Meagan Chambers MD, Sebastian Lucas BM BCh, Alex Williamson MD

Background

A quick review of terminology

| Term | Definition |

| Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS) | An acute alteration from baseline, without other cause which is due to a wide variety of underlying causes (not just infection). Requires at least 2 of the following: • Temperature >38*C or <36*C • Tachycardia heart rate > 90 beats per minute • Tachypnea respiratory rate > 20 breaths per minute or hyperventilation (PaCO2 < 32 mm Hg) • Abnormal WBC (>12K or <4K per cc or 10% immature bands) |

| Sepsis | Life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection. (Sepsis is SIRS due to an infection) |

| Septic shock | Sepsis-induced hypotension despite adequate fluid resuscitation with perfusion abnormalities. |

| Multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) | Altered organ function in an acutely ill patient such that homeostasis cannot be maintained |

(Table credit: Alex Williamson).

Unknown or unconfirmed diagnoses are frequently discovered at autopsy in patients with sepsis (28% of cases according to Winters et al. 2012).

It is important to keep in mind that sepsis is more than just an infection in a body organ; it includes the body’s immune response to the infection which can damage many organs though cytokine responses.

Review of the postmortem cultures article is highly recommended for any case of sepsis.

Finally, a wide variety of underlying processes may be part of the cause of death in cases of sepsis and these should be appropriately documented as well.

(Figure: Rhee et al. 2019).

(Figure: Rhee et al. 2019).

Image: A cautionary tale. This image is of an autopsy technician’s hand after penetrating injury during an autopsy in a patient with Groups A Strep infection. In this case, no permanent injury resulted from this healthcare-acquired infection, but it is a generous warning for extra care during the autopsy of septic patients. (Image credit: Sebastian Lucas).

Image: A cautionary tale. This image is of an autopsy technician’s hand after penetrating injury during an autopsy in a patient with Groups A Strep infection. In this case, no permanent injury resulted from this healthcare-acquired infection, but it is a generous warning for extra care during the autopsy of septic patients. (Image credit: Sebastian Lucas).

Quick Tips at Time of Autopsy

Clinical History

Information available in the clinical record which should be collected at the time of autopsy includes (but is not limited to)

- Antemortem microbiology results, if available.

- Recent contact with the healthcare setting including prior admissions to a healthcare facility and/or chronic illness requiring frequent healthcare visits.

- Check the patient’s history for clues to possible mimics of septic shock: disseminated malignancy, hemophagocytic syndrome (primary or secondary), Castleman’s disease, thrombotic microangiopathy syndromes, adrenal insufficiency, thyroid storm, pancreatitis, status post coronary artery bypass surgery, drug hypersensitivity reaction, malignant hyperthermia, etc.

- Risk factors for sepsis are linked to immunosuppression and include extremes of age, HIV, transplantation, cancer chemotherapy, diabetes mellitus, chronic ethanol use, liver cirrhosis, and hyposplenism.

External examination

- The external examination should include a thorough inspection for potential (or known) sources of infection.

- Indwelling tubes and lines are commonly overlooked sources, especially cardiovascular access lines, urinary catheters, and surgical drains.

- Skin and soft tissue ulcers are commonly seen in the setting of peripheral vascular disease, diabetes mellitus, and from pressure (e.g. decubitus ulcers).

- If present, properly sample and document all tissue layers of ulcers (from superficial to deep: skin, subcutis, fascia, muscle, bone).

Image: Stages of a pressure ulcer depend on the depth of tissue affected. Note that Stage 1 ulcers do not have any erosion and are limited to superficial erythema. (Image credit: Mira Norian for Verywell Health).

- Skin infections can also be the cause of sepsis (cellulitis, necrotizing fasciitis, etc.), or give clues to its underlying etiology (see images below).

Image: (Top) The characteristic rash of Meningococcal infection. The underlying etiology is due to bacterial vasculitis and thrombosis which will result in a non-blanching rash (see also the histological images below). This contrasts with the bottom image, Group A Strep rash, which is blanching. (Image credits: [Top] Sebastian Lucas and [bottom] Mayo Clinic).

Image: (Top) The characteristic rash of Meningococcal infection. The underlying etiology is due to bacterial vasculitis and thrombosis which will result in a non-blanching rash (see also the histological images below). This contrasts with the bottom image, Group A Strep rash, which is blanching. (Image credits: [Top] Sebastian Lucas and [bottom] Mayo Clinic).

Internal examination

- Large, red, soggy organs

Image: Large, red, soggy organs in a case of sepsis. (Image credit: Sebastian Lucas).

- Common sites of infection include

(Table source: adapted from Novosad et al. 2016).

(Table source: adapted from Novosad et al. 2016).

- Commonly overlooked sources of infection include

- Urolithiasis: at least palpate each ureter, but preferably open them along their length.

- Cholelithiasis: at least palpate the common bile duct, but preferably open it along its length.

Ancillary Testing

- Postmortem microbiology, as indicated and using best practices (Review the linked article for important information).

- Fernandez et. al recommend blood and at least four other tissues: spleen, heart, liver, brain, and both lungs for any case of sepsis without a known source. Additional details in this table.

Quick Tips at Time of Histology Evaluation

- Findings on histology include:

- Spleen with congestion and white pulp atrophy. Of note, this is a non-specific finding that can be seen in chronic immune such as suppression, aging, infections, systemic disease, etc.

Image: Spleen H&Es at low power showing appropriate white to red pulp ratio on the left compared to an age-matched sepsis patient on the right. The septic patient has extensive white pulp atrophy. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/Stanford Hospital).

Image: Spleen H&Es at low power showing appropriate white to red pulp ratio on the left compared to an age-matched sepsis patient on the right. The septic patient has extensive white pulp atrophy. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/Stanford Hospital).

- Liver

- Macrosteatosis can be seen in the setting of sepsis and should not be assumed to be a chronic pathology.

- Hemosiderin laden macrophages are also common.

- Bile ducts may also appear dilated and atrophic in sepsis.

- Sepsis causes cholestasis (and notably, bile increases autolysis which may already be accelerated due to elevated body temperature in patients with sepsis).

Image: H&E (left) showing autolyzed liver; and CD68 (right) staining in the liver demonstrates activated Kupffer cells in this septic patient. As in this case, IHC may clarify the presence and extent of macrophage activation even when there is obscuring postmortem autolysis. (Image credit: Sebastian Lucas).

Image: H&E (left) showing autolyzed liver; and CD68 (right) staining in the liver demonstrates activated Kupffer cells in this septic patient. As in this case, IHC may clarify the presence and extent of macrophage activation even when there is obscuring postmortem autolysis. (Image credit: Sebastian Lucas).

Image: Bone marrow with increased numbers of macrophages, some with hemophagocytosis (black arrows). (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/Stanford Hospital).

Image: Bone marrow with increased numbers of macrophages, some with hemophagocytosis (black arrows). (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/Stanford Hospital).

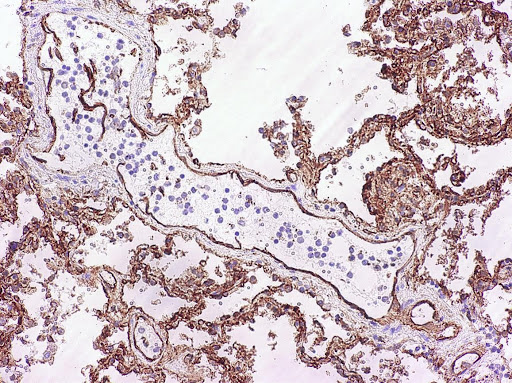

Image: CD54+ (ICAM-1) positive endothelial cells in a lung vessel. Of note, the epithelial positive staining is typical and can act as internal control. (Image credit: Sebastian Lucas).

Image: CD54+ (ICAM-1) positive endothelial cells in a lung vessel. Of note, the epithelial positive staining is typical and can act as internal control. (Image credit: Sebastian Lucas).

- Below is a summary table of useful IHC in the workup of sepsis.

- Where there is doubt that sepsis is present at autopsy, finding no evidence of haemophagocytosis or ICAM-1 up-regulation makes sepsis very unlikely (good negative predictive value).

- Of note, none of these findings is specific for sepsis (uncertain positive predictive value; low sensitivity). ICAM-1 upregulation, for example, can be seen in infections, autoimmune diseases, vasculopathies, and others. Proper clinic-pathologic correlation is required to narrow the differential.

- Fibrin thrombi, particularly in renal glomeruli, are also a common finding in certain sepsis cases, especially meningococcal infections, E. coli infections, and Group A Strep Pyogenes infections.

- These are typically composed of fibrin and platelets.

- Note: these thrombi are to be distinguished from the mainly-platelet thrombi found in thrombotic thrombocytopaemia purpura (TTP), which is unrelated to infection

Image: Two examples of fibrin thrombi in renal glomeruli in sepsis cases. Such disseminated intravascular coagulation (thrombotic microangiopathy) is not specific to sepsis. (Image credit: Sebastian Lucas).

Image: Two examples of fibrin thrombi in renal glomeruli in sepsis cases. Such disseminated intravascular coagulation (thrombotic microangiopathy) is not specific to sepsis. (Image credit: Sebastian Lucas).

- Histological identification of specific infections agents: The standard empirical stains can demonstrate a large proportion of infections that cause sepsis.

- H&E for staphylococci, viral inclusion bodies, helminths

- Grocott silver for fungi and Nocardia

- PAS/GMS for fungi

- Gram stain for gram positive bacteria

- Modified gram stain for certain gram-negative bacteria

- Acid-fast Ziehl-Neelsen stains for mycobacteria

Image: H&E (left) of meningococcal sepsis in the skin with dermal arteritis and secondary thrombosis (results in a non-blanching hemorrhage). The cocci are difficult to spot in this H&E, but are readily apparent in the Brown-Brenn modified gram stain (right). (Image credit: Sebastian Lucas).

Image: H&E (left) of meningococcal sepsis in the skin with dermal arteritis and secondary thrombosis (results in a non-blanching hemorrhage). The cocci are difficult to spot in this H&E, but are readily apparent in the Brown-Brenn modified gram stain (right). (Image credit: Sebastian Lucas).

Image: Streptococcus pneumoniae sepsis: the un-modified gram stain shows the characteristic diplococci. (Image credit: Sebastian Lucas).

Image: Streptococcus pneumoniae sepsis: the un-modified gram stain shows the characteristic diplococci. (Image credit: Sebastian Lucas).

- Evaluate for end-organ injury

(Table Credit: Alex Williamson).

(Table Credit: Alex Williamson).

Quick Tips at Time of Reporting

- Do not write:

“Final Anatomic Diagnoses

1. Clinical sepsis

Autopsy Summary: no source of infection was identified. Clinical correlation recommended.”

This does not represent the work the pathologist has done evaluating all of the above pertinent negatives

- As per CDC guidelines for death certification, include the organism name in the cause of death when possible: e.g. “Community Acquired pan lobar pneumonia due to Streptococcus pneumoniae infection.”

- Click here for examples of final autopsy reports where sepsis is the immediate cause of death

Recommended References

- Garofalo AM, Lorente-Ros M, Goncalvez G, Carriedo D, Ballén-Barragán A, Villar-Fernández A, Peñuelas Ó, Herrero R, Granados-Carreño R, Lorente JA. Histopathological changes of organ dysfunction in sepsis. Intensive Care Med Exp. 2019 Jul 25;7(Suppl 1):45. doi: 10.1186/s40635-019-0236-3. PMID: 31346833; PMCID: PMC6658642.

- C. Stassi, C. Mondello, G. Baldino, E. Ventura Spagnolo, Post-mortem investigations for the diagnosis of sepsis: a review of literature, Diagnostics 10 (2020) 849, https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics10100849

- Fernández-Rodríguez A, Burton JL, Andreoletti L, Alberola J, Fornes P, Merino I, Martínez MJ, Castillo P, Sampaio-Maia B, Caldas IM, Saegeman V, Cohen MC; ESGFOR and the ESP. Post-mortem microbiology in sudden death: sampling protocols proposed in different clinical settings. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2019 May;25(5):570-579. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2018.08.009. Epub 2018 Aug 24. PMID: 30145399.

Additional References

- Winters, B. R., De Sarkar, N., Arora, S., Bolouri, H., Jana, S., Vakar-Lopez, F., … Hsieh, A. C. (2019). Genomic distinctions between metastatic lower and upper tract urothelial carcinoma revealed through rapid autopsy. Clinical Medicine, American Society for Clinical Investigation. doi: doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.128728.

- Novosad SA, Sapiano MR, Grigg C, et al. Vital Signs: Epidemiology of Sepsis: Prevalence of Health Care Factors and Opportunities for Prevention. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:864-69.

- Rhee C, Jones TM, Hamad Y, et al. Prevalence, Underlying Causes, and Preventability of Sepsis-Associated Mortality in US Acute Care Hospitals. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2(2):e187571. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.7571.

- Yan J, Li S, Li S. The role of the liver in sepsis. Int Rev Immunol. 2014 Nov-Dec;33(6):498-510. doi: 10.3109/08830185.2014.889129. Epub 2014 Mar 10. PMID: 24611785; PMCID: PMC4160418.