Alexandra Medeiros MD & John Walsh MD*

Background

Code blue is an emergent event that is initiated when a hospitalized patient goes into cardiac or respiratory arrest. During this event a team is activated to perform high quality cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) according to the advanced cardiopulmonary life support (ACLS) algorithm. Several studies have concluded that in-hospital CPR has a succession rate between 20-40% (out of hospital CPR is less effective and these cases are more likely to end up at the local medical examiner’s office). CPR consists of:

- Chest compression and breaths

- Drug therapy intervention (epinephrine, amiodarone, lidocaine)

- Advanced airways

- Defibrillation

Adult and pediatric ACLS pathways vary slightly, but do have the same major components as listed above.

There are two outcomes of CPR, return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) or death.

As each compression applies 100-125 lbs (45-57 kg) of force, patients who have received adequate CPR intervention will likely demonstrate physical injuries. In at least one study, 93.7% of autopsies with a history of recent CPR demonstrated CPR-related injuries at autopsy (Ihnát Rudinská 2016). It is an important component of the autopsy to separate these findings from non-iatrogenic pathologies related to the cause of death, and to document them accordingly. An extreme example of this distinction is present in children who received CPR; pediatric posterior rib fractures are considered highly suggestive of nonaccidental trauma (child abuse) but can be present in populations who have received CPR with the 2 finger technique.

Quick Tips at Time of Autopsy

Clinical History

- CPR attempts and EMS reports should be documented in the patient’s chart and reviewed by the examining pathologist to see the extent of resuscitation (i.e. how many rounds) and what interventions took place (advanced airway, defibrillation, etc).

- Of note, a higher number of injuries such as rib and sternal fractures are seen with active compression-decompression CPR compared to standard CPR (Baubin 1999). Active compression-decompression CPR uses a device – LUCAS – to actively decompress the chest and achieve better recoil.

- If ROSC was achieved, note how long the patient was alive before they were declared deceased; this can be useful in contextualizing other findings such as CPR related hemorrhage, or ischemic changes in the brain.

- Advanced age, female sex, and longer CPR duration are the main risk factors for CPR related injury in adults (Ram 2018).

- Pediatric cases can have different patterns of injury due both to their intrinsic biology (more flexible rib cage means less rib fractures) as well as different protocols for CPR administration. The following article focuses on adults, but this article by Collins et.al is a good introduction to CPR injuries in children.

External examination

Head and Neck

- Conjunctival or mucosal petechial hemorrhages

- Endotracheal tube placement; broken teeth or mucosal tears can be present due to traumatic tube placement.

- Of note, conjunctival petechiae associated with CPR can occur, however CPR is a less common cause of conjunctival petechiae than once thought (Maxeiner 2010).

Thorax

- Sternal abrasion, a circular red-brown and dry central abrasion over the sternum (~5 to 7 cm in diameter). If the patient has a prolonged interval of resuscitation prior to end of life then these abrasions can also include bruising.

Image: Centrally located pressure defects from chest compressions. The lower left image demonstrates the circular impressions made by the LUCAS device. The patient on the upper right also has large suture lines from organ/tissue donation. (Image credits: top photos Meagan Chambers/University of Washington, bottom photos Alexandra Medeiros/Augusta University.)

Image: Centrally located pressure defects from chest compressions. The lower left image demonstrates the circular impressions made by the LUCAS device. The patient on the upper right also has large suture lines from organ/tissue donation. (Image credits: top photos Meagan Chambers/University of Washington, bottom photos Alexandra Medeiros/Augusta University.)

- Confirm proper placement of defibrillator pads.

- A single defibrillation shock can range from 120-300 joules and can produce skin erythema or superficial burns.

Image: Burn marks from a defibrillator pad. (Image credit: Reinhard Dettmeyer et.al in Forensic Medicine: The External Postmortem Exam).

Image: Burn marks from a defibrillator pad. (Image credit: Reinhard Dettmeyer et.al in Forensic Medicine: The External Postmortem Exam).

- If defibrillator pads are removed prior to the autopsy then rectangle shaped hair loss in characteristic locations can also suggest defibrillation.

Image: Proper placement of AED pads. Adults should have pads on the anterior right chest and anterolateral right thorax below the heart. Smaller children should have pads placed on the anterior central chest and posterior central back. (Image credit: Australia Wide First Aide).

Image: Proper placement of AED pads. Adults should have pads on the anterior right chest and anterolateral right thorax below the heart. Smaller children should have pads placed on the anterior central chest and posterior central back. (Image credit: Australia Wide First Aide).

Extremities

- Intraosseous and intravenous access [See the Implantable Medical Devices article.]

- Intraosseus access allows for rapid infusions of medications and fluids. They can be placed at the proximal tibia, humeral head or sternum in adults.

- Intravascular access is preferred, especially if the patient already has an established site either peripherally or centrally.

- Multiple needle puncture wounds may be noted attempts to gain vascular access

Internal examination

Bone fractures

- Sternal body fracture. The manubrium is fractured less frequently.

- Bilateral rib fractures along the mid-clavicular line are very common, especially the 2nd to 7th ribs. At least one randomized control trial found that standard CPR broke a mean of 8 ribs, and that broken ribs caused additional intrathoracic injuries in ~50% of cases (Ihnát Rudinská 2016).

- Elderly patients with reduced bone density are at the highest risk for fractures, which may affect the cervical or thoracic spine.

- Cervical spine injuries are also possible, although they are easily missed without special dissection techniques such as a posterior neck dissection.

Heart

- Localized mediastinal hemorrhage associated with rib fractures and other CPR-related trauma

- Pericardial sac puncture and hemopericardium, also secondary to rib fractures

- Epicardial and myocardial hemorrhage and bruising

- More often localized to the right ventricle due to anterior position in the body

- Subendocardial hemorrhage can be a notable finding after administration of catecholamines (see the histology section for more information).

- Subendocardial infarction can be seen in patients that achieved ROSC but then subsequently passed some time after CPR. The infarction becomes visible at autopsy because of life support long enough for structural myocardial changes to develop. Findings are most common in the left ventricle. Subtle changes may be limited to focal changes in the papillary muscles or trabeculae. Findings in the right ventricle are not common.

- The gross findings of the coronary arteries (such as a small or large burden of atherosclerosis) and location of the infarct can help determine if it’s a CPR related reperfusion injury. Epicardial, patchy, and right ventricular ischemic changes support a non-CPR etiology.

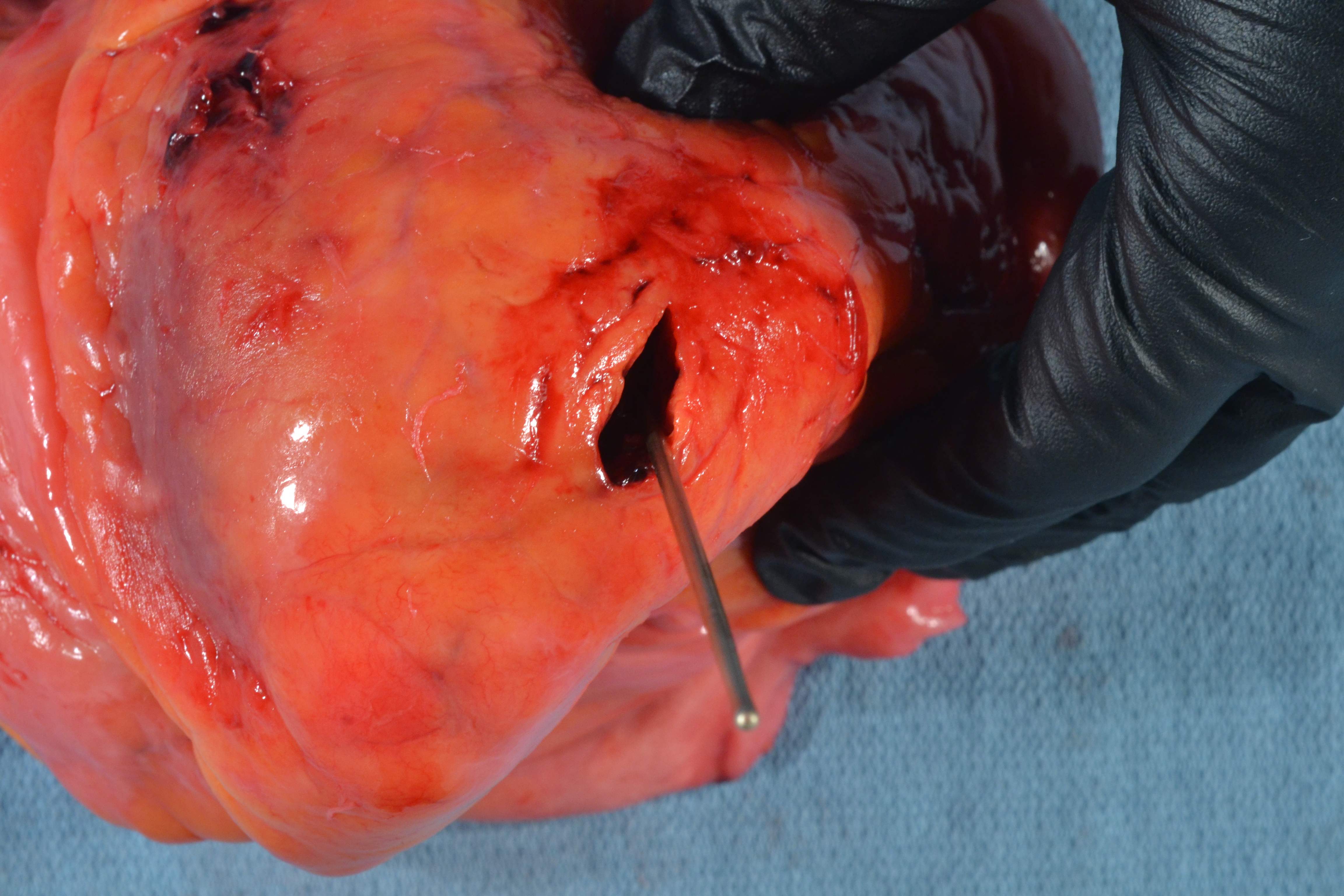

Images: An intraventricular laceration (top) and a transmural laceration (bottom) associated with CPR. Note in both cases the minimal extravasated hemorrhage consistent with perimortem laceration. (Image credits: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington.)

Images: An intraventricular laceration (top) and a transmural laceration (bottom) associated with CPR. Note in both cases the minimal extravasated hemorrhage consistent with perimortem laceration. (Image credits: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington.)

Lung and thorax:

- Hemothoraces may be a result of ruptured intercostal vessels, the great vessels, or internal mammary arteries.

- A pneumothorax can result from rib fractures introducing air into the pleural space or puncturing the lung.

- Pulmonary contusions result from direct damage (rib fractures or compressions) to the lung parenchyma.

Image: CPR-associated lung hemorrhage in the anterior aspect (circle). (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

Image: CPR-associated lung hemorrhage in the anterior aspect (circle). (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

- Aspiration: inhalation of stomach contents into the lungs, leading to aspiration pneumonia or chemical pneumonitis.

- Mucosal damage from intubation may be seen in cases where that is performed.

Image: Mucosal bleeding from intubation. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

Image: Mucosal bleeding from intubation. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

Abdomen

- The liver and spleen can be injured by displaced rib fragments or excessive compressive force, leading to lacerations or hematomas. The left lobe of the liver is most commonly affected due to its anatomical proximity to the sternum.

Image: Liver with left lobe lacerations. Note the lack of significant bleeding consistent with decreased perfusion at the time of CPR. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

Image: Liver with left lobe lacerations. Note the lack of significant bleeding consistent with decreased perfusion at the time of CPR. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

- Retroperitoneal bleeding can be seen secondary to lower rib fractures.

- Adults with intervention with the LUCAS device have increased risk for significant paraspinal hemorrhage (Azeli 2019).

Image: Paraspinal hemorrhage in the setting of LUCAS-assisted CPR. (Image credit: Shared with permission by the Armed Forces Medical Examiner System).

Image: Paraspinal hemorrhage in the setting of LUCAS-assisted CPR. (Image credit: Shared with permission by the Armed Forces Medical Examiner System).

Quick Tips at Time of Histology Evaluation

- Hemorrhage into lacerated tissues can be seen. If ROSC was not achieved, this hemorrhage should be fresh without significant organization or accumulation of extravasated inflammatory cells.

Images: Diffuse intraparenchymal cardiac (left) and pulmonary (right) hemorrhage associated with CPR. (Image credits: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington.)

- In cases where ROSC was successful but the patient subsequently passes away, ischemic-like changes may be present in various organs.

- In the heart resuscitation-related ischemia can mimic the early findings of a myocardial infarction.

- Contraction band necrosis and subendocardial hemorrhage associated with ischemic damage is more common after catecholamine administration. Catecholamines increase the influx of calcium into cardiac muscle cells. This leads to hypercontraction of the myofibrils, which is characteristic of contraction band necrosis. They also cause direct damage to the endothelial cells lining the coronary arteries, contributing to microvascular injury and hemorrhage, especially in areas already prone to ischemia such as the subendocardium.

- In the presence of rib fractures, bone marrow and/or fat emboli may be seen even at distant locations.

- Aspirated oropharyngeal contents can be found in lung sections. When trying to differentiate CPR/perimortem aspiration vs. antemortem aspiration, an associated inflammatory reaction is helpful and supports a true ante-mortem aspiration event.

- Diffuse edema in the lungs is a finding associated with CPR. It can also be seen in cases without CPR who received aggressive fluid resuscitation prior to death.

- If taken, the eyes may demonstrate CPR-related suprachoroidal hemorrhages.

Image: This patient who received CPR has both intra-alveolar hemorrhage and edema without any other significant histologic findings. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/Stanford University).

Image: This patient who received CPR has both intra-alveolar hemorrhage and edema without any other significant histologic findings. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/Stanford University).

Quick Tips at Time of Reporting

- The inciting event that leads to cardiac or pulmonary arrest, is the patient’s cause of death. It is important to avoid mechanisms in the cause of death statement such as cardiac arrest, cardiopulmonary failure, etc.

- As previously mentioned, CPR is rarely the sole contributor to cause of death, however if ROSC is achieved, the complications from CPR can contribute to the patient’s demise. In at least one study, life-threatening complications of CPR, such as heart and great vessel injuries, occurred in less than .5 percent of the cases (Krischer 1987).

- Sequelae of CPR can be listed in the report as additional findings, as below.

- Serious rib cage damage has been defined as a sternal fracture and/or > six unilateral rib fractures and/or > four rib fractures if one of them is bilateral (Koster 2017).

Clinical Tidbits

- The use of mechanical compressors, such as LUCAS, has become widespread, but this has not led to improved survival from cardiac arrest, and several studies have described an increased incidence of serious thoracic injuries (STIs) including paraspinal hemorrhage after their use (Azeli 2019).

Recommended References

- Deliliga, A., Chatzinikolaou, F., Koutsoukis, D., Chrysovergis, I., & Voultsos, P. (2019). Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) complications encountered in forensic autopsy cases. BMC Emergency Medicine, 19(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12873-019-0234-5

- Buschmann, C. T., & Tsokos, M. (2008). Frequent and rare complications of resuscitation attempts. Intensive Care Medicine, 35(3), 397–404. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-008-1255-9

Additional References

- Azeli Y, Lorente Olazabal JV, Monge García MI, Bardají A. Understanding the Adverse Hemodynamic Effects of Serious Thoracic Injuries During Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation: A Review and Approach Based on the Campbell Diagram. Front Physiol. 2019 Dec 3;10:1475. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.01475. PMID: 31849717; PMCID: PMC6901598.

- Ihnát Rudinská, L., Hejna, P., Ihnát, P., Tomášková, H., Smatanová, M., and Dvořáček, I. (2016). Intra-thoracic injuries associated with cardiopulmonary resuscitation – frequent and serious. Resuscitation 103, 66–70. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2016.04.002

- Kang DH, Kim J, Rhee JE, Kim T, Kim K, Jo YH, Lee JH, Lee JH, Kim YJ, Hwang SS. The risk factors and prognostic implication of acute pulmonary edema in resuscitated cardiac arrest patients. Clin Exp Emerg Med. 2015 Jun 30;2(2):110-116. doi: 10.15441/ceem.14.016. PMID: 27752581; PMCID: PMC5052861.

- Koster, R. W., Beenen, L. F., van der Boom, E. B., Spijkerboer, A. M., Tepaske, R., van der Wal, A. C., et al. (2017). Safety of mechanical chest compression devices AutoPulse and LUCAS in cardiac arrest: a randomized clinical trial for non-inferiority. Eur. Heart J. 38, 3006–3013. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx318

- Krischer JP, Fine EG, Davis JH, Nagel EL. Complications of cardiac resuscitation. Chest. 1987 Aug;92(2):287-91. doi: 10.1378/chest.92.2.287. PMID: 3608599.

- Maxeiner, H., and R. Jekat. “Resuscitation and Conjunctival Petechial Hemorrhages.” Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine, vol. 17, no. 2, Feb. 2010, pp. 87–91, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jflm.2009.09.010.

- Michaud K, Basso C, d'Amati G, Giordano C, Kholová I, Preston SD, Rizzo S, Sabatasso S, Sheppard MN, Vink A, van der Wal AC; Association for European Cardiovascular Pathology (AECVP). Diagnosis of myocardial infarction at autopsy: AECVP reappraisal in the light of the current clinical classification. Virchows Arch. 2020 Feb;476(2):179-194. doi: 10.1007/s00428-019-02662-1. Epub 2019 Sep 14. PMID: 31522288; PMCID: PMC7028821.

- Oshima T, Yoshikawa H, Ohtani M, Mimasaka S. Three cases of suprachoroidal hemorrhage associated with chest compression or asphyxiation and detected using postmortem computed tomography. Leg Med (Tokyo). 2015 May;17(3):188-91. doi: 10.1016/j.legalmed.2014.12.003. Epub 2014 Dec 12. PMID: 25533924.

- Ram, P., Menezes, R. G., Sirinvaravong, N., Luis, S. A., Hussain, S. A., Madadin, M., et al. (2018). Breaking your heart—a review on CPR-related injuries. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 36, 838–842. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2017.12.063

- Yamaguchi, R., Makino, Y., Chiba, F., Torimitsu, S., Yajima, D., Inokuchi, G., Motomura, A., Hashimoto, M., Hoshioka, Y., Shinozaki, T., & Iwase, H. (2017). Frequency and influencing factors of cardiopulmonary resuscitation-related injuries during implementation of the American Heart Association 2010 Guidelines: A retrospective study based on autopsy and Postmortem Computed Tomography. International Journal of Legal Medicine, 131(6), 1655–1663. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00414-017-1673-8

*The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Navy, Armed Forces Medical Examiner System, Uniformed Services University of Health Science, DHA, Department of Defense, or the US Government. The authors report no conflict of interest or sources of funding.