Meagan Chambers MD & Kathryn Scherpelz MD

Background

Brain death is defined as the irreversible cessation of all cerebral and brainstem functions. It represents the clinical and legal determination of death, even if other bodily functions can be maintained artificially. Once a person is declared brain dead, they are legally and clinically dead.

The diagnosis of brain death requires:

- A known and irreversible cause of coma

- Absence of all cerebral activity and brainstem reflexes

- No spontaneous respirations (confirmed with an apnea test)

- +/- Ancillary tests

The pathophysiology of brain death can be understood in terms of the sequence of events leading to global cerebral ischemia, which ultimately results in the cessation of brain function:

- A brain injury leads to cytotoxic and vasogenic edema

- leads to → Increased intracranial pressure

- leads to → Decreased cerebral perfusion pressure and brain herniation (due to the rigidity of the skull)

- leads to → Global ischemia and irreversible neuronal damage and brain death

Brain death is a clinical term, and the associated histologic changes may vary based on the particular circumstances of the case. A related term “respirator brain” (“non-perfused brain”) is used to describe the shared gross and histologic findings which are found in a brain which lacks intracranial blood flow while a patient is maintained on a ventilator. Importantly, the categories of brain death and non-perfused brain are overlapping but not always the same (brain death can occur in the presence of some amount of perfusion).

Quick Tips at Time of Autopsy

Clinical History

Brain death is a clinical diagnosis which will be documented by the care team prior to autopsy.

- Knowing the interval from last detectable signs of brain function to when the life support is withdrawn (the brain death to cardiac arrest interval) is necessary to correlate with the gross and microscopic findings.

- It is important to consider two time intervals prior to interpreting the autopsy findings

- The interval from intracranial lesion to non-perfusion (e.g. the time for the lesion to evolve).

- The interval from declaration of brain death to life support withdrawal (e.g. time for autolysis).

- Prolonged ventilator use in patients with brain death typically will show decreased density on imaging due to edema and autolysis of the parenchyma (termed “ventilator injury”) due to enzymatic activity in the absence of cerebral perfusion.

External examination

- Evidence of medical intervention should be present including medical devices, which as a matter of policy should be left in place prior to the autopsy. (See: Evidence of Therapeutic Intervention).

- Evidence of organ donation may also be present and should be duly documented.

Internal examination

Findings

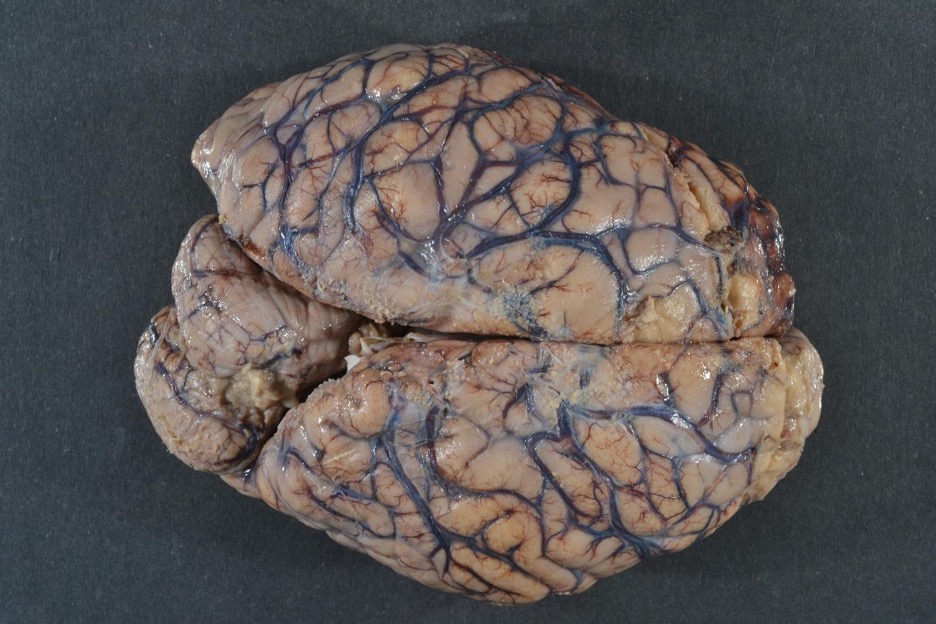

- Brain Swelling (flat gyri and narrow sulci) and herniation (translocation of tissue through or past rigid structures in the cranium) are commonly present. They are a result of edema from the initial injury and subsequent cell death (a combination of cytotoxic and/or vasogenic edema).

- Diffuse dusky or gray discoloration.

- Congested Blood Vessels, reflecting stasis of blood flow.

- Consistent with tissue death, the brain may remain soft despite adequate fixation.

Image: gross examination of the brain can show diffuse edema (swelling with effacement of sulci) and dusky discoloration. These findings are commonly seen in a respirator brain. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers, University of Washington).

Image: gross examination of the brain can show diffuse edema (swelling with effacement of sulci) and dusky discoloration. These findings are commonly seen in a respirator brain. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers, University of Washington).

- Additional evidence of increased intracranial pressure includes petechial hemorrhages and Duret hemorrhages in the presence of brain herniation.

Image: Duret hemorrhages. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers, University of Washington).

Image: Duret hemorrhages. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers, University of Washington).

Quick Tips at Time of Histology Evaluation

- Brain death most commonly occurs in the setting of cerebral non-perfusion. It is therefore primarily a process of autolysis rather than necrosis.

- The key histologic findings follow from this fundamental distinction and so a review of mechanisms of tissue degeneration in the brain is provided here

| Postmortem Tissues Changes in the Brain: | |

| Necrosis | Tissue death with eventual cell breakdown (coagulative or liquefactive) with reactive cell influx, phagocytosis, and eventual cavitation/glial scar formation |

| Autolysis | Breakdown of cells or tissues through the release and/or deregulated activation of endogenous proteolytic enzymes. Loss of nuclear details (nuclear chromatolysis). The end point depends on the conditions to which the tissue is exposed |

| Mummification | Dehydration (hot, dry environments) leads to preservation of tissue architecture |

| Maceration | Tissues dissolve in a wet environment (such as intrauterine demise) |

| Saponification

(adipocere) |

Hydrolysis and hydrogenation of fatty tissues in a warm, wet environment (classically a death by drowning) creating a waxy film |

| Putrefaction | Tissue breakdown by postmortem overgrowth of bacteria present in the body at time of death |

(Adapted from Folkerth 2023).

- Generally, there is not evidence of inflammatory infiltration (or subsequent tissue remodeling) as elevated intracranial pressure prevents cerebral perfusion and subsequent extravasation. Extravasated inflammatory cells and tissue remodeling are evidence of at least partial residual perfusion.

- The exception would be residual inflammation already present before loss of cerebral perfusion and/or adults with craniotomies which allow for release of some of the intracranial pressure such that perfusion is not lost.

- Another notable exception would be infants and small children with open fontanelles. In these cases, perfusion/inflammation co-occurring with brain death is more common because the open fontanelles accommodate the swelling and intracranial pressure does not exceed perfusion pressure.

Image: the brain of an infant maintained on life support for >2 weeks after brain death was declared. The tissue demonstrates extensive tissue loss and cavitation. This is only possible because of the open fontanelles allowed for brain swelling without loss of perfusion (due to the flexibility of the cranial structures) with subsequent inflammatory infiltrates and tissue remodeling. (Image credit: Shared with permission. Uncredited to protect patient’s identity).

Image: the brain of an infant maintained on life support for >2 weeks after brain death was declared. The tissue demonstrates extensive tissue loss and cavitation. This is only possible because of the open fontanelles allowed for brain swelling without loss of perfusion (due to the flexibility of the cranial structures) with subsequent inflammatory infiltrates and tissue remodeling. (Image credit: Shared with permission. Uncredited to protect patient’s identity).

- In brain death cases with a very long interval from brain death to removal on life support (months to years), there can be some superficial perfusion through external-to-internal carotid reperfusion wherein superficial cerebral and cerebellar cortices are perfused by neovessels branching from the middle meningeal artery.

- Look for extravasated inflammatory cells and tissue remodeling in the superficial cortex.

Image: Diagram of normal craniocerebral perfusion (red-colored vessels on left) and presumed spontaneous external-to-internal carotid reperfusion (red-colored vessels on right), following (sub)total interruption of internal carotid artery perfusion (gray-colored vessels on right) at time of declaration of brain death, and permitting focal cellular reactive changes in superficial cerebral and cerebellar cortices by neovessels branching from middle meningeal artery (right, and inset). (Image credit: Folkerth 2023).

Image: Diagram of normal craniocerebral perfusion (red-colored vessels on left) and presumed spontaneous external-to-internal carotid reperfusion (red-colored vessels on right), following (sub)total interruption of internal carotid artery perfusion (gray-colored vessels on right) at time of declaration of brain death, and permitting focal cellular reactive changes in superficial cerebral and cerebellar cortices by neovessels branching from middle meningeal artery (right, and inset). (Image credit: Folkerth 2023).

- Vascular Changes include congestion, endothelial swelling (ischemic injury to vessels) and thrombosis.

- The interval from brain death to removal of life support is a key determinant of histologic findings.

- <48 hours from brain death: in most cases of brain death, the patient is taken off of life support within a relatively short interval after being pronounced brain dead. In these cases, the changes associated with brain death are predominantly that of extensive ischemic/hypoxemic injury.

- Widespread ischemic neuronal changes (“red dead neurons”): shrunken neurons with pyknotic nuclei, loss of nucleoli, and hypereosinophilic cytoplasm

- Notably, these findings are not due to the loss of perfusion/brain death directly. Ischemic/hypoxic changes take time to evolve and so, when present, are a consequence of the brain injury occurring prior to brain death.

- <48 hours from brain death: in most cases of brain death, the patient is taken off of life support within a relatively short interval after being pronounced brain dead. In these cases, the changes associated with brain death are predominantly that of extensive ischemic/hypoxemic injury.

Short time intervals (days to weeks): autolysis with loss of nuclear detail, variably preserved tissue architecture, and variable tissue washout (loss of details such as cell outlines and nuclei on routine stains). Mineralization can be present.

Image: Example of macroscopic and microscopic features of brain death. Brain from a 33-year-old man with a history of sepsis, extubated 5 days following brain-death declaration, with marked swelling and gray-brown discoloration (A); note relative preservation of architectural relationships on axial cut section, as well as focal petechiae at sites of partial reperfusion (arrows, B). Neurohistology of frontal cortex, with artifactual “fracturing” of devitalized tissue; note stellate crystalline change (arrows, C; 100), and finely granular subpial mineralization (D; 400). Temporal cortex with artifactual “fracturing” of devitalized tissue; this area must have had partial reperfusion to allow neutrophilic influx among hypereosinophilic (ischemic) neurons (E; 400). Pons days following brain-death declaration, with “washed out picture” of devitalized tissue, and no cellular reaction; note red cell outlines visible in vascular lumen (F; 200); ventral subpial region which must have had partial reperfusion to allow inflammatory cell influx (now “washed out,” arrows, G; 200), and reperfusion hemorrhage (site of petechiae in B). (Image credit: Folkerth 2023).

Image: Example of macroscopic and microscopic features of brain death. Brain from a 33-year-old man with a history of sepsis, extubated 5 days following brain-death declaration, with marked swelling and gray-brown discoloration (A); note relative preservation of architectural relationships on axial cut section, as well as focal petechiae at sites of partial reperfusion (arrows, B). Neurohistology of frontal cortex, with artifactual “fracturing” of devitalized tissue; note stellate crystalline change (arrows, C; 100), and finely granular subpial mineralization (D; 400). Temporal cortex with artifactual “fracturing” of devitalized tissue; this area must have had partial reperfusion to allow neutrophilic influx among hypereosinophilic (ischemic) neurons (E; 400). Pons days following brain-death declaration, with “washed out picture” of devitalized tissue, and no cellular reaction; note red cell outlines visible in vascular lumen (F; 200); ventral subpial region which must have had partial reperfusion to allow inflammatory cell influx (now “washed out,” arrows, G; 200), and reperfusion hemorrhage (site of petechiae in B). (Image credit: Folkerth 2023).

Long time intervals (months to years)

- Cases of brain death with a longer post-mortem time interval demonstrate later stages of autolysis including mummification, adipocere formation, and/or maceration.

- Recanalization of superficial vessels (such as the dural venous sinus) can be seen in cases maintained on life support after brain death.

Image: Example of macroscopic and microscopic features of tissue changes in postmortem mummification. Brain and meninges from an adult found in apartment months after last seen alive, with identifiable cerebral hemispheres (A, dorsal view), visible dura (arrow, B), and suggestion of cortical ribbon, with yellow-brown discoloration (arrow, C). Histology of mummified dura with nearly complete retention of architecture and staining quality of dural fibroblasts, vessels, and nerves (arrows, D; 200). Neurohistology of leptomeninges and vessels with fluffy crystalline changes (arrowheads) in underlying cortex which also shows cleft-like spaces (E; 400). Cerebral cortex, with lack of hematoxylin staining, cleft-like spaces, and punctate subpial mineralization (arrows, F; 100, and G; 600); mineralized angular structures consistent with neurons (inset, G, 400). (Image credit: Folkerth 2023).

Image: Example of macroscopic and microscopic features of tissue changes in postmortem mummification. Brain and meninges from an adult found in apartment months after last seen alive, with identifiable cerebral hemispheres (A, dorsal view), visible dura (arrow, B), and suggestion of cortical ribbon, with yellow-brown discoloration (arrow, C). Histology of mummified dura with nearly complete retention of architecture and staining quality of dural fibroblasts, vessels, and nerves (arrows, D; 200). Neurohistology of leptomeninges and vessels with fluffy crystalline changes (arrowheads) in underlying cortex which also shows cleft-like spaces (E; 400). Cerebral cortex, with lack of hematoxylin staining, cleft-like spaces, and punctate subpial mineralization (arrows, F; 100, and G; 600); mineralized angular structures consistent with neurons (inset, G, 400). (Image credit: Folkerth 2023).

Image: Brain death sustained on a ventilator for ~5 months. The laminar-shape to the cortical necrosis is obvious even at low power. (Image credit: John Newman/Stanford Hospital).

Image: Brain death sustained on a ventilator for ~5 months. The laminar-shape to the cortical necrosis is obvious even at low power. (Image credit: John Newman/Stanford Hospital).

Image: Higher power of the above image demonstrates necrosis of layers II-VI of the cortex with relative sparing of layer I due to collateral leptomeningeal circulation. Below Layer I there is diffuse infiltration with macrophages (from the leptomeningeal vessels) with consequent cavitation. Layer I shows reactive astrogliosis. (Image credit: John Newman/Stanford Hospital).

Image: Higher power of the above image demonstrates necrosis of layers II-VI of the cortex with relative sparing of layer I due to collateral leptomeningeal circulation. Below Layer I there is diffuse infiltration with macrophages (from the leptomeningeal vessels) with consequent cavitation. Layer I shows reactive astrogliosis. (Image credit: John Newman/Stanford Hospital).

Image: From the same case as above, the white matter shows retention of tissue architecture overall, with vacuolization and prominent reactive gliosis. (Image credit: John Newman/Stanford Hospital).

Image: From the same case as above, the white matter shows retention of tissue architecture overall, with vacuolization and prominent reactive gliosis. (Image credit: John Newman/Stanford Hospital).

Quick Tips at Time of Reporting

- Example of report comments for cases of brain death with a short time interval (up to a few days)

- “Acutely necrotic (hypereosinophilic) neurons were identified in all brain structures examined. The gross and histopathologic changes are indicative of global cerebral hypoperfusion or recent hypoxemia and are consistent with the clinical diagnosis of brain death.”

- “Secondary patchy cerebral edema, hypoxic-ischemic changes, left uncal herniation, and left subfalcine herniation, and left-to-right midline shift.”

- Report example for longer time course including findings of autolysis:

- “Diffuse hypoxic-ischemic (anoxic) encephalopathy with cerebral edema and autolysis consistent with non-perfused brain.”

- Brain death is not included in the cause of death statement.

Clinical tidbits:

- Brain death is declared in approximately 2% of in-hospital deaths (Seifi 2020).

Recommended References

- Rebecca D Folkerth, John F Crary, D Alan Shewmon, Neuropathologic findings in a young woman 4 years following declaration of brain death: case analysis and literature review, Journal of Neuropathology & Experimental Neurology, Volume 82, Issue 1, January 2023, Pages 6–20

Additional References

- Oechmichen M, Meissner C. Cerebral hypoxia and ischemia: the forensic point of view: a review. J Forensic Sci. 2006 Jul;51(4):880-7. doi: 10.1111/j.1556-4029.2006.00174.x. PMID: 16882233.

- Plum F, Posner JB, Hain RF. Delayed neurological deterioration after anoxia. Arch Intern Med. 1962 Jul;110:18-25. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1962.03620190020003. PMID: 14487254.

- Seifi A, Lacci JV, Godoy DA. Incidence of brain death in the United States. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2020;195:105885

- Ujihira N, Hashizume Y, Takahashi A. [A neuropathological study on respirator brain]. Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 1993 Feb;33(2):141-9. Japanese. PMID: 8319384.