Authors: Amanda Saunders MD MBA & John Walsh* MD MHPE

Background

Death during or shortly after a surgical procedure is a common occurrence a hospital autopsyist may encounter. Patients may die during the surgery, shortly after or days to weeks later from complications of the surgery. The type of autopsy performed after a surgical related death will vary depending on the procedure and suspected manner in which the patient died as well as local and regional policies and procedures.

- If the death is thought to be secondary to medical error or malpractice, the case may be referred to the local medical examiners/corners for a forensic autopsy.

- The medical examiner / Coroner may decline the case and recommend the treating facility to obtain an autopsy from either an internal autopsy pathologist or an unaffiliated autopsy pathologist.

- In either case, speaking with the surgeon and anesthetist and potentially inviting them to attend the autopsy may be helpful to gain an understanding of everything that happened during the procedure and what interventions were performed.

There are several categories of death to consider:

| Death due to natural disease | Often death secondary to the disease the surgery was trying to correct (ex death from hemorrhage from a ruptured AAA) |

| Death due to complications of surgery | Death related to complications such as wound infection, post operative hemorrhage, etc. |

| Death due to late complication of surgery | Complications after patient is discharged but still related to surgery such as bowel infarction due to adhesions |

| Death due to anesthesia | Typically related to allergy to anesthesia or malignant hyperthermia |

| Death due to metabolic complications | From metabolic alteration such as electrolyte imbalance, diabetic ketoacidosis, or paralytic ileus |

| Death due to medical error | Death directly related to surgery or anesthesia error such as perforation of a major vessel during surgery or premature removal of ET tube |

| Death from unrelated cause | Patient suffers another medical emergency during procedure such as stroke |

Quick Tips at Time of Autopsy

Clinical History

- The most important piece of history in these cases is usually the operative report and notes from the PACU/ICU if applicable

- The pathologist should understand what procedure(s) was performed and why, common complications and rates, what the surgeon/patient’s expectations of the procedure were, and the urgency of the procedure (emergency vs scheduled elective procedure), and the patient’s consent (if applicable).

- Evaluate the patient’s medical history and consider individual risk factors they had prior to the surgery beginning:

- Risk factors for surgery include: age, medical conditions (such as sleep apnea, high blood pressure, diabetes, etc.), obesity, smoking and alcohol use, medications, and previous surgery.

- The American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP) calculator is a tool that can be used to estimate the patient’s surgical risk including the risk of death or serious complications.

(Image credit: ACS NSQIP Surgical Risk Calculator)

The 4 most common postoperative causes of death to be aware of are bacterial sepsis (including pneumonia, urinary tract infection, wound infection, peritonitis), pulmonary emboli, anastomotic breakdown, and hemorrhage. Findings in each of these complications will be discussed further in the internal examination section.

For death to be considered related to anesthesia, it typically has to be within 24 hours of the patient receiving anesthesia, and directly related to the administration or effects of the anesthesia. These deaths can be challenging as they typically have the fewest findings on autopsy, and anesthetic reports and medical dosages are typically relied on to make a determination on cause of death.

External examination

- The body must carefully be examined for surgical scars and wounds and special care should be taken to document any signs of wound dehiscence or nonunion, discharge, signs of infection, etc.

- Dressings covering wounds should be removed for complete examination.

- Examination for any devices that were placed either during surgery or after such as IVs, ET tubes, catheters, drains, etc.

- Search for any external signs of disease such as marbling which may indicate sepsis or petechiae indicating DIC.

- If sepsis is likely the cause of death, cultures should be drawn or collected from the heart of spleen before the body is opened.

- Evidence of sepsis should be looked for in the thorax, subphrenic, and pelvic regions if the patient had cardiac surgery.

Image: Example of petechiae and purpura on upper extremity on post mortem exam. (Image credit: StoryMD).

Image: Example of petechiae and purpura on upper extremity on post mortem exam. (Image credit: StoryMD).

Internal examination

- The body cavities may need to be opened sequentially rather than performing a standard evisceration to allow the pathologist to trace the pathways of a wound or determine if there were complications with implanted devices.

- Ensure traction is not placed on anastomotic sites or this could cause a tear that could be misidentified as anastomotic breakdown (this is especially critical in the bowel).

- Standard autopsy procedures can be followed with alterations depending on what type of surgery the patient underwent.

- If the patient died during a joint replacement or fracture repair, these will often need to be explanted for proper evaluation and possible culture.

- Additional sections of the lungs are often taken to examine for fat emboli with oil red O.

Samples to collect:

(Image credit: Mostafa 2024)

(Image credit: Mostafa 2024)

Findings in the four most common causes of postoperative death:

| Sepsis | Study of 235 patients who died of sepsis found that postmortem, pathologies were detected in the lungs (89.8%), kidneys/urinary tract (60%), gastrointestinal tract (54%), cardiovascular system (53.6%), liver (47.7%), spleen (33.2%), central nervous system (18.7%), and pancreas (8.5%). Additionally, in about 75% of the patients, the autopsy revealed a continuous septic focus which were most commonly pneumonia, tracheobronchitis and peritonitis (Torgersen 2009). |

| Pulmonary embolism | Examine the pulmonary arteries and lobar branches to identify the pulmonary embolism. Additional examination of the lower extremities and dissection of the leg veins should be done to search for DVT as 83% of patients who died from a PE also had a DVT (Sandler 1989). Histology of Pulmonary emboli can be taken.

|

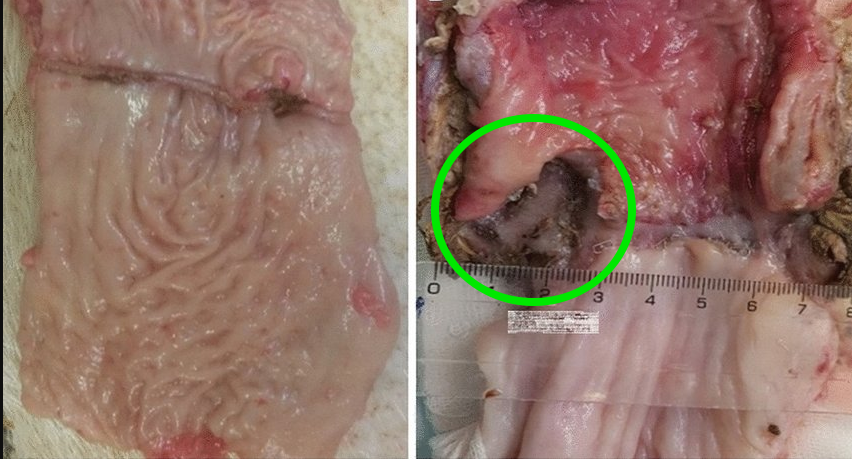

| Anastomotic breakdown | Careful examination of any surgical anastomosis should be performed to identify leaks, tears, or fistulas that could have contributed to the cause of death.

|

| Hemorrhage | Hemorrhage is often obvious on internal exam, once the body cavities are open, but identifying the source may be difficult. This is why opening one cavity at a time and performing a careful examination of anatomical structures is critical to properly identify the source of bleeding.

|

Ancillary Testing

- Toxicology should be considered if the patient is thought to have died secondary to metabolic alteration or drug overdose

- Blood samples from the patient’s hospital admission may still be available for testing as well depending on the timing of surgery and hospital policy for retaining samples.

- Blood, urine, vitreous humour and gastric contents can all be collected for analysis depending on the type of surgery and suspected cause of death in each case.

- As mentioned in the external examination section, if sepsis is suspected blood should be collected peripherally or from the heart prior to opening the body to reduce the risk of contamination.

- If there are areas grossly suspicious for infection, these can be swabbed and sent for culture and sections can be sent for microscopy

- If no gross signs of infection exist but an infectious cause is likely, samples should be collected from the lungs and spleen, as well as urine, blood, bile and CSF.

- If viral infection is suspected, nasal swabs, sections of lung, myocardium or brain can be sent for analysis.

- Radiology may be useful in cases where potential anastomotic breakdown occurred as dye can be injected into vessels or other structures to identify leaks, obstructions or thrombi.

- Blood for genetic testing if concerns for malignant hyperthermia, cardiac channelopathy or other occult process is a consideration.

Quick Tips at Time of Histology Evaluation

- Even if there are no gross findings, sampling of the heart, lungs, liver and kidneys is recommended to rule out underlying microscopic pathology

- Sections from anastomotic sites are recommended to further examine these for breakdown and tissue integrity

- It may be possible to get a vague dating of when a leak started based on histology.

- If grafting was performed on the heart, samples from the grafted area and normal cardiac tissue should be taken to be compared and may even be placed on the same slide.

Quick Tips at Time of Reporting

If the autopsy reveals the cause of death was in fact related to the surgery, the procedure should be included in the cause of death formulation.

Examples of cause of death statements:

- Exsanguination due to intrathoracic hemorrhage due to disruption of aortic suture line due to recent ascending aortic aneurysm repair. Contributing conditions: Hypertension, chronic anticoagulation therapy.

- Cardiac arrhythmia during craniotomy due to air embolism due to venous sinus injury during tumor resection for glioblastoma (CNS WHO Grade 4)

- Septic shock due to intra-abdominal abscess with peritonitis due to anastomotic leak following hemicolectomy. Contributing conditions: Obesity

Recommended References

- Johnson C, Lowe J, Osborn M. London, UK: The Royal College of Pathologists; 2015. Guidance for pathologists conducting post-mortem examinations of individuals with implanted electronic medical devices.

Additional References

- Mostafa HE, Alaa El-Din EA, Albaz AAA, Abdel Moawed DM. Guidelines for Scrutiny of Death Associated With Surgery and Anesthesia. Cureus. 2024;16(10):e70841. Published 2024 Oct 4. doi:10.7759/cureus.70841

- Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation. What are risk factors for surgery? APSF.org. Published October 2021. Accessed July 18, 2025. https://www.apsf.org/patient-guide/what-are-risk-factors-for-surgery/

- An approach to the autopsy examination of patients who die during surgery or in the post-operative period. Burton J. Diag Histopathol. 2019;25:436–443.

- Torgersen C, Moser P, Luckner G, et al. Macroscopic postmortem findings in 235 surgical intensive care patients with sepsis. Anesth Analg. 2009;108(6):1841-1847. doi:10.1213/ane.0b013e318195e11d

- Sandler DA, Martin JF. Autopsy proven pulmonary embolism in hospital patients: are we detecting enough deep vein thrombosis?. J R Soc Med. 1989;82(4):203-205. doi:10.1177/014107688908200407

- Kalvach J, Ryska O, Martinek J, et al. Randomized experimental study of two novel techniques for transanal repair of dehiscent low rectal anastomosis. Surg Endosc. 2022;36(6):4050-4056. doi:10.1007/s00464-021-08726-1

- Ishigami, A., Inaka, S., Ishida, Y., Nosaka, M., Kuninaka, Y., Yamamoto, H., … & Kondo, T. (2024). A case of hemoperitoneum after percutaneous radiofrequency ablation in a patient with hepatocellular carcinoma. Forensic Science, Medicine and Pathology, 20(1), 189-193.

* The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Navy, Naval Construction Group (NSG) TWO, Uniformed Services University of Health Science, Defense Health Agency, U.S. Navy Bureau of Medicine and Surgery, Department of Defense, or the US Government. The authors report no conflict of interest or sources of funding.