Nadia S. Siddiqui & Desiree Marshall MD

Background

Epidural hemorrhage (EDH), subdural hemorrhage (SDH), and subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) are intracranial bleeds at varying anatomic locations

- EDH

- An arterial bleed between the skull and dura.

- Most commonly due to injury to the middle meningeal artery.

- SDH

- Venous bleeds between the dura and the brain.

- Can be acute or acute on chronic with episodes of longitudinal rebleeding

- SAH

- Arterial or venous bleeds at the brain surface (within the leptomeninges)

- Can also occur from rupture of aneurysm or arteriovenous malformation

Image: Illustration of the typical locations for intracranial bleeds. (Image source: Wikkimedia Commons).

Image: Illustration of the typical locations for intracranial bleeds. (Image source: Wikkimedia Commons).

Image: Subarachnoid bleeds occur in the leptomeninges, between the arachnoid and the pia. (Image credit: Stony Brook Medicine).

Image: Subarachnoid bleeds occur in the leptomeninges, between the arachnoid and the pia. (Image credit: Stony Brook Medicine).

Quick Tips at Time of Autopsy

Clinical History

Table 1: Clinical history and radiographic findings of CNS bleeds

| EDH |

|

| SDH |

|

| SAH |

|

Table 2: Risk factors for EDH, SDH, and SAH

| EDH |

|

| SDH |

|

| SAH |

|

- Antemortem data in the medical record

- Glasgow coma scale

- A lumbar puncture can show blood

- Diagnoses or lab results confirming risk factors for coagulopathy (CBC, platelet count, PT, PTT, INR, D-dimer, also hereditary causes of coagulopathy)

- Surgical history, especially interventions involving the skull/dura (such as surgical evacuation/decompression)

External examination

- Evidence of head trauma

- Lacerations, contusions, etc. should be carefully documented including location, size, and accurate descriptions (e.g. “laceration” vs. “incision”).

- Bruising over the mastoid process is concerning for a basilar skull fracture with associated epidural bleeding (“Battle sign”). This may or may not be accompanied by blood leaking from the ears.

- Periorbital bruising (bilateral black eyes) is also associated with epidural or subdural bleeding in the setting of a basilar skull fracture.

- Evidence of surgical intervention associated with decompression of the bleed; these can be recent or old depending on the clinical history.

- Burr hole

- Healing craniotomy/hemicraniectomy site best seen from inside of skull

- Catheters, VP-shunt tube

- Surgical clips, coils, stents, and sponge-materials

Image: Prior craniotomy site with subsequent replacement of the patient’s native bone. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

Image: Prior craniotomy site with subsequent replacement of the patient’s native bone. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

- Evidence of non-head trauma can also be present elsewhere on the body and should be documented as per usual.

Ancillary Testing

- Radiology should be performed in the case of penetrating or perforating injuries to the neck to assess for air emboli prior to opening the body.

Internal examination

- For all bleeds, sampling the margin of the bleed is recommended in order to see a broader spectrum of histologic findings related to dating the bleed.

- Skull fractures indicate significant impact to the head (sufficient to break the bone).

- Subgaleal blood or hematomas may be present in association with head trauma.

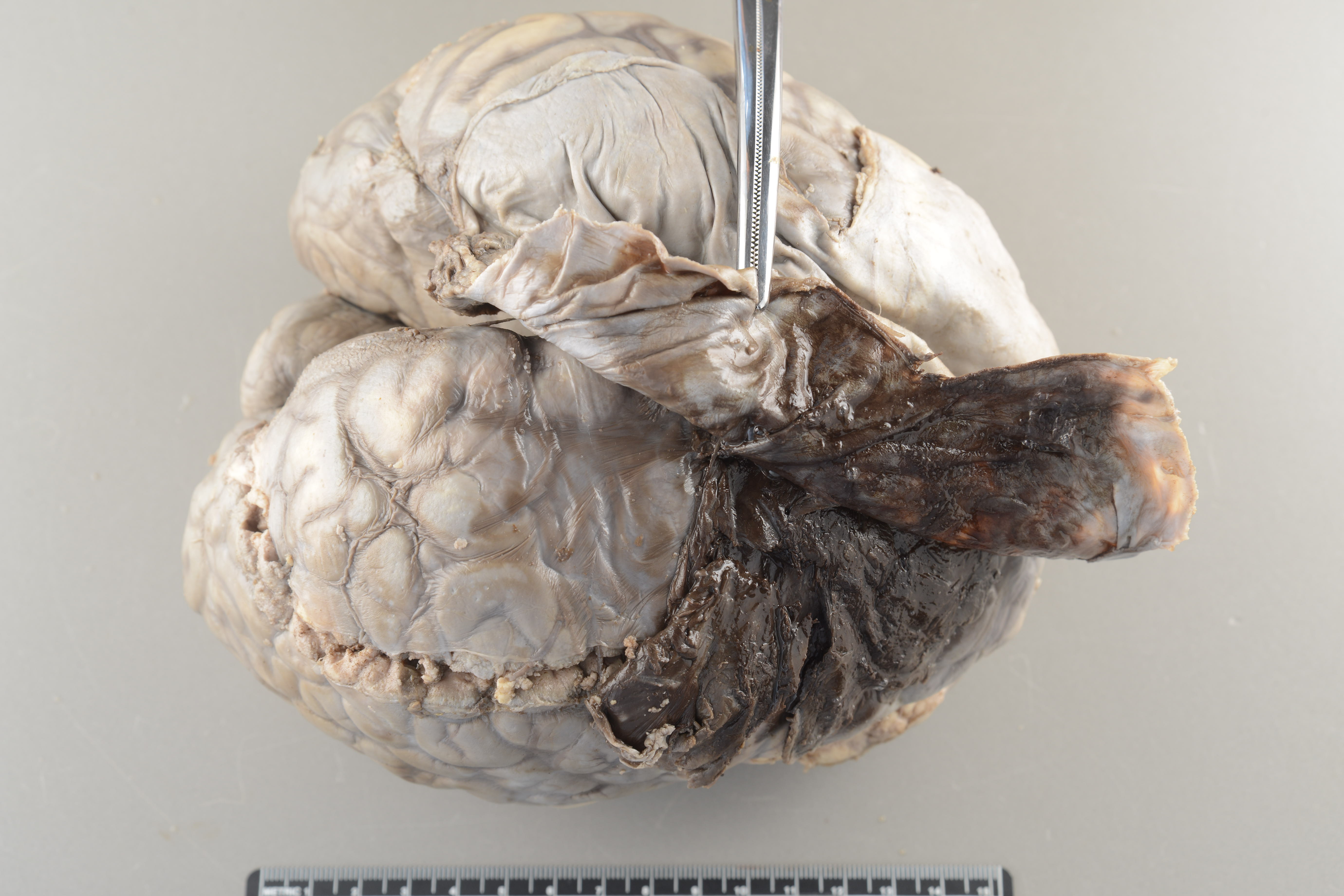

Image: Subgaleal bleeds at autopsy. (Image credit: Desiree Marshall/King County Medical Examiner’s Office).

Image: Subgaleal bleeds at autopsy. (Image credit: Desiree Marshall/King County Medical Examiner’s Office).

Table 3: Gross examination findings in EDH, SDH, SAH

| EDH |

|

| SDH |

|

| SAH |

|

Image: At autopsy, an acute subdural bleed will be visualized between the brain and the dura. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

Image: At autopsy, an acute subdural bleed will be visualized between the brain and the dura. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

Images: (Upper image) Here the brain and the dura have been fixed together. When the dura is retracted, residual blood is seen on the apposed surfaces of the dura and leptomeninges. (Lower image) On closer inspection bridging veins between the dura and the leptomeninges are seen (white arrow). (Image credit: Desiree Marshall/King County Medical Examiner’s Office).

Images: (Upper image) Here the brain and the dura have been fixed together. When the dura is retracted, residual blood is seen on the apposed surfaces of the dura and leptomeninges. (Lower image) On closer inspection bridging veins between the dura and the leptomeninges are seen (white arrow). (Image credit: Desiree Marshall/King County Medical Examiner’s Office).

Image: A subacute SDH shows thicker areas of organizing hemorrhage (red arrow) with thinner more golden neomembranes peripherally (yellow arrow). The way the neomembrane peels off the dura is also illustrated in areas where it has been disrupted (white arrow). (Image Source: Desiree Marshall/King County Medical Examiner’s Office).

Image: A subacute SDH shows thicker areas of organizing hemorrhage (red arrow) with thinner more golden neomembranes peripherally (yellow arrow). The way the neomembrane peels off the dura is also illustrated in areas where it has been disrupted (white arrow). (Image Source: Desiree Marshall/King County Medical Examiner’s Office).

Image: A neomembrane from a prior subdural bleed demonstrating their characteristic thin, golden-tinged appearance. (Image credit: Desiree Marshall/King County Medical Examiner’s Office).

Image: A neomembrane from a prior subdural bleed demonstrating their characteristic thin, golden-tinged appearance. (Image credit: Desiree Marshall/King County Medical Examiner’s Office).

Image: Subdural neomembrane demonstrating the characteristic way it peels up from the dura. Care should be taken as this only requires light traction and neomembranes can be easily lost with rough handling. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

Image: Subdural neomembrane demonstrating the characteristic way it peels up from the dura. Care should be taken as this only requires light traction and neomembranes can be easily lost with rough handling. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

- Neomembranes are not an uncommon autopsy finding and they can occur without a corresponding clinical history of a suspected brain bleed or known head trauma (especially with SDH as opposed to EDH), therefore it is important to look closely for this easy-to-miss but characteristic finding.

- It is important to measure the thickness of the neomembrane.

Image: At autopsy, a subarachnoid hemorrhage will appear as extravasated blood within the leptomeninges. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

Image: At autopsy, a subarachnoid hemorrhage will appear as extravasated blood within the leptomeninges. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

Image: On cross section, subarachnoid bleeds can be seen filling sulcal spaces. It is important to measure and record the thickest area of the SAH above the gyri (the small arrow in this cross section). (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

Image: On cross section, subarachnoid bleeds can be seen filling sulcal spaces. It is important to measure and record the thickest area of the SAH above the gyri (the small arrow in this cross section). (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

-

- To evaluate SAH microscopically, brain sections with overlying leptomeninges should be taken, avoiding separation of the cortex and the leptomeninges.

- If a ruptured aneurysm is suspected, vessel dissection should be done carefully to evaluate for malformation.

- After documentation, gently rinse away as much fresh blood prior to fixation. Fixed blood is more difficult to dissect off of the aneurysm.

- For an obscuring fixed blood clot, hydrogen peroxide can be used to clear the fixed blood to evaluate the vessels.

Image: (Left) Removed Circle of Willis and surrounding vasculature with arrow at the basilar artery for orientation. (Right) Schematic of Circle of Willis with most frequent locations of obstructive lesions and arrow at the basilar artery. (Image credit: (Left) Desiree Marshall/King County Medical Examiner’s Office. (Right) E&P’s Manual of Basic Neuropath, Chapter 4, pg 95.)

Image: (Left) Removed Circle of Willis and surrounding vasculature with arrow at the basilar artery for orientation. (Right) Schematic of Circle of Willis with most frequent locations of obstructive lesions and arrow at the basilar artery. (Image credit: (Left) Desiree Marshall/King County Medical Examiner’s Office. (Right) E&P’s Manual of Basic Neuropath, Chapter 4, pg 95.)

- Secondary gross findings from the bleed may include edema, herniation, etc.

Quick Tips at Time of Histology Evaluation

The histologic changes associated with meningeal brain bleeds follow principles similar to bleeds in other sites with a general timeline progressing from intact RBCs through granulation tissue to resolution which often leaves residual fibrosis and/or hemosiderin.

Table 4: Histologic changes associated with dating meningeal brain bleeds

| Time Interval | Histologic Findings | |

| Acute | Minutes to hours | Fresh blood, intact red blood cells (RBCs), intact fibrin and platelets, no significant inflammatory response |

| 12-24 hours | Red blood cell lysis begins, early infiltration of neutrophils, presence of hemophagocytic macrophages. Eosinophils can be present as well as Charcot-Leyden crystals. | |

| 2-3 days | Increased neutrophil infiltration, more prominent macrophages, beginning of fibroblast activity (activated fibroblasts at the dura-clot interface), early granulation tissue formation, early evidence of endothelial hypertrophy and proliferation. (If needed, organizing fibers will stain with reticulin stain). | |

| Evolving | 4-7 days | Dominance of macrophages with and without pigment (hemosiderin-laden macrophages), reduction in neutrophils(usually neutrophils are only present after 7 days if rebleeding has occurred), increased fibroblast proliferation, collagen deposition starts, early organization of the hematoma. Prominent RBC lysis around 4-5 days, with confluent lysis of red blood cells (“laking”) by around 7 days. |

| Subacute | 1-2 weeks | Continued collagen deposition, formation of new blood vessels (angiogenesis – generally indicates >10 days since bleeding, capillaries can have serpigenous profiles), decreased cellularity with persistence of hemosiderophages. In SDH, the thickness of the neomembrane is typically greatest at ~2-4 weeks with progressive thinning over time, depending on the size of the clot. Hematoidin peaks around 7-10 days. |

| 3-4 weeks | Dense collagen network, further reduction in cellularity, hemosiderin deposition, well-organized granulation tissue. RBCs will be completely lysed by this time period. | |

| Chronic | 1-3 months | Mature scar tissue, significant collagen, few residual macrophages, hemosiderin persists. Often a time where secondary hemorrhages may be present. |

| 3-6 months | Well-formed scar tissue, minimal cellular activity, presence of hemosiderin and fibrous tissue | |

| 6 months to 1 year | Structures are replaced by collagenized connective tissue (seen with Masson’s trichrome), some capillaries may persist. Stable histologic appearance, hemosiderin may still be present. | |

| 1-2 years | Rare pigment-laden macrophages may be present. In SDH the neomembrane will be thin and can be difficult to distinguish from native dura. Orientation of collagen fibers can be helpful in differentiating between neomembrane and dura. | |

(Table credit: Adapted from Aromatario 2021, Sens 2024, and Rhodes 2024).

- It is important to note that the histologic timeline does not always match the clinical timeline. The timeline categories are not definitive (acute vs. recent, chronic vs. remote) and exist on a spectrum. Histologic dating is imprecise as we are evaluating biologic systems with variance, however pathologists are able to provide rough guidelines and general features.

- Also, evolution of SDH are better characterized in the literature compared to SAH and therefore dating an SAH is less reliable. (Consider categories such as acute, organizing, and chronic, rather than being more precise).

- Note that morphology of constituents of organizing hemorrhages can be bizarre and may be interpreted as neoplastic. Exercise caution in evaluating these, as a proliferative index (such as Ki-67) will be elevated in both cases.

- In SDH, the bleed is organized by leukocytes and fibroblasts migrating from the dura and so the progression of changes occurs from the inside (near the dura) out (farther from the dura). In the literature this is emphasized by drawing the distinction between an “inner” and “outer” membrane based on the different rates of organization. By some accounts, dural cells form the outer granulation tissue in 7-10 days and the inner neomembrane forms after 3 weeks. (Rhodes 2024).

Image: in an acute bleed, the RBC’s are not lysed. This can be better evaluated by engaging the condenser which will make the outlines of the RBCs stand out. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

Image: in an acute bleed, the RBC’s are not lysed. This can be better evaluated by engaging the condenser which will make the outlines of the RBCs stand out. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

- In the acute phase, it can be hard to distinguish a true antemortem bleed from postmortem bleeding. An iron stain will not stain fresh blood but will stain the iron lost from lysed RBCs and therefore a positive stain would support a true, acute, premortem bleed.

Image: Acute SAH with RBC lysis (confluent lysis is referred to as “laking”) – this dates the bleed to under 7 days prior to death. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

Image: Acute SAH with RBC lysis (confluent lysis is referred to as “laking”) – this dates the bleed to under 7 days prior to death. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

Image: SAH with polymorphonuclear infiltrate including many macs. Adjacent brain can be seen at the left and right lower corners. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

Image: SAH with polymorphonuclear infiltrate including many macs. Adjacent brain can be seen at the left and right lower corners. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

Image: A macrophage rich infiltrate is seen migrating from the dura (left image – right side of the photo) into the neomembrane which also contains abundant macrophages (left side of the photo). A corresponding stain for macrophages in this non-autopsy case confirms the abundant macrophages (right). (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

Image: A macrophage rich infiltrate is seen migrating from the dura (left image – right side of the photo) into the neomembrane which also contains abundant macrophages (left side of the photo). A corresponding stain for macrophages in this non-autopsy case confirms the abundant macrophages (right). (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

Image: This SDH demonstrates a preponderance of fibroblasts, with organization beginning at the periphery of the bleed (right side of the image). Small vessels and fresh blood are suggestive of re-bleeding.

Image: This SDH demonstrates a preponderance of fibroblasts, with organization beginning at the periphery of the bleed (right side of the image). Small vessels and fresh blood are suggestive of re-bleeding.

Image: A chronic neomembrane demonstrates thin, wispy collagen fibers with scattered hemosiderin. The native dura can be seen at the top right hand corner of the image. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

Image: A chronic neomembrane demonstrates thin, wispy collagen fibers with scattered hemosiderin. The native dura can be seen at the top right hand corner of the image. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

- The vessels associated with granulation tissue and long term organization are typically thin-walled and fragile. Therefore, new bleeds within the neomembrane are not uncommon.

Image: in this chronic neomembrane there are both hemosiderin laden macrophages (red circle) and a hematoidin laden macrophage (white circle), this is not uncommon as the vessels in neomembranes are thin and prone to rebleeding. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

Image: in this chronic neomembrane there are both hemosiderin laden macrophages (red circle) and a hematoidin laden macrophage (white circle), this is not uncommon as the vessels in neomembranes are thin and prone to rebleeding. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

Quick Tips at Time of Reporting

Example causes of death:

- Epidural hemorrhage due to head trauma from baseball bat contact with head

- Subdural hemorrhage due to ground-level fall, secondary to age-related brain atrophy

- Subarachnoid hemorrhage due to ruptured saccular aneurysm

- Of note, epidural bleeds often result from localized trauma at the site of the bleed. SDH is typically a non-localized process. SAH can be localized, as with an underlying contusion. But SAH can also be a marker of diffuse damage in that the bleed itself can be located at a site unrelated to the area of trauma.

Recommended References

- Aromatario M, Torsello A, D’Errico S, Bertozzi G, Sessa F, Cipolloni L, Baldari B. Traumatic Epidural and Subdural Hematoma: Epidemiology, Outcome, and Dating. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021 Feb 1;57(2):125. doi: 10.3390/medicina57020125. PMID: 33535407; PMCID: PMC7912597.

- Mary Ann Sens, Mark A. Koponen, Rebecca A. Irvine. Trauma to Central Nervous System. ExpertPath. Accessed 2024. (ExpertPath Login Required)

- Roy H. Rhodes, David S. Premier. Subdural Hemorrhage. ExpertPath. Accessed 2024. (ExpertPath Login Required)

- Melike Pekmezci, B.K. Kleinschmidt-DeMasters. Subdural Hematoma. ExpertPath. Accessed 2024. (ExpertPath Login Required)

- Roy H. Rhodes, David S. Premier. Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. ExpertPath. Accessed 2024. (ExpertPath Login Required)

Additional References

- Rao MG, Singh D, Vashista RK, Sharma SK. Dating of Acute and Subacute Subdural Haemorrhage: A Histo-Pathological Study. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016 Jul;10(7):HC01-7. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/19783.8141. Epub 2016 Jul 1. PMID: 27630864; PMCID: PMC5020299.

- Delteil C, Kolopp M, Capuani C, Humez S, Boucekine M, Leonetti G, Torrents J, Tuchtan L, Piercecchi MD. Histological dating of subarachnoid hemorrhage and retinal hemorrhage in infants. Forensic Sci Int. 2019 Oct;303:109952. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2019.109952. Epub 2019 Sep 12. PMID: 31546166.

- Walter T, Meissner C, Oehmichen M. Pathomorphological staging of subdural hemorrhages: statistical analysis of posttraumatic histomorphological alterations. Leg Med (Tokyo). 2009 Apr;11 Suppl 1:S56-62. doi: 10.1016/j.legalmed.2009.01.112. Epub 2009 Mar 18. PMID: 19299189.

- Yamashima T. The inner membrane of chronic subdural hematomas: pathology and pathophysiology. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2000 Jul;11(3):413-24. PMID: 10918010.

- Catana D, Koziarz A, Cenic A, Nath S, Singh S, Almenawer SA, Kachur E. Subdural Hematoma Mimickers: A Systematic Review. World Neurosurg. 2016 Sep;93:73-80. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2016.05.084. Epub 2016 Jun 4. PMID: 27268313.

- Zeyu Zhang, Yuanjian Fang, Cameron Lenahan, Sheng Chen. The role of immune inflammation in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Exp Neurol. 2021 Feb;336:113535. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2020.113535. Epub 2020 Nov 27. PMID: 33249033.

- Lauzier DC, Athiraman U. Role of microglia after subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2024 Jun;44(6):841-856. doi: 10.1177/0271678X241237070. Epub 2024 Feb 28. PMID: 38415607.

- Zheng VZ, Wong GKC. Neuroinflammation responses after subarachnoid hemorrhage: A review. J Clin Neurosci. 2017 Aug;42:7-11. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2017.02.001. Epub 2017 Mar 13. PMID: 28302352.

- Hidehiro Takei. Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. ExpertPath. Accessed 2024. (ExpertPath Login Required)