Authors: Sam Engrav & Desiree Marshall MD

Background

Cerebral herniation describes a phenomenon wherein brain tissue compresses against and/or passes through/under rigid structures in the skull due to increased intracranial pressure.

These patterns are frequently, but not always, dictated by the location of the pathology contributing to the herniation.

There are different types of cerebral herniation described by what region of the brain herniates and the directionality of the shift.

- Uncal/Descending Transentorial: the uncus of the temporal lobe herniates medially and/or downward through the opening of the tentorium cerebelli

- Cerebellar/Ascending Transtentorial: the cerebellar tonsils and/or vermis herniate upward through the opening in the tentorium cerebelli

- Usually the result of a posterior fossa tumor or cerebellar bleed

- Central Transtentorial: diencephalon, midbrain, and/or portions of the temporal lobe(s) herniate downward through the tentorium cerebelli

- Cerebellar Tonsillar: cerebellar tonsils herniate downward into the foramen magnum

- Transfalcial/Subfalcine/Cingulate: one of the hemispheres crosses the midline below the falx cerebri

- Transcalvarial: a portion of the brain herniates outward through a craniotomy opening (often performed to treat high intracranial pressure and avoid downward herniation)

Image: Diagram illustrating different types of brain herniation. (Image credit: Wikimedia Commons 2016).

Image: Diagram illustrating different types of brain herniation. (Image credit: Wikimedia Commons 2016).

Image: Grossly, ventral displacement of the cerebellar vermis into the dorsal pons is appreciated, consistent with upward transtentorial herniation (left image). Microscopically (right image), Duret hemorrhages of the dorsal pons and severe compression of the 4th ventricle is appreciated. This compression compromises many vital structures within the dorsal pons, including the superior cerebellar peduncle, spinocerebellar tract, trigeminal nuclei, and the locus coeruleus. Upward transtentorial herniation is less common than others and is caused by posterior fossa mass effect (e.g., cerebellar tumor, hemorrhage, edema, or obstructive hydrocephalus). (Image credit: John Newman/Stanford Hospital.)

Image: Grossly, ventral displacement of the cerebellar vermis into the dorsal pons is appreciated, consistent with upward transtentorial herniation (left image). Microscopically (right image), Duret hemorrhages of the dorsal pons and severe compression of the 4th ventricle is appreciated. This compression compromises many vital structures within the dorsal pons, including the superior cerebellar peduncle, spinocerebellar tract, trigeminal nuclei, and the locus coeruleus. Upward transtentorial herniation is less common than others and is caused by posterior fossa mass effect (e.g., cerebellar tumor, hemorrhage, edema, or obstructive hydrocephalus). (Image credit: John Newman/Stanford Hospital.)

Quick Tips at Time of Autopsy

Clinical History

There are multiple potential etiologies for an increase in intracranial pressure – the associated clinical histories, risks, and appropriate antemortem data will be driven by the potential etiology.

- Clinical/presentation history

- Hemorrhage – Head trauma or history suggestive of sudden onset headache (“thunderclap headache”). See Meningeal Bleeds for additional information on intracranial hemorrhage.

- Also, coagulopathy (including therapeutic blood thinners), malignancy, preexisting vascular disease or congenital vascular malformations, hypertension, previous ischemic infarcts

- Tumors – Any history of primary brain cancer or metastatic cancer that has spread to the brain

- Abscess/Cyst/Infection – Infectious symptoms paired with focal neurologic deficits

- Risk factors: Recent travel, consumption of undercooked meat/seafood, procedures involving the face, head, neck, and/or skull, indwelling lines/tubes/hardware as sources of infection

- Inflammation from a recent intracranial procedure or trauma to the skull/brain

- Acute onset generalized edema (e.g. hypertensive encephalopathy, hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy such as after CPR with ROSC, etc.)

- Hemorrhage – Head trauma or history suggestive of sudden onset headache (“thunderclap headache”). See Meningeal Bleeds for additional information on intracranial hemorrhage.

- Evolution of symptoms over time suggestive of a central nervous system etiology include: change in level of consciousness, development of new focal neurologic deficits, posturing, hypo/hyperreflexia, etc.

- A new fixed and dilated pupil is the hallmark of uncal herniation due to compression of the ipsilateral oculomotor nerve.

- Hemiparesis may also be present due to compression of the cerebral peduncle, specifically the contralateral corticospinal tract fibers. [Kernohan’s notch is a neurological condition that occurs when the cerebral peduncle is indented due to a lesion on the opposite side of the brain. It’s also known as the Kernohan-Woltman notch phenomenon (KWNP). Symptoms include hemiparesis on the side opposite the brain lesion, altered consciousness, and pupillary asymmetry. Classically, there can be false localization on the ipsilateral side but pathology is on the contralateral side.]

- Other findings with uncal herniation include secondary temporal and occipital lobe infarcts (compression of the posterior cerebral artery), and hydrocephalus (compression of the aqueduct of Sylvius).

- Progressive central herniation can lead to oculomotor palsy, progressive alteration of consciousness, decerebrate posturing, coma, and eventually death

- A new fixed and dilated pupil is the hallmark of uncal herniation due to compression of the ipsilateral oculomotor nerve.

-

- Antemortem data in medical record

- CSF (Lumbar puncture): blood or infection

- Diagnoses/lab results confirming risk factors for coagulopathy: CBC, platelets, PT, PTT, INR, D-dimer, hereditary coagulopathy studies)

- Microbiology testing

- Imaging indicating trauma, infection (abscess), generalized edema, or malignancy in the cranial vault (fracture, tumor, hemorrhage, etc.)

- Antemortem data in medical record

- Radiography may also suggest herniation and can support the autopsy examination. (An excellent article demonstrating normal radiographic anatomy alongside radiographic findings of herniation is provided by Riveros 2019).

-

- Any history of chronic illness with acute change (e.g. acute decompensated liver failure in the setting of chronic liver disease)

- Surgical history, especially interventions of the skull, dura, or brain itself (tumor debulking/removal, surgical decompression, etc.)

Image: Transtentorial herniation on CT. Radiography demonstrates midline shift (long arrow), swelling and loss of gyral spaces on the right side of the brain, and compression of the brain onto the falx (arrow heads). (Image credit: Riveros 2019).

Image: Transtentorial herniation on CT. Radiography demonstrates midline shift (long arrow), swelling and loss of gyral spaces on the right side of the brain, and compression of the brain onto the falx (arrow heads). (Image credit: Riveros 2019).

External examination

- Evidence of head trauma

- Lacerations, contusions, abrasions, etc. indicative of head trauma

- Document location, size, and description

- Bruising over the mastoid process – potential basilar skull fracture

- Periorbital bruising – potential epidural/subdural bleed in the setting of basilar skull fracture

- Blood or CSF leaking from ears and/or nose

- Lacerations, contusions, abrasions, etc. indicative of head trauma

- Evidence of other malignancy

- Ports, lines, or other therapeutic interventions

- Evidence of late-stage disease – pressure ulcers, significant weight loss, obvious masses or other lesions

- Evidence of potential source of infection

- Indwelling lunes, tubes, ports, drawings, etc.

- Evidence of surgical intervention – as therapy for the underlying etiology or for means of acute decompression

- Burr holes

- Healing craniotomy/hemicraniectomy

- Catheters, VP-shunt tube

- Surgical clips, coils, stents, etc.

Internal examination

- After fixation, the brain should be examined for herniations. Key indicators of herniation include:

- Migration of brain tissue through skull foramina, craniotomy site, and/or under/around the falx cerebri/tentorium cerebelli. When severe, the portion of the brain that herniated will exhibit molding/warping

- Midline shift and/or asymmetry of the cerebral hemispheres

- Effacement or asymmetry of cerebral gyri

- Evidence of infarct – hemorrhagic or ischemic (due to compression, and in extreme cases, laceration)

- Hemorrhage and/or discoloration of the adjacent brain areas experiencing increased pressure (but which are not necessarily herniated)

- Softening of the herniated tissue due to ischemia and necrosis from herniation

Subfalcine Herniation:

Image: Subfalcine herniation with shift of brain mass from right to left in the image. A red line denotes the usual position of the midline of the interhemispheric fissure and the dural falx. The cingulate gyrus is pushed under the dura (the dura is not present) to the left. There is cortical hemorrhage and discoloration where the tissue has herniated due to compressional forces and consequent ischemia. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/Stanford Hospital).

Image: Subfalcine herniation with shift of brain mass from right to left in the image. A red line denotes the usual position of the midline of the interhemispheric fissure and the dural falx. The cingulate gyrus is pushed under the dura (the dura is not present) to the left. There is cortical hemorrhage and discoloration where the tissue has herniated due to compressional forces and consequent ischemia. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/Stanford Hospital).

- Subfalcine herniation can be observed before cutting in many cases by looking into the interhemispheric fissure. A “shelf” of tissue will be seen which will obscure the corpus callosum (in part or in whole).

Image: This image looks down the two hemispheres which are being gently spread open to reveal the corpus callosum at the bottom of the fissure. This brain is not herniated and is meant to show the normal view. Subfalcine herniation would create a shelf of tissue deep in the fissure. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/Stanford Hospital).

Image: This image looks down the two hemispheres which are being gently spread open to reveal the corpus callosum at the bottom of the fissure. This brain is not herniated and is meant to show the normal view. Subfalcine herniation would create a shelf of tissue deep in the fissure. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/Stanford Hospital).

- Subfalcine herniation is best appreciated on cross sections of the brain (as demonstrated above and below) where the herniation is easily viewed and measured. Additionally, it avoid potential tissue disruption which can happen when viewing the fissure.

Image: measuring subfalcine herniation involves measuring the tissue that is displaced from midline. In this image, the red line represents midline and the yellow line is the measure of herniation. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/Stanford Hospital).

Image: measuring subfalcine herniation involves measuring the tissue that is displaced from midline. In this image, the red line represents midline and the yellow line is the measure of herniation. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/Stanford Hospital).

Uncal herniation:

Image: normal uncinate processes (white arrows) as viewed from the inferior aspect of the brain (the right image is the close up of the yellow box on the left image). There is a physiologic groove present in non-herniated cases from the impression of the tentorium (yellow lines on the left image). (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/Stanford Hospital).

Image: normal uncinate processes (white arrows) as viewed from the inferior aspect of the brain (the right image is the close up of the yellow box on the left image). There is a physiologic groove present in non-herniated cases from the impression of the tentorium (yellow lines on the left image). (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/Stanford Hospital).

- Uncal herniation (of the uncinate processes) may look identical to the physiologic groove demonstrated in the above photo.

- There is substantial variation in the measure of the medial projection of the uncinate processes beyond the tentorial physiologic groove. The size alone is not an indicator of the presence or magnitude of herniation. (For example, in the above photo, the left tissue projection is naturally smaller than the right).

- Clues to herniation include discoloration, hemorrhage, and/or tissue softening on the uncinate processes or on the medial aspect of the adjacent temporal lobe (where it is pushing on the sphenoid bone).

Image: This brain has a left-sided hemorrhagic contusion with swelling. The area of the circle of Willis (the right image is the close up of the yellow box on the left image) is magnified to show frank uncal herniation on the side with the bleed (red arrow); the necrotic tissue has expanded out of its normal position (the physiologic groove cannot be seen) to impinge on the large vessels of the Circle of Willis. On the other side, the normal physiologic groove can be seen but there are candidate foci of hemorrhage from increased pressure (white arrow).

Image: This brain has a left-sided hemorrhagic contusion with swelling. The area of the circle of Willis (the right image is the close up of the yellow box on the left image) is magnified to show frank uncal herniation on the side with the bleed (red arrow); the necrotic tissue has expanded out of its normal position (the physiologic groove cannot be seen) to impinge on the large vessels of the Circle of Willis. On the other side, the normal physiologic groove can be seen but there are candidate foci of hemorrhage from increased pressure (white arrow).

Image: Uncal/parahippocampal (white arrows) herniation result in a tight space between the brainstem and the hemispheres, as well as brainstem hemorrhage (yellow arrow). (Image credit: Desiree Marshall/King County Medical Examiner’s Office).

Image: Uncal/parahippocampal (white arrows) herniation result in a tight space between the brainstem and the hemispheres, as well as brainstem hemorrhage (yellow arrow). (Image credit: Desiree Marshall/King County Medical Examiner’s Office).

- Other findings with uncal herniation include temporal and occipital lobe infarcts (compression of the posterior cerebral artery), and hydrocephalus (compression of the aqueduct of Sylvius).

Image: (Left) Right uncal herniation with associated PCA compression with medial occipital acute infarct. (Right) Cross section of the same case showing acute infarction of right inferior-medial occipital lobe. (Image credit: Desiree Marshall/King County Medical Examiner’s Office).

Image: (Left) Right uncal herniation with associated PCA compression with medial occipital acute infarct. (Right) Cross section of the same case showing acute infarction of right inferior-medial occipital lobe. (Image credit: Desiree Marshall/King County Medical Examiner’s Office).

Central transtentorial herniation:

- In central transtentorial herniation, there is descent of the diencephalon, midbrain, and pons

- It is often seen along with uncal herniation. (Recall that both are downward transtentorial herniations).

- Other findings include medial lateral compression of the brainstem

- A rough measure adapted from radiology uses a ruler connecting the two hippocampi bilaterally. If the red nucleus lies below the line, it is herniated.

Image: Coronal section of a reference brain at the level of the lateral geniculate nucleus demonstrates left and right hippocampi with the top most section of the midbrain between them. This is the section at which central transtentorial herniation can be measured using radiographic techniques (see next image). (Image credit: Desiree Marshall/King County Medical Examiner’s Office).

Image: Coronal section of a reference brain at the level of the lateral geniculate nucleus demonstrates left and right hippocampi with the top most section of the midbrain between them. This is the section at which central transtentorial herniation can be measured using radiographic techniques (see next image). (Image credit: Desiree Marshall/King County Medical Examiner’s Office).

Image: In this close up of the image above, a black line is added connecting the center of the hippocampi. The substantia nigra (white arrows) can be seen bilaterally. This is at the same level as the red nucleus (inset: midbrain tracts showing substantia nigra and red nuclei). The substantia nigra/red nuclei are level with the hippocampi in this brain without herniation. A brain with transtentorial herniation would push the red nuclei below the hippocampi. This displacement downwards can be measured with a ruler. (Image credit: Desiree Marshall/King County Medical Examiner’s Office).

Image: In this close up of the image above, a black line is added connecting the center of the hippocampi. The substantia nigra (white arrows) can be seen bilaterally. This is at the same level as the red nucleus (inset: midbrain tracts showing substantia nigra and red nuclei). The substantia nigra/red nuclei are level with the hippocampi in this brain without herniation. A brain with transtentorial herniation would push the red nuclei below the hippocampi. This displacement downwards can be measured with a ruler. (Image credit: Desiree Marshall/King County Medical Examiner’s Office).

- A significant complication of transtentorial herniation is a Duret hemorrhage – a secondary hemorrhage of the midbrain and pons as a result of rapid, asymmetric herniation of the brainstem downward – this indicates irreversible damage of the reticular formation of the brainstem, and often results in death.

- It is frequently observed in midline region of the pons, but can extend to paramedian, and ventral regions as well (and the midbrain) – the result of shearing/stretching of the perforating basilar artery branches

- Can be large or small

- Size is not correlated to severity of antemortem symptoms/clinical observations

- Often occurs when there is a rapid, asymmetrical, downward herniation of the brainstem

Image: example of Duret hemorrhages. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/Stanford Hospital).

Image: example of Duret hemorrhages. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/Stanford Hospital).

Tonsillar Herniation:

Image: This photo demonstrates the physiologic tonsillar projections. These are highly variable between individuals. These areas can become more prominent, soft and necrotic, and/or disrupted in cases of herniation. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/Stanford Hospital).

Image: This photo demonstrates the physiologic tonsillar projections. These are highly variable between individuals. These areas can become more prominent, soft and necrotic, and/or disrupted in cases of herniation. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/Stanford Hospital).

- As with uncal herniation, tonsillar herniation may look identical to the physiologic groove demonstrated in the above photo. Clues to herniation include

- a soft texture, discoloration, and/or punctate hemorrhages

- fullness, or narrowing of the space between the brainstem and the tonsils often resulting in indentation of the tonsils on the medulla

Image: In this trauma case there is severe narrowing of the space between the tonsils and the brain stem (red arrow), as well as associated bruising from increased pressure on the tonsils (white arrow). (Image credit: Desiree Marshall/King County Medical Examiner’s Office).

Image: In this trauma case there is severe narrowing of the space between the tonsils and the brain stem (red arrow), as well as associated bruising from increased pressure on the tonsils (white arrow). (Image credit: Desiree Marshall/King County Medical Examiner’s Office).

- Also as with tonsillar herniation, there can be frank tissue disruption consistent with herniation (photo below).

Image: At the base of the brain stem there is cauliflower-like herniation of the tonsils around the brainstem bilaterally (red circle). (The photo on the right is the enlarged picture of the white box on the left). (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/Stanford Hospital).

Image: At the base of the brain stem there is cauliflower-like herniation of the tonsils around the brainstem bilaterally (red circle). (The photo on the right is the enlarged picture of the white box on the left). (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/Stanford Hospital).

- If not already known, the external examination may reveal potential etiologies for herniation

- Signs of hemorrhage (epidural, subdural, subarachnoid: see the Meningeal Bleeds article).

- Skull trauma (fractures, surgical interventions, hardware) can indicate a potential route of infection/inflammation, trauma, previous lesion, and/or confirm interventions

- Regions of necrosis and/or purulence can indicate a potential infectious etiology

- Masses or other malignancy present in the brain/brainstem

Image: (Left) Transcranial herniation through right craniectomy site. (Right) Fixed brain with similar transcranial herniation; i.e., “fungus cerebri”. (Image credit: Desiree Marshall/King County Medical Examiner’s Office).

Image: (Left) Transcranial herniation through right craniectomy site. (Right) Fixed brain with similar transcranial herniation; i.e., “fungus cerebri”. (Image credit: Desiree Marshall/King County Medical Examiner’s Office).

Quick Tips at Time of Histology Evaluation

- Hernations do not need to be sampled for histology for confirmation. However, when the diagnosis is not clear, then histology can support the diagnosis

- The herniated tissue will show variable changes such as disruption, ischemia/necrosis, and hemorrhage. Punctate hemorrhage are characteristic.

- Findings for associated conditions such as meningeal bleeds or stroke/infarct (including hypoxic encephalopathy and brain death) are found in their respective articles. Tumors, infection/inflammation, and other findings related to the etiology can also be present.

Image: The above H&E stained slide contains hippocampus (center of the image) and parahippocampal tissues. There is patchy punctate hemorrhages throughout these tissues consistent with grossly observed left uncal and central downward brainstem herniation. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/Stanford Hospital).

Image: The above H&E stained slide contains hippocampus (center of the image) and parahippocampal tissues. There is patchy punctate hemorrhages throughout these tissues consistent with grossly observed left uncal and central downward brainstem herniation. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/Stanford Hospital).

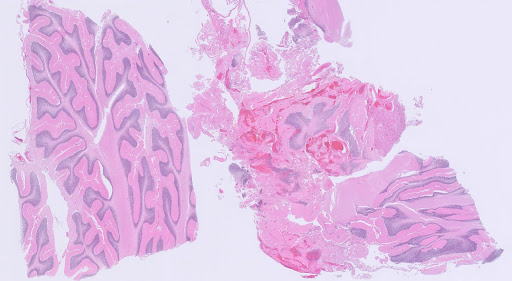

Image: This slide demonstrates intact/unherniated cerebellum on the left, and herniated cerebellum on the right. The herniated cerebellum demonstrates tissue architecture disruption and hemorrhage. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/Stanford Hospital).

Image: This slide demonstrates intact/unherniated cerebellum on the left, and herniated cerebellum on the right. The herniated cerebellum demonstrates tissue architecture disruption and hemorrhage. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/Stanford Hospital).

Image: High power of the same cerebellum shown above demonstrates eosinophilic purkinje cells that have lost their nucleoli consistent with ischemic changes. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/Stanford Hospital).

Image: High power of the same cerebellum shown above demonstrates eosinophilic purkinje cells that have lost their nucleoli consistent with ischemic changes. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/Stanford Hospital).

Quick Tips at Time of Reporting

- Herniations are secondary changes due to a primary process; they are seen in the setting of diffuse edema with or without hypoxic ischemic changes. When reporting, it is important to designate which areas are herniating and the underlying cause.

- Depending on the etiology, that can be listed as cause of death without commenting on brain herniation itself

- Ex. In the case of an epidural hemorrhage that caused transtentorial herniation, the cause of death could be listed as “Epidural hemorrhage due to blunt force trauma to the head from contact with a baseball bat.”

- Ex. Uncal herniation due to mass effect from a metastatic colorectal carcinoma in the brain.

- Occasionally, the underlying cause of the herniation is not possible to identify

- Ex. DIffuse edema with brain herniation due to unknown cause

Recommended References

- Leestma J. Forensic Aspects of Intracranial Equilibria. 2nd ed. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press; 2008.

- Maiese K. Brain Herniation. 2024. Brain Herniation – Neurologic Disorders – MSD Manual Professional Edition

Additional References

- Munakomi S., Das JM. Brain Herniation. Updated 2023. Treasure Island (FL): StatPears Publishing; 2024. Brain Herniation – StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf

- Knight J., Rayi A. Transtentorial Herniation. Updated 2023. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Transtentorial Herniation – StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf\

- Iwasaki Y. Brain cutting and trimming. Neuropathology. 2022; 42: 343-352.

- Gogia B., Bhardawj A. Duret Hemorrhages. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Duret Hemorrhages – StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf

- Ropper A., Samuels MA., Klein JP., Prasad S. Adams and Victor’s Principles of Neurology. 12th ed. New York City (NY): McGraw Hill/Medical; 2023.

- Johnson PL., Eckard DA., Chason DP., Brecheisen MA., Batnizky SB. Imaging of acquired cerebral herniations. Neuroimaging Clinics of North America. 2002; 12(2): 217-228.