Authors: Meagan Chambers MD & Harry Sanchez MD

Background

Chronic obstructive airway disease (COPD) represents a spectrum of airway diseases including emphysema, chronic bronchitis, and asthma. It is characterized by airflow limitations. It is a top 10 cause of death in the United States.

This article includes findings associated primarily with emphysema and chronic bronchitis.

Quick Tips at Time of Autopsy

Clinical history

- Check the clinical history for the underlying cause:

- Smoking is the most common cause, but other inhaled irritants (industrial particulates, agricultural dusts, biomass fuel) have also been implicated.

- Genetic alterations in alpha-1-antitrypsin are common in cases with an early onset and genetic testing results may be present in the health record. (The median age at presentation for alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency is 46 years old).

- Not all patients will have an existing diagnosis of COPD, and it is a common new diagnosis at autopsy. (20% of pathologically proven cases show negative CT scans).

External examination

There are many external examination findings that can be associated with a diagnosis of COPD:

- “Pink puffer” – the classic physique in emphysema is a thin/emaciated patient with a large/barrel shaped chest due to air trapping (pulmonary hyperinflation). In contrast, those with chronic bronchitis are the “blue bloater” with excess weight gain.

- The accessory muscles of respiration and the Angle of Louis can be prominent (see images below).

Images: (Top) increased accessory respiratory muscles and (Bottom) increased Angle of Louis. (Image Credit: [Top] Loyola University Medical Education Network and [Bottom] UC San Diego Practical Guide to Clinical Medicine).

- Cyanosis (but usually not clubbing)

- Edema in those with right heart failure

- Yellow discoloration of fingertips in active smokers

- Calluses on elbows, forearms, or thighs from tripod posture (leaning forward with elbows on thighs)

Image: Dahl’s sign – calluses/hyperpigmentation from a tripod posture. (Image credits: (Above) Elliot Miller. Dahl’s Sign, (Below) Gabriel Rebick 2008)

Image: Dahl’s sign – calluses/hyperpigmentation from a tripod posture. (Image credits: (Above) Elliot Miller. Dahl’s Sign, (Below) Gabriel Rebick 2008)

- Skin changes such as thinning and bruising from chronic steroids

- Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency is associated with dermatologic manifestations. The most common is necrotizing panniculitis, followed less commonly by systemic vasculitis, psoriasis, urticaria, and angioedema.

Internal examination

- Before opening: checking for a pneumothorax prior to opening the chest cavity can be useful in COPD cases as pneumothorax are common with COPD (esp. emphysema), can trigger exacerbations, and can be part of the cause of death. Checking for a pneumothorax at autopsy is a special dissection technique which is described here.

- The chest cavity: hyperinflation can enlarge the lungs and obscure the heart when viewing the chest cavity.

- Lung/airway gross examination:

- The bronchi/large airways in chronic bronchitis patients may show boggy mucosa with excessive mucinous secretions and prominent mucosal pits overlying the orifices of bronchial mucous glands.

- The lung parenchyma in emphysematous patients will show variably sized cystic air spaces.

- Evidence of smoking may include increased anthracotic pigment deposition in lung parenchyma and mediastinal nodes.

- Sections: routine lung sections should include apical and basal lung parenchyma, as well as bronchial wall and associated vasculature.

Image: In situ view of the thoracic cavity. Diffuse deposition of anthracotic pigment can be seen bilaterally in the lungs of a smoker. Large bullae can also be observed bilaterally. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

Image: In situ view of the thoracic cavity. Diffuse deposition of anthracotic pigment can be seen bilaterally in the lungs of a smoker. Large bullae can also be observed bilaterally. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

- Heart gross examination: the heart may show changes associated with cor pulmonale (such as right ventricular hypertrophy).

- Right heart failure will in turn demonstrate findings of hepatosplenomegaly, nutmeg liver/centrilobular congestion, and/or ascites.

- Findings of pulmonary hypertension (from right heart failure) include yellow atherosclerotic plagued in large pulmonary arteries

- Gross exam findings in genetic cases of COPD (alpha-1-antitrypsin).

- Liver disease is common in cases of alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, which should be worked up based on routine liver section(s) at autopsy. Since liver disease can include hepatocellular carcinoma, close inspection for an undiagnosed malignancy is also warranted.

- Vascular pathology is also increased in AAT including abdominal and intracranial aneurysms, arterial fibromuscular dysplasia, and venous thromboembolism (VTE).

Ancillary testing

- If tested, pre-mortem or ante-mortem blood samples may show polycythemia, increased hemoglobin, and increased hematocrit in chronically hypoxic patients.

Quick Tips at Time of Histology Evaluation

- Bronchial sections in chronic bronchitis

- Early changes include hypertrophy of submucosal glands in the tracheobronchial tree while later changes include increased goblet cells in small airways.

- The Reid Index (see illustration below) can be used to measure the percentage of bronchial wall occupied by submucosal mucous glands. This directly correlates with sputum production, variable dysplasia, squamous metaplasia, and bronchiolitis obliterans. (Of note, the Reid Index is useful in emphysema, chronic bronchitis, and asthma). <0.4 is a normal Reid Index.

- Chronic inflammatory infiltrates are variable.

- Early changes include hypertrophy of submucosal glands in the tracheobronchial tree while later changes include increased goblet cells in small airways.

- Peri-bronchial vessels can be enlarged.

Image: How to calculate the Reid Index in bronchial histology. Image Credit: Andrew Binks, COPD in Pulmonary Pathophysiology,available online at LibreTexts Medicine).

- Lung parenchyma sections in emphysema

- Sections demonstrate enlarged airspaces, irregular acini, and thin septae with nodular “club-like” tips.

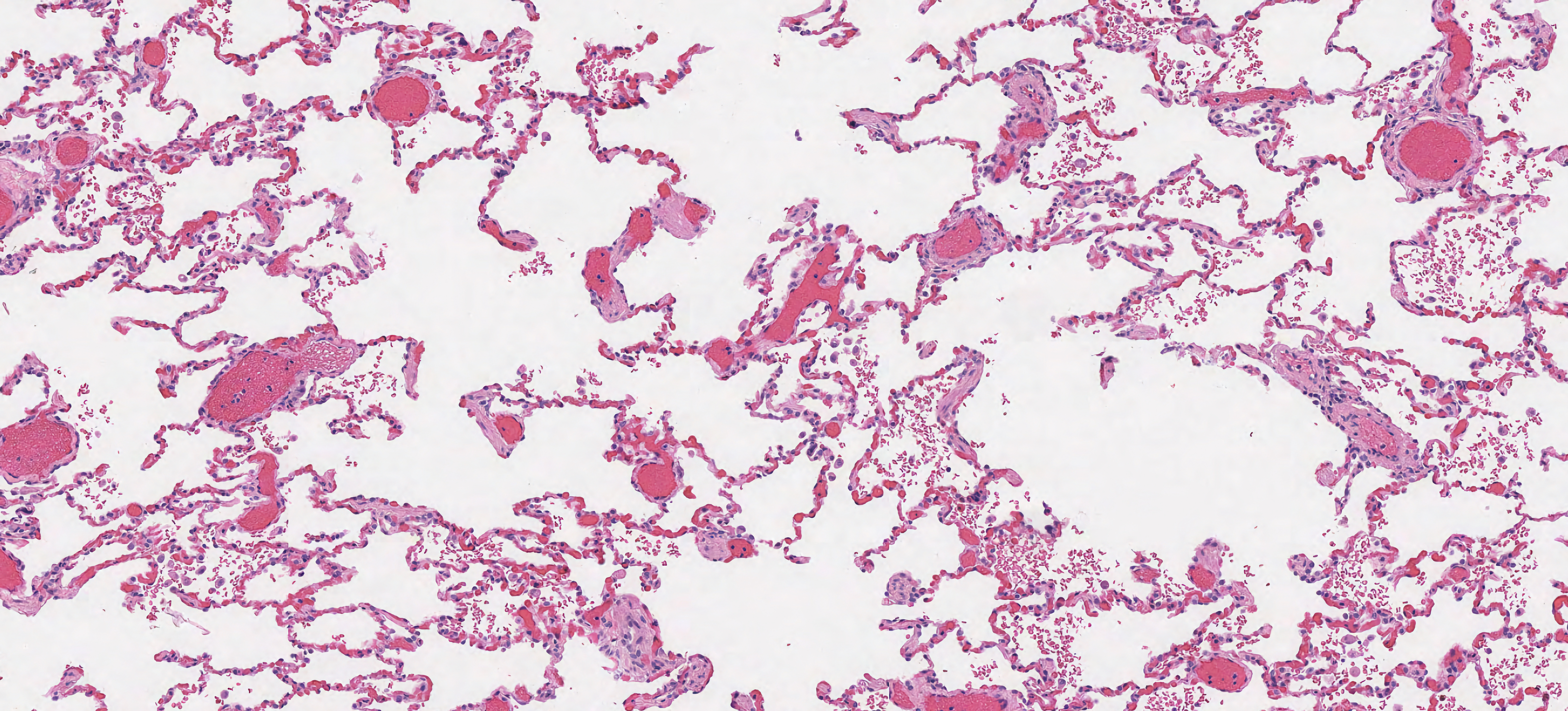

Image: Histology of emphysema with enlarged airspaces, thin alveolar septa, and club-shaped alveolar septa. (Image credit: University of Singapore).

Image: Histology of emphysema with enlarged airspaces, thin alveolar septa, and club-shaped alveolar septa. (Image credit: University of Singapore).

Image: close up of disrupted airspaces with clubbing. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/Stanford University).

Image: close up of disrupted airspaces with clubbing. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/Stanford University).

- There are three patterns of emphysema

|

Pattern |

Location |

Histology |

Etiology |

|

Centriacinar |

lung apex |

terminal bronchiole disease with sparing of peripheral respiratory lobule |

smoking |

|

Panacinar |

lung base |

the entire respiratory lobule is involved |

alpha-1 antitrypsin |

|

Paraseptal |

subpleural, esp. fissures |

- Fibrosis and inflammation are usually minimal but can be seen focally. (Of note, chronic inflammation in the lungs can be underlying cause of emphysematous changes).

- In smokers, intraalveolar pigmented macrophages (“smoker’s macrophages”) and increased anthracotic pigment deposition can be seen.

- Genetic cases

- Accumulation of altered alpha-1 antitrypsin in hepatocytes will stain with PAS.

- Liver disease can also include chronic hepatitis, cholestasis, cholangitis, cirrhosis, and/or hepatocellular carcinoma.

Images: (Left) Distribution of centriacinar emphysema. Photograph of an inflated and fixed lung showing emphysematous foci with anthracosis mainly distributed in the upper lobe and superior segment of the lower lobe (*). (Right) Panacinar emphysema. An inflated-fixed lung does not demonstrate obvious anthracosis. Enlargements of airspaces are diffusely observed and in some areas the disease is bordered by the interlobular septum (arrow). (Bottom) Distal acinar emphysema. Photograph of an inflated and fixed lung specimen showing subpleural airspaces with smooth wall structures. (Image credits: Akira Yoshikawa et. al., Obstructive pulmonary disease: Emphysema on PathOutlines).

Quick Tips for Autopsy Report

- The sub-classification of emphysema can be challenging with multiple recognized subtypes including combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema, interstitial emphysema, bullous emphysema, senile emphysema, irregular emphysema, and congenital lobar emphysema. Atypical presentations or unusual histologic findings may be the key to exploring one of these less common/incidental manifestations of emphysema.

- Example cause of death statements:

- “Hypoxic respiratory failure due to pulmonary emphysema. Contributing conditions: smoking, chronic bronchitis.” Here, emphysema and chronic bronchitis are both present in the same patient, but one is considered “primary” and is included in the cause of death line while the other is a more minor component and is recognized in the contributing conditions.

- “Pulmonary emphysema.” This is a simplified format which drops the mechanism of death. Of note, even in a simplified format it is good to keep the location (“pulmonary”) since emphysema itself is not specific to any one location in the body, even though by convention we usually mean pulmonary emphysema.

- “Spontaneous pneumothorax, due to rupture of bulla, due to pleural bleb, due to pulmonary emphysema.”

- “Streptococcus pneumoniae due to pulmonary emphysema.”

Recommended References

- Stoller J. Extrapulmonary manifestations of alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. UpToDate. Accessed 2023.

- Weisenberg E. Obstructive pulmonary disease: chronic bronchitis. Accessed 2023.

Additional References

- Ahmad FB, Cisewski JA, Xu J, Anderson RN. Provisional Mortality Data — United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2023;72:488–492. DOI

- Fetttal N, Taleb A. Pneumothorax secondary to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. European Respiratory Journal Sep 2012, 40 (Suppl 56) P558

- Takizawa T, Thurlbeck WM. Muscle and mucous gland size in the major bronchi of patients with chronic bronchitis, asthma, and asthmatic bronchitis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1971 Sep;104(3):331-6. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1971.104.3.331. PMID: 5098669