Alex Penev MD PhD & Desiree Marshall MD

Background

Infections of the central nervous system (CNS) are relatively rare (compared to other organ systems) due to the protection provided by the axial skeleton, the meninges, and the blood-brain barrier. The bone, dura mater, arachnoid and pia mater divide the CNS into 4 compartments and tend to limit spread of infectious agents between compartments. Infections between the bone and dura (epidural) and in the potential space between the dura and arachnoid (subdural) are relatively rare, with the most common site of infection in the leptomeninges (aka meningitis) (between the arachnoid and pia mater usually involving the cerebrospinal fluid), and finally subpial infections are typically synonymous with intraparenchymal disease (aka encephalitis). The barrier function of CNS anatomy, however, comes at a cost as host defenses are ineffective at controlling active infections once established due to poor accessibility. There are a wide variety of pathogens that can affect the CNS including bacteria, fungi, parasites and viruses, and these agents can present differently clinically and at autopsy. These infections can either be opportunistic, where the disease only affects patients with lower immune resistance, or pathogenic, where most individuals would be affected.

Quick Tips at Time of Autopsy

Clinical History

- Serologic and culture workup pre- and perimortem can help guide your exam, look for positive blood cultures, positive fungal or viral PCR panels, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) studies, etc

- The term “aseptic meningitis” is defined by clinical symptoms consistent with meningitis, without encephalitis, in the absence of positive cultures. Often due to viral infection; however, it can also be related to mycoplasma, rickettsial or parasitic infections.

- Bacterial meningitis often has physical exam findings including rigidity of the neck and involuntary bending of the knees/hips with neck flexion (Brudzinski’s sign) is a classically described maneuver, as is Kernig’s sign, where pain/stiffness is elicited by extending the leg beyond 135 degrees with leg flexed to 90 degrees at the hip. Both of these findings indicate meningeal irritation.

- 20-30% of meningitis patients will present with seizures, focal neurological findings or altered consciousness.

- It is important to note if the patient was immunocompromised – common causes of immune deficiency include HIV infection, chemotherapy, treatment of autoimmune disease, diabetes, congenital genetic syndromes, etc.

- Chronic meningitis can occur in immunocompromised patients, with insidious onset of fever, headache, neck rigidity, nausea, vomiting, confusion and lethargy, etc. – these may exist for a month or longer before presentation.

- Clinical history and mechanism of injury can predispose to differing sites of infection

- Epidural abscesses are typically associated with either adjacent osteomyelitis (often secondary to sinusitis), traumatic injury or surgery. Rarely epidural abscess can be a complication of epidural anesthesia.

- Subdural infections often extend from adjacent sinusitis, otitis or osteomyelitis. Subdural infections in infants are commonly associated with purulent meningitis.

- Cerebral abscesses are not uncommon following purulent meningitis, especially in infants and newborns. Listeria meningitis in particular is associated with multiple microabscess formations (i.e. “Listeria nodules”).

- (Lepto)meningeal infections are typically secondary to hematogenous spread, however recent trauma, surgery or developmental malformations that compromise the blood-brain barrier can also predispose to infection.

- Cerebral abscesses are not uncommon following purulent meningitis, especially in infants and newborns. Listeria meningitis in particular is associated with multiple microabscess formations (i.e. “Listeria nodules”).

- Without preceding meningitis, cerebral abscesses can form following trauma at the site of injury, or through hematogenous spread, in which case lesions are typically found at the grey-white matter junction and are often multifocal. Commonly associated with septic emboli from endocarditis or chronic suppurative intrathoracic infections.

- Bacterial meningitis is commonly caused by different organisms in infants (< 1 year) vs older patients

- Most common are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Neisseria meningitidis (a.k.a. meningococcus) in patients > 1 year old, and are found with roughly equal frequency. S. pneumoniae is most common worldwide.

- N. meningitidis is particularly common in young adults due to its association with crowded living quarters (such as dormitories or military barracks)

- Infants and newborns often present with Listeria monocytogenes, Escherichia coli, Streptococcus agalactiae (group B) and Citrobacter koseri. H. influenzae (Hib) is no longer common due to effectiveness of vaccination.

- Importantly, Tuberculous meningitis is commonly seen in patients from areas with high prevalence of HIV infection

- Viral encephalitides are typically secondary to transmission/infection elsewhere in the body (skin, GI tract, or airways).

- Neuroimaging (ideally MRI) is most helpful in determining if viral (meningo)encephalitis is a possibility – some will have a very specific appearance on MRI, such as HSV encephalitis, which will preferentially affect the temporal horns.

- Most common encephalitides by GI viruses (enteroviridae) used to be poliovirus, but following extensive vaccination are much more rare, now infections by this family are often Group A coxsackievirus and enterovirus 71 (hand, foot and mouth disease), particularly in utero or in neonates/young children.

- Arboviridae transmission (via insect bites) is growing more common in areas previously less affected, often attributed to rising temperatures, common examples include equine encephalitis viruses, West Nile, etc

- Measles can cause encephalitis, particularly in individuals who are not vaccinated (or have waning immunity).

- The most common fungal meningitis is Cryptococcus neoformans, most commonly seen in immunocompromised individuals (especially patients with poorly-controlled HIV).

Image: Initial workup for meningitis includes head imaging, including a CT (shown) or MRI which will demonstrate focal or diffuse leptomeningeal enhancement (the white wispy lines around the periphery of the brain, brain stem centrally, and along fissures laterally). (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

Image: Initial workup for meningitis includes head imaging, including a CT (shown) or MRI which will demonstrate focal or diffuse leptomeningeal enhancement (the white wispy lines around the periphery of the brain, brain stem centrally, and along fissures laterally). (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

External examination

- External signs of meningitis are frequently limited – first priority is to identify any evidence of acute/subacute traumatic injury that can lead to direct seeding/infection.

- However, diffuse purpuric rash, particularly affecting the trunk, arms and legs, should be a significant indication to consider the possibility of meningitis.

Image: A classic rash associated with meningitis has scattered petechiae which can become confluent purpura over time. (Image credit: Child Healthy).

Image: A classic rash associated with meningitis has scattered petechiae which can become confluent purpura over time. (Image credit: Child Healthy).

- Consider sampling CSF with sterile collection for possible cultures before proceeding with the autopsy, as the typical approach to intracranial examination can result in contamination of the CSF with surface pathogens.

- While typical lumbar puncture strategies (targeting L3-L4 space posteriorly) can be used at autopsy, collection from the suboccipital space at the base of the skull with the neck flexed towards the chest is more straightforward.

- CSF can also be sampled relatively cleanly once the cranial cavity has been opened by inserting a needle through the corpus callosum into the lateral ventricles for collection.

- Less important in the context of an infectious investigation at autopsy, it can be useful to note that multiple reports describe differences in the concentration of serum electrolytes between CSF sampled at spinal vs intraventricular sites.

Image: Location of a suboccipital puncture for CSF collection at the time of autopsy. (Image credit: Vicentiu Saceleanu).

Image: Location of a suboccipital puncture for CSF collection at the time of autopsy. (Image credit: Vicentiu Saceleanu).

Internal Examination:

Before the intracranial portion of the exam

- Internal examination findings in the body may raise the suspicion for an occult brain infection including infarcts in other organs (such as the spleen)

- It is important to check for possible sources of septic emboli if cerebral abscess is suspected – most importantly looking for evidence of endocarditis on cardiac valves (esp mitral/aortic), or abscesses in the head/neck will be the highest yield (though thoracic/peripheral abscesses can also lead to abscess seeding, especially if there is a patent foramen ovale present). Post-traumatic and post-procedural abscesses should be associated with some defect or wound that served to introduce the pathogen.

Leptomeninges

- In cases of acute bacterial meningitis (sometimes aptly called “purulent meningitis”), a purulent exudate can typically be seen involving the leptomeninges and anywhere in contact with CSF (can track down cranial nerves, spinal roots, in Virchow-Robin spaces, etc.

- After multiple weeks (as in chronic meningitis), this exudate will typically organize and will appear like fibrous connective-tissue – this can sometimes result in obstructive hydrocephalus (possibly with dilated ventricles) due to obstruction of CSF outflow tracts

- Given enough time, the infection can spread into the subpial and subependymal spaces, even causing cerebral abscesses secondary to direct extension, particularly in infants and newborns.

- Typical presentation of tuberculous meningitis is gray-green opacity and thin fibrous tissue thickest over the base (filling basal cisterns, extending into Sylvian fissure and cisterna magna) sometimes involving the spinal cord and also with thin exudate over the cerebral convexities. Tubercles are rare to see in the brain, but can also often see areas of ischemia (especially in basal ganglia) associated with endarteritis obliterans.

Parenchyma

- Petechial hemorrhages in the brain and/or spinal cord should raise concern for an infection with embolic processes (i.e. septic embolization) and/or microangiopathy.

- Cerebral abscesses will present with a spectrum of findings over time

- Days 1-3: acute/focal cerebritis will appear as an ill-defined area of redness (hyperemia) with associated edema that adds to the mass effect of the lesion.

- Days 4-9: late cerebritis typically presents with a necrotic and purulent center resulting from a confluence of multiple necrotic centers, sometimes surrounded with a thin layer of inflammatory granulation tissue that can be difficult to see grossly.

- Days 10-13: an early abscess capsule can typically be appreciated; it is thickest at the cortical surface and often thinnest (sometimes indistinguishable) on the ventricular surface.

- Day 14+: the established capsule thickens and can be easily stripped away from the surrounding brain parenchyma with edema.

- Fungal cerebral infections vary in their specific presentations, but will have some combination of features similar to exudate seen in tuberculous meningitis (some will form nodules) with variable amounts of abscess formation.

- Viral meningitis/encephalitis will have very subtle gross lesions if any, generally limited to hyperemia and often adjacent edema. Some viruses will cause degeneration in the white matter tracts specifically. In severe cases, areas of necrosis can be identified.

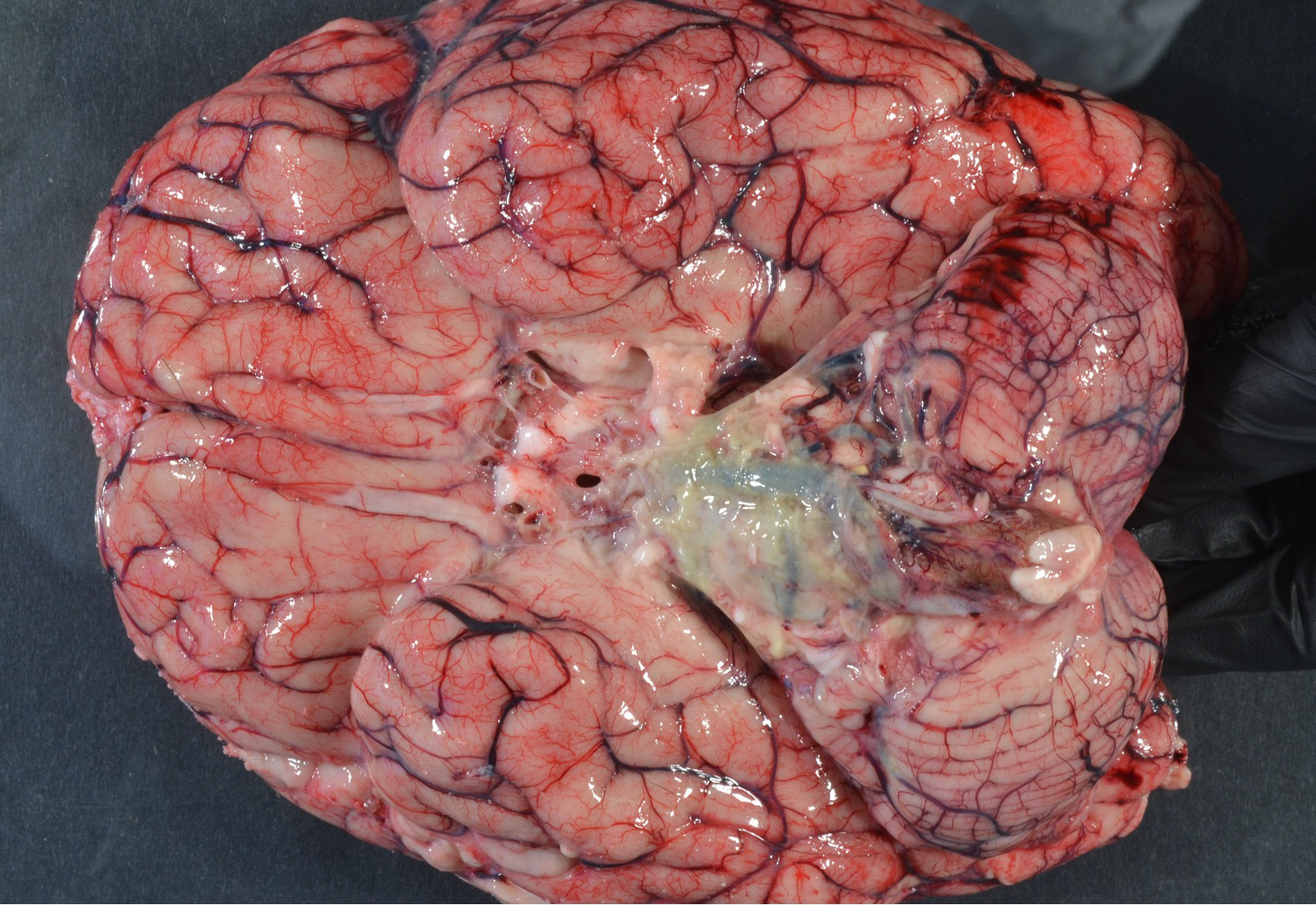

Images: Multiple examples of cerebral abscesses on gross examination. (Image Credits: Dr. Alvord Shaw/University of Washington).

Images: Multiple examples of cerebral abscesses on gross examination. (Image Credits: Dr. Alvord Shaw/University of Washington).

Image: Acute bacterial meningitis demonstrating purulent exudate along the basilar meninges. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

Image: Acute bacterial meningitis demonstrating purulent exudate along the basilar meninges. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

Image: Tuberculous meningitis may appear grossly similar to other forms of meningitis with basilar predominant meningeal opacities and thickening. (Image credit: Dr. Alvord Shaw/University of Washington.

Image: Tuberculous meningitis may appear grossly similar to other forms of meningitis with basilar predominant meningeal opacities and thickening. (Image credit: Dr. Alvord Shaw/University of Washington.

Image: Dusky ischemic changes from HSV encephalitis, classically in the temporal lobe(s). (Image Credit: Dr. Alvord Shaw/University of Washington).

Image: Dusky ischemic changes from HSV encephalitis, classically in the temporal lobe(s). (Image Credit: Dr. Alvord Shaw/University of Washington).

Image: Chronic HSV encephalitis (two years post treatment) demonstrates marked cavitation and remodeling (i.e. cystic encephalomalacia) of the bilateral temporal lobes (right greater than left). Evident on histologic examination was extension into the brainstem. (Image credit: Stanford University/Meagan Chambers).

Image: Chronic HSV encephalitis (two years post treatment) demonstrates marked cavitation and remodeling (i.e. cystic encephalomalacia) of the bilateral temporal lobes (right greater than left). Evident on histologic examination was extension into the brainstem. (Image credit: Stanford University/Meagan Chambers).

Ancillary Testing

- Tissue and CSF culture and/or PCR speciation results are more sensitive than peripheral blood cultures, as well as histologic and immunohistochemical stains on CNS tissue.

- PCR for speciation is very sensitive for viral agents and can also be used to screen for an array of bacterial and fungal agents too using 16S ribosomal RNA sequences

- Swabbing the meninges is a quick and easy option to work up infection, especially when the exam is already underway and CSF may be contaminated.

- A piece of fresh frozen brain with overlying meninges can also be used for general infectious testing (including, viral testing, depending on lab preferences/requirements).

- Specialized testing for specific organisms may be warranted on a case by case basis.

- Latex agglutination tests using pathogen-specific antibodies are commonly used to test for S. pneumoniae, N. meningitidis, group B Streptococcus, H. influenzae type B, Escherichia coli, and Cryptococcus

- Lateral flow immunochromographic assays are available for rapid and cost-effective testing for Cryptococcus as well as S. pneumoniae and N. meningitidis which can serve as an effective surrogate for direct culture

- For additional information see the Postmortem Cultures Article.

Quick Tips at Time of Histology Evaluation

- Bacterial meningitis on histology will have abundant neutrophils in both the tissue of the leptomeninges and in associated fibrino-purulent debris in the leptomeningeal spaces. Some bacteria can be seen either free-floating in aggregates or within neutrophils. The neutrophilic inflammation can be present wherever CSF contacts including the Virchow-Robbin’s spaces, walls of leptomeningeal blood vessels, cranial nerves, spinal roots and ventricular walls (resulting in purulent ventriculitis). As time progresses, the purulent material will organize into fibrous tissue and fibrin with associated histiocytes, plasma cells and lymphocytic inflammation.

- At the time of histology, routine bug stains can be used to assist with identifying the infectious agent (e.g. Brown and Brenn/tissue gram stain for bacterial organisms, IHC for viral infections such as HSV/CMV/EBV, Grocott–Gömöri’s methenamine silver stain [GMS] for fungal organisms, and acid-fast bacilli [AFB] for tuberculous meningitis).

- In cerebral abscesses, the histologic evolution mirrors the changes in gross appearance

- Days 1-3: early parenchymal necrosis is present with vascular congestion, possible microhemorrhages, microthrombi and perivascular exudate with associated edema and neutrophilic inflammation.

- Days 4-9: there is a central fibrino-purulent collection with thin granulation tissue with a complement of neutrophils, macrophages and lymphocytes; in adjacent areas there is perivascular cuffing with a mix of neutrophils and lymphocytes.

- Days 10-13: the peripheral granulation tissue starts to appear more thickened and organized (recruitment of fibroblasts) with neovascularization and there is a broad complement of chronic inflammatory cells including lymphocytes, monocytes, plasma cells and macrophages.

- Day 14+: the abscess cavity is fully matured with roughly 5 histologically apparent layers, consisting of 1) necrotic tissue center with macrophages, 2) thickened granulation tissue with proliferating fibroblasts and radially oriented blood vessels, 3) a peripheral zone of plasma cells and lymphocytes, 4) dense, gliotic/fibrous tissue with reactive astrocytes and 5) a zone of adjacent parenchymal tissue with significant edema.

Image: Mixed leptomeningeal inflammation associated with bacterial meningitis. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

Image: Bacterial colonies tracking along perivascular/Virchow-Robins’ spaces (which are confluent with meningeal vessels) can be seen in some cases. This should not be confused with hematogenous dissemination of infection. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

Image: Meningitis may elicit a superficial encephalitis in adjacent tissue as seen here even though the leptomeninges have been stripped away. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

- Tuberculous meningitis will have similar features with classical non-caseating granulomas cuffed with histiocytes, lymphocytes and fibroblasts.

- Similarly, fungal infections can cause similar acute inflammatory tissue reactions (sometimes with increased eosinophils) which then evolve into chronic lesions with granulomas and organizing fibrosis. A notable difference is that many fungal organisms will target adjacent arteries and will cause relatively extensive ischemia and necrosis due to vascular obliteration.

Image: In this case of fungal meningitis the inflammation is lymphocyte-rich rather than neutrophil rich. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

Image: In this case of fungal meningitis the inflammation is lymphocyte-rich rather than neutrophil rich. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

- Similar to their gross appearance, viral infections of the meninges and cerebral parenchyma will demonstrate vascular congestion and variable amounts of lymphocytic inflammation, typically in a perivascular distribution as well as in the choroid plexus.

- Histologic findings associated with viral CNS infections include microglial nodules and neuronophagia (as a precursor to microglial nodules).

Quick Tips at Time of Reporting

- An excellent guide to interpreting CSF studies can be found here.

- Whenever possible, report site, type (e.g. abscess, meningitis) and a rough chronicity of lesions.

- Mechanism is an important consideration when characterizing cause of death, as even a remote traumatic event that serves as an infectious exposure can contribute to death later on.

- Post-procedural or penetrating head trauma can directly seed the cranial cavity or brain parenchyma.

- Cerebral abscess can be complicated by hemorrhage due to the friability of the inflamed tissue, which can be fatal.

- Post-infectious encephalitis, often called acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) can be a later complication of systemic viral illness, generally with a 3 week latency period. Acute hemorrhagic leukoencephalitis (AHL) is similar but more rapidly fatal post-viral complication.

- Chronic meningitis with organizing exudates (as well as acute to subacute cerebral abscesses) can cause obstructive hydrocephalus that can progress to herniation and death due to mass effect.

Recommended References

- Balitzer D, Weiss T. Meningitis. On ExpertPath. Accessed June 2024 (Login Required).

- Gray F., Duyckaerts C., & Girolami D. U. Infections of the Central Nervous System. In Escourolle & Poirier’s Manual of Basic Neuropathology, 2019. Oxford University Press, 6th edition.

- Agamanolis D .“Infections of the Central Nervous System.” Neuropathology-Web.org. 2023. https://neuropathology-web.org/chapter5/chapter5aSuppurative.html#meningitis

Additional References

- Brooks EG, Utley-Bobak SR. Autopsy Biosafety: Recommendations for Prevention of Meningococcal Disease. Acad Forensic Pathol. 2018 Jun;8(2):328-339. doi: 10.1177/1925362118782074. Epub 2018 Jun 6. PMID: 31240046; PMCID: PMC6490128.Paulina Wachholz, Rafał Skowronek and Natalia Pawlas. Cerebrospinal fluid in forensic toxicology: Current status and future perspectives. Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine, 2021-08-01, Volume 82, Article 102231.

- Ridpath AD, Halse TA, Musser KA, Wroblewski D, Paddock CD, Shieh WJ, Pasquale-Styles M, Scordi-Bello I, Del Rosso PE, Weiss D. Postmortem diagnosis of invasive meningococcal disease. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014 Mar;20(3):453-5.