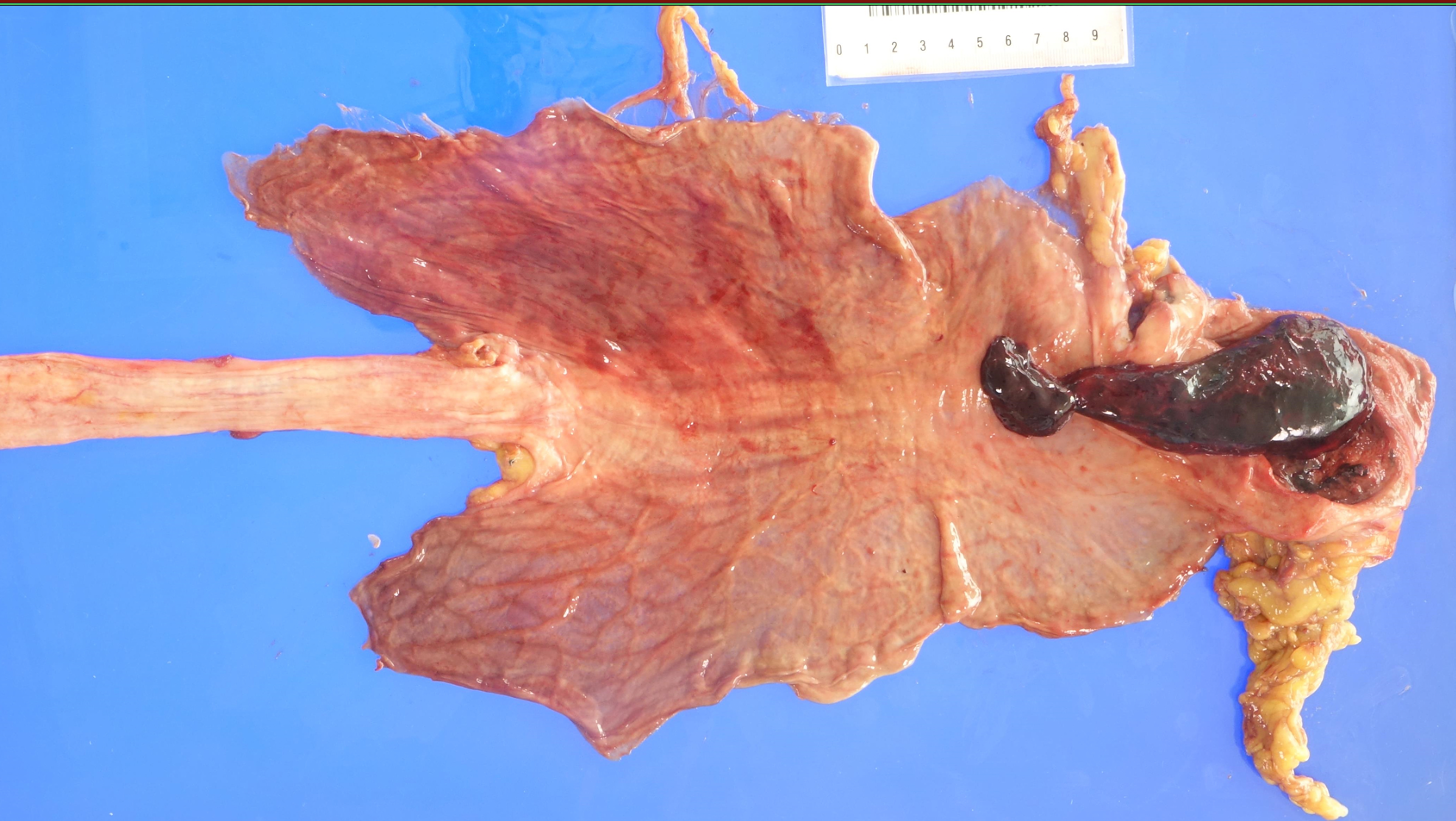

Image: Fatal ruptured pyloric ulcer with large eroded base and adherent clot. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/Stanford Hospital).

Image: Fatal ruptured pyloric ulcer with large eroded base and adherent clot. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/Stanford Hospital).

Quick Tips at Time of Autopsy

Clinical History

The clinical history is crucial in narrowing down the differential of an upper GI bleed. Along with evaluating the decedent’s past medical history, certain labs, imaging, and an in-depth review of medications is useful.

- Past medical history

- Symptoms

- Bleeding

- Hematemesis (frank blood or “coffee-ground” emesis)

- Melena (passage of dark, tarry stools containing digested RBCs)

- Most originates from an upper GI bleed, but can also be due to bleeding in the oropharynx, or rarely, a lower GI bleed

- Hematochezia (passage of bright red or maroon blood/stool per rectum)

- Rare, only in cases of significant upper GI bleed

- Bruising – patients may have diffuse bruises in the setting of liver failure (coagulation factors) which may be due to

- Assault

- Alcohol consumption → stumbling/ falling

- Excessive bruising from normal activities

- Pain

- Abdominal pain

- If pain improves with eating – likely a duodenal ulcer

- If pain worsens with eating -likely a gastric ulcer

- Acid reflux/heartburn

- Abdominal pain

- Dysphagia

- Early satiety

- Constitutional symptoms – malignancy

- Unintentional weight loss, fatigue, cachexia

- Previous upper (or lower) GI bleeds, and cause (if known)

- Peptic ulcer disease

- Zollinger-Ellison syndrome

- H. pylori infection

- Significant nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) usage

- Antithrombotic/anticoagulant use

- Smoking

- Portal hypertension and/or liver disease (Cirrhosis)

- Excessive alcohol use

- History of bleeding disorders

- History of GI malignancy

- History of eating disorders – anorexia nervosa (binge-purge), bulimia nervosa

- History of any thoracic or upper GI procedure/surgery

- Especially sclerotherapy in the setting of varices

- History of Alcohol abuse, Hepatitis or other LIver pathology

- Medications

- Symptoms

- Risk for ulcer induction:

- NSAIDs (even selective COX-2 inhibitors, like celecoxib)

- Antibiotics (many are associated with the potential for pill esophagitis)

- Bisphosphonates

- Medication management of potential/confirmed PUD:

- Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs): omeprazole, lansoprazole, rabeprazole, esomeprazole, pantoprazole

- ***PPIs are available over the counter and may not be listed in an individual’s prescribed medications

- Histamine-2 blockers: famotidine, cimetidine

- Antibiotics (for H. pylori infection) – combination of:

- Triple therapy: PPI + clarithromycin + metronidazole/amoxicillin

- Quadruple therapy: PPI + bismuth subsalicylate + metronidazole + tetracycline

- Anticoagulants/antiplatelets

- Lab Results

- CBC showing microcytic anemia (low hematocrit + low MCV) may be indicative of chronic bleeding

- Elevated BUN/Cr > 30 can indicate upper GI bleeding

- If complications of cirrhosis

- Elevated AST/GGT

- Review INR in individuals with liver disease, underlying bleeding disorders, and/or were on anticoagulants

- Imaging

- Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs): omeprazole, lansoprazole, rabeprazole, esomeprazole, pantoprazole

- Upper endoscopy/esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) is the gold standard for identifying an upper GI bleed

- Can also be used in some circumstances to treat a GI bleed

- CT angiography may also be used to identify the source of a bleed, but if there are any EGD results, those are the most useful

External examination

- External examination is more likely to yield signs of underlying (potentially comorbid) diseases – most notably, cirrhosis

- Look for blood around mouth and anus, abdominal distention, and pale mucous membranes

- A postmortem CT scan can be helpful in identifying areas of radiodensity in the GI tract, which may correlate with the speed and location of the hemorrhage before death.

Internal examination

- Evaluate the GI tract in situ to check for any overt lesions, points of hemorrhage, and/or hypoxic tissue

- Some modification of evisceration technique may be required to optimally identify the source of an upper GI bleed (the goal is to maintain a block including the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum (tied off at the duodenal-jejunal junction at the ligament of Treitz)

- Letulle: Instead of transecting distal duodenum to rectum, make the transection at the duodeno-jejunal junction to better preserve potential lesions in the distal duodenum

- Ghon: Do not remove the esophagus with the thoracic block. Instead, keep the esophagus attached to the stomach – remove it with the stomach/duodenum

- Virchow: Maintain the attachment between the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum. While the stomach can be opened in situ, it may be easier to remove the organ block and open the stomach outside of the body cavity

- If there is a potential for an esophageal variceal bleed, do not longitudinally incise the esophagus

- Open the stomach along the greater curvature, stopping at the gastro-esophageal junction (GEJ), then invert the esophagus through the GEJ to best evaluate for varices

Image: (Left) Dark blue, linear varices at the gastroesophageal junction after the esophagus was inverted at autopsy. (Right) Dark red-black varix at the gastroesophageal junction after the esophagus was inverted at autopsy. (Image credit: WebPath).

Image: (Left) Dark blue, linear varices at the gastroesophageal junction after the esophagus was inverted at autopsy. (Right) Dark red-black varix at the gastroesophageal junction after the esophagus was inverted at autopsy. (Image credit: WebPath).

- Findings

- Duodenal ulcers (especially posterior wall ulcers) are more likely to bleed than gastric ulcers

- Significant bleeding from duodenal ulcers is often due to erosion into branches of the gastroduodenal artery

- Note the amount and distribution of blood in the GI tract, which can help estimate the timing and extent of the bleeding.

- Duodenal ulcers (especially posterior wall ulcers) are more likely to bleed than gastric ulcers

Image: (Left) Ulcer in the upper fundus of the stomach. (Right) Large gastric ulcer. (Image credit: WebPath).

Image: (Left) Ulcer in the upper fundus of the stomach. (Right) Large gastric ulcer. (Image credit: WebPath).

- Mild ischemia may look like normal postmortem changes, while significant ischemia will appear as dusky blue/darkening mucosa with potential bowel dilation

- Smell will be a potent indicator of significant ischemia

- The stomach may have tiny mucosal hemorrhages, these are normal postmortem changes

Image: Multiple superficial gastric erosions with subsequent hemorrhage. (Image credit: WebPath).

Image: Multiple superficial gastric erosions with subsequent hemorrhage. (Image credit: WebPath).

Image: Perforating duodenal ulcer, just distal to the pylorus. (Image credit: WebPath).

Image: Perforating duodenal ulcer, just distal to the pylorus. (Image credit: WebPath).

- Lesion location documentation:

- In esophagus – distance from the GEJ

- In duodenum – distance from the pylorus

Quick Tips at Time of Histology Evaluation

- Depending on the etiology of an upper GI bleed, there may be distinct clues indicating a probable etiology, or nonspecific findings

- Nonspecific signs of ischemia will likely be present in tissues

- Ulcers should be evaluated for size and depth, but will likely only show nonspecific signs of inflammation and/or healing

Image: Low power H&E stain of a gastric ulcer with necrotic debris at the base (black circle) and a bleeding arterial branch (green circle). (Image credit: WebPath).

Image: Low power H&E stain of a gastric ulcer with necrotic debris at the base (black circle) and a bleeding arterial branch (green circle). (Image credit: WebPath).

- If there is a potential of H. pylori infection resulting in an ulcer, a modified Giemsa and/or Warthin-Starry silver stain can be used to identify H. pylori in addition to H&E staining

Image: High power Giemsa stain of H. pylori gastritis. (Image credit:PathOutlines).

Image: High power Giemsa stain of H. pylori gastritis. (Image credit:PathOutlines).

- Mallory-Weiss tears will appear as longitudinal lacerations in the esophagus that extend into the submucosa (but not muscularis propria) that may or may not have signs of an acute inflammatory reaction

- A full-thickness tear of the esophagus indicates Boerhaave syndrome

Quick Tips at Time of Reporting

- Etiology of the bleed is crucial to report (if possible)

- If etiology is unknown after completion of autopsy, can comment on histologic findings

- Example cause of death statements formatted as should be on the death certificate:

- Gastrointestinal hemorrhage

- due to Perforated duodenal ulcer

- due to Chronic H. pylori infection

- Complicated by chronic nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use.

- Esophageal variceal hemorrhage

- due to Portal hypertension

- due to Cirrhosis

- due to Chronic infection with hepatitis C virus.

- Gastrointestinal hemorrhage

References

- Antunes C., Tian C., Copelin EL. Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding – StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf

- Rocky DC. Causes of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in adults. UptoDate. Updated 2024. Causes of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in adults – UptoDate

- Saltzman JR. Approach to acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in adults. UptoDate. Updated 2024. Approach to acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in adults – UptoDate

- Suvarna SK., Sharp AK. Atlas of Adult Autopsy. 2nd ed. Springer Nature Switzerland; 2024.

- Waters BL. Handbook of Autopsy Practice. 4th ed. Totowa (NJ): Humana; 2009.

- Wilkins T., Wheeler B., Carpenter M. Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding in Adults: Evaluation and Management. Am Fam Physician. 2020; 101(5): 294-300. Erratum in: Am Fam Physician. 2021; 103(2): 70.

* The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Navy, Naval Construction Group (NSG) TWO, Uniformed Services University of Health Science, Defense Health Agency, U.S. Navy Bureau of Medicine and Surgery, Department of Defense, or the US Government. The authors report no conflict of interest or sources of funding.