Authors: Amanda Saunders MD MBA & Desiree Marshall MD

Background

Epilepsy is defined as having at least two unprovoked seizures occurring more than 24 hours apart or one unprovoked seizure with a high likelihood of recurrence. It excludes seizure disorders such as febrile seizures in children, provoked seizures (such as from alcohol withdrawal, head trauma, or tumors), and one-time seizures.

There are multiple underlying causes of seizure disorders, including epilepsy, and the disease can be subdivided into 6 categories: structural, genetic, infectious, metabolic, immune and unknown. Structural causes include severe head trauma, perinatal trauma or tumors. Genetic causes are typically related to underlying congenital malformations that alter the structures of the brain. Infectious causes may include meningitis, encephalitis or diseases such as malaria. Metabolic causes typically have genetic conditions underlying them including Maple Syrup Urine Disease, GLUT 1 deficiency, Organic Acidemia, etc. Immune epilepsy is secondary to an autoimmune disease such as rheumatoid arthritis, Graves’ disease, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, or irritable bowel disease. Approximately half of those with a seizure disorder have no known cause (Middleton 2018).

Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) is a rare, but important cause of death to be aware of when performing an autopsy on a patient with epilepsy. It occurs in approximately 1/1000 individuals with epilepsy and is thought to be increased in those with poorly controlled disease. It is a diagnosis of exclusion and should not be used to describe deaths due to injuries, drowning, status epilepticus or other known causes (8).

Most SUDEP cases will go to the medical examiners, but it is not uncommon to have a death in a person with a seizure disorder history who undergoes a routine medical autopsy. This article adapts forensic principles to the medical autopsy setting.

Quick Tips at Time of Autopsy

Clinical History

- Epilepsy may be unrelated to a patient’s death, and clinical history is one of the most important factors to make this determination. Information should be collected from the medical record and family members such as the frequency of seizures, duration of seizures, age of onset, etc. Additionally, understanding the patient’s clinical management, drug compliance, and any recent changes to medications are also important to consider.

- MRI and EEG can also be helpful clinical correlates.

- If the seizure was witnessed, accurate testimony can be a critical resource to understand the cause and mechanism of death. Specifically, knowing if the patient died during the seizure or in the postictal state, and when injuries may have occurred is extremely relevant to interpreting findings on exam. If the seizure was not witnessed, which is frequently the case, scene findings play a more important role in piecing together what may have happened to the patient.

External examination

- Findings that a seizure occurred around the time of death include tongue biting, head injury, bruises, incontinence, etc.

- It is critical to carefully search and document any amount of traumatic injury, not just to the head, but all over the body and carefully examine the mouth and oral cavity. Have a low threshold for consultation with the local medical examiner’s office if there is concern for a traumatic/accidental death.

Internal examination

- There are no reliable and specific macroscopic findings of a seizure disorder.

- Neuropathologic examination is largely undertaken to exclude any preexisting structural disease. It is extremely uncommon to diagnose seizures at autopsy, but supporting features for an existing diagnosis may be possible to identify.

- Neuropathologic examination may demonstrate the underlying cause of epilepsy such as lesions, tumors, contusions, or infections.

- Subtle neuropathologic findings which are non-specific but may be seen in those with seizure disorders include

- cerebellar, thalamic, and hippocampal atrophy, cortical atrophy

- gliotic foci

- mild edema in SUDEP

- Evidence of seizure disorders can sometimes be seen on histological examination and so ensuring proper sampling is key, even when there are not corresponding macroscopic changes. (Bold represent particularly high yield areas, in the Authors’ opinion).

A proposed sampling protocol includes (Reichard 2014):

- Hippocampus (right and left)

- Amygdala (right and left)

- Watershed (frontal and parieto-occipital parasagittal regions)

- Basal ganglia

- Midbrain

- Pons

- Medulla (at area postrema)

- Hypothalamus

Additional sampling may include

- Thalamus

- Cerebellum (with dentate nucleus)

- Superior temporal cortex

- Mammillary bodies

- Findings not related to the brain which are associated with seizures may include

- Terminal aspiration

- Head trauma

Ancillary Testing

- Toxicology is helpful to determine antiepileptic drug concentration; this can be most helpful in a forensic setting where the patient’s compliance may not be well documented

- CSF may be sent for microbiology evaluation if encephalitis or meningitis is suspected

- If a genetic cause is suspected and molecular testing is clinically indicated and desired by the next of kin, genetic testing can be pursued. Consultation with a genetic counselor is highly recommended.

- Genetic testing is usually done with EDTA whole blood (purple top) or fresh frozen tissue.

Quick Tips at Time of Histology Evaluation

- In most cases, especially with idiopathic or generalized seizures, the brain tissue will appear histologically normal.

- When present, the following findings may support a history of seizures

- Neuronal loss and gliosis, particularly in CA1 (Sommer’s sector) and CA4 regions of the hippocampus. This can progress in severe cases to hippocampal sclerosis.

- Dispersion of the dentate neurons in the granular cell layer

- Gliosis may also be seen in the amygdala in seizure patients

- Evidence of recent, prolonged seizure events (generally lasting 1-2 hours) can include features of hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy due to increased glucose consumption during the seizure and a subsequent energy crisis like that seen in hypoxia.

- Subpial (“Chaslin’s”) gliosis

- As noted previously, underlying developmental disorders can also be found on histology (such as cortical dysplasias, heterotopias, etc.)

Image: H&E’s at 20x of the CA1 area of the hippocampus in patients with hippocampal sclerosis (bottom) and without hippocampal sclerosis (top). The image with hippocampal sclerosis demonstrates loss of neurons and reactive gliosis compared to the case without. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/Stanford Hospital).

Image: H&E’s at 20x of the CA1 area of the hippocampus in patients with hippocampal sclerosis (bottom) and without hippocampal sclerosis (top). The image with hippocampal sclerosis demonstrates loss of neurons and reactive gliosis compared to the case without. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/Stanford Hospital).

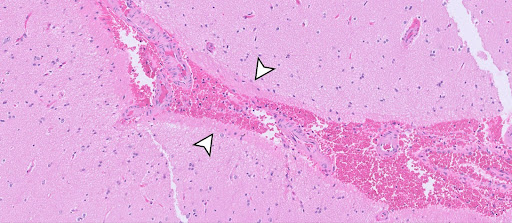

Image: H&E’s at 10x of the dentate nucleus in the hippocampus. The image on the left is a reference hippocampus while the image on the right demonstrates dispersion of the dentate nucleus, particularly in the area with the white arrows. Hippocampal sclerosis with loss of CA4 neurons and reactive gliosis is also present in the right image. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/Stanford Hospital).

Image: H&E’s at 10x of the dentate nucleus in the hippocampus. The image on the left is a reference hippocampus while the image on the right demonstrates dispersion of the dentate nucleus, particularly in the area with the white arrows. Hippocampal sclerosis with loss of CA4 neurons and reactive gliosis is also present in the right image. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/Stanford Hospital).

Image: H&E image of cortex in a seizure patient demonstrating Subpial (“Chaslin’s”) gliosis (White arrows highlight hypereosinophilic layer just underlying the pia/leptomeningeal spaces). (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/Stanford Hospital).

Image: H&E image of cortex in a seizure patient demonstrating Subpial (“Chaslin’s”) gliosis (White arrows highlight hypereosinophilic layer just underlying the pia/leptomeningeal spaces). (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/Stanford Hospital).

Quick Tips at Time of Reporting

- Not finding neuropathologic evidence of epilepsy is common. When present, even suggestive findings such as hippocampal gliosis or sclerosis should be qualified by an appropriate comment such as:

- “This brain demonstrates focal but prominent gliosis in the hippocampus, in bilateral CA4 of the hippocampi (worse on the right than the left). This is a nonspecific finding indicating general injury in the brain. It has been noted in resections associated with seizures and epilepsy (Grote et al. Brain. 2023 Feb 13;146(2):549-560), and may correlate with the patient’s known history of this disorder.”

- In the case of a negative workup, “Given the decedent’s history of seizure disorder, a detailed neuropathological examination was performed after formalin fixation. This revealed a normally formed adult brain with no evidence of pre-existing gross or microscopic structural pathology. As seizures are caused by electrophysiologic processes at the subcellular level, it is not uncommon for a standard neuropathologic evaluation (i.e., detailed visual inspection and light microscopy) to be negative. Detailed neuropathologic examination is a part of a complete examination in these cases to exclude some common and less common causes of seizure disorders, including mass lesions, malformations, chronic traumatic lesions, etc.”

- Example of microscopic description in a negative seizure work up: “Bilateral hippocampi demonstrate normal trilaminar architecture without evidence of hippocampal sclerosis. Dentate gyri show typical configuration and thickness. The amygdalae show expected features. All tissues show typical cytoarchitecture without heterotopias, dysplastic neurons, or balloon cells. No significant inflammation or evidence of neoplasm is appreciated.”

- In many cases, especially in medical autopsies, the history of seizures will not be part of the cause of death statement.

- Alternatively, common causes of death secondary to epilepsy (which could be seen in the medical context) include:

- Status epilepticus

- Airway compromise or aspiration during a seizure

- Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP); of note, SUDEP has both probable and definite categories depending on the situation

Recommended References

- Thom, M. Neuropathology of Epilepsy. Epilepsy Society. Accessed January 9, 2025.

- Middleton, O. Daniel S. Atherton, Elizabeth A. Bundock, Elizabeth Donner, Daniel Friedman, Dale C. Hesdorffer, Heather S. Jarrell, Aileen M. McCrillis, Othon J. Mena, Mitchel Morey, David J. Thurman, Niu Tian, Torbjörn Tomson, Zian H. Tseng, Steven White, Cyndi Wright, Orrin Devinsky. National Association of Medical Examiners Position Paper: Recommendations for the Investigation and Certification of Deaths in People with Epilepsy. Acad Forensic Pathol. 2018 8(1): 119-135.

- Thom M. Guidelines on Autopsy Practice: Deaths in Patients with Epilepsy Including Sudden Deaths Unique Document Number G175 Document Name Guidelines on Autopsy Practice: Deaths in Patients with Epilepsy Including Sudden Deaths.; 2019. Accessed January 9, 2025.

Additional References

- World Health Organization. Epilepsy. World Health Organization. Published February 7, 2024. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/epilepsy

- SUDEP (Sudden Unexpected Death in Epilepsy). CURE Epilepsy. Published August 21, 2024.

- National institute of Neurological Disorders and stroke. Epilepsy and seizures. http://www.ninds.nih.gov. Published July 19, 2024.

- Cihan E, Devinsky O, Hesdorffer DC, et al. Temporal trends and autopsy findings of SUDEP based on medico-legal investigations in the United States. Neurology. 2020;95(7):e867-e877. doi:https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.0000000000009996

- Liu Z, Peravina Thergarajan, Antonic‐Baker A, et al. Cardiac structural and functional abnormalities in epilepsy: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Epilepsia open. 2023;8(1):46-59. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/epi4.12692

- Zhang X, Zhang J, Wang J, Zou D, Li Z. Analysis of forensic autopsy cases associated with epilepsy: Comparison between sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) and not-SUDEP groups. Frontiers in Neurology. 2022;13. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2022.1077624

- CDC. Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy. Epilepsy. Published May 22, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/epilepsy/sudep/index.html

- So EL. What is known about the mechanisms underlying SUDEP? Epilepsia. 2008;49:93-98. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01932.x

- Grote A, Heiland DH, Taube J, Helmstaedter C, Ravi VM, Will P, Hattingen E, Schüre JR, Witt JA, Reimers A, Elger C, Schramm J, Becker AJ, Delev D. ‘Hippocampal innate inflammatory gliosis only’ in pharmacoresistant temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain. 2023 Feb 13;146(2):549-560. doi: 10.1093/brain/awac293. PMID: 35978480; PMCID: PMC9924906.