Authors: Andrew Brown, Amogh Nagol, Alyssa Murphy, Samantha Engrav, & Harry Sanchez MD

Background

Aortic Aneurysm

An aortic aneurysm is defined as a local enlargement/“ballooning” of a portion of the aortic wall, predominantly due to degeneration and/or injury of the tunica media (the middle layer of the aorta). An aortic aneurysm is present when there is at least a 50% increase in the aortic diameter. In most cases, this means a diameter of 3 cm or more. The degeneration can be the result of a variety of factors including chronic inflammation, smoking, atherosclerosis, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, infections, increased age, and genetic conditions – especially inherited connective tissue diseases.

Hypertension and atherosclerosis are the most common mechanisms, as cholesterol and lipid accumulation expedite the breakdown of the elastin fibers (that predominate in the tunica media). Subsequent remodeling leads to expansion of the aorta and disruption of laminar blood flow – leading to further remodeling and increased risk of thrombus formation and aneurysm dissection. Abdominal aortic aneurysms are more often associated with atherosclerosis than thoracic aneurysms.

Aneurysms are more likely to form in the abdominal aorta, often between the renal arteries and the bifurcation of the aorta. However, while the abdominal aorta is more likely to develop an aneurysm, thoracic aortic aneurysms are more likely to dissect (most commonly within the first 10 cm of the proximal aorta) due to high pressure from the contracting left ventricle.

Complications of aortic aneurysms include:

- Rupture with life threatening hemorrhage

- Dissection (see below)

- Thrombus formation

- Aortoenteric fistula formation especially with the duodenum

- May occur in native aorta but more common after surgical aneurysmal repair

- Erosion of adjacent vertebral bodies

- Atheroemboli and blue toe syndrome

Aortic Dissection

In aortic dissection, a tear in the tunica intima allows blood under high pressure to create a space (the false lumen) between the intima and the tunica media of the aortic wall.

There are two main classification systems for aortic dissections:

- DeBakey classification includes three types of dissection (I-III) and is less commonly used but more specific when identifying the anatomical location(s) of the aortic dissection.

- Stanford Classification is more commonly used and simplifies aortic dissections into two types. Type A includes the ascending aorta (DeBakey Type I-II) while Type B is distal to the left subclavian artery (DeBakey Type III). This classification focuses on delineating treatment between surgical and medical interventions.

| Stanford | Type A

|

Type B

|

|

| DeBakey | Type I

|

Type II

|

Type III

|

Image: Types of aortic dissections. (Image credit: Healthlines).

Image: Types of aortic dissections. (Image credit: Healthlines).

- The mechanism of aortic dissection includes weakening of the tunica media which allows tearing through the thin intimal layer above and into the media. This may occur due to medial atrophy induced by hypertension-induced hyaline atherosclerosis of the adventitial vasa vasorum or inherent medial weakness induced by a genetic disease such as Marfan syndrome.

- The blood tracks along the media to create a false lumen.

- The blood in the false lumen pulses under high pressure and may

- Re-enter the true aortic lumen through a second downstream intimal defect

- Propagate along the media and impinge on the origins of branches of the aorta (coronary arteries, mesenteric arteries, renal arteries, iliac arteries)

- Rupture through the adventitia causing catastrophic hemorrhage into:

- Pericardium with resulting tamponade

- Pleural space with hemothorax

- Retroperitoneum (hemoperitoneum)

Quick Tips at Time of Autopsy

Clinical History

- Risk factors for aortic aneurysm and dissection include:

-

- Hypertension

- Hyperlipidemia

- Cocaine or amphetamine use

- Recent thoracic trauma

- Genetic syndromes:

- Connective tissue disorders: Marfan’s syndrome, Ehlers Danlos (notably the vascular subtype), Loeys-Dietz syndrome, etc.

- Congenital diseases involving the aorta: Bicuspid aortic valve (Turner’s syndrome), coarctation of the aorta, tetralogy of Fallot, vascular rings/slings with diverticulum of Kommerell

- Tertiary syphilis is a unique infectious risk factor for thoracic aorta aneurysm and dissection

- While rare, pregnancy related changes also pose a risk for aneurysm development

- Chart review may disclose abdominal aortic aneurysm screening imaging (the USPSTF recommends all men who ever smoked ages 65-75 have a one-time abdominal ultrasound screen)

- Any individuals that have signs of an aneurysm may have further imaging to monitor the development of the aneurysm over time

Clinical presentation:

- Aortic aneurysms are often asymptomatic and may be incidentally noticed on imaging

- Patients with aortic dissection often present with sharp tearing chest/abdominal pain that radiates to the back.

- CXR may show a widened mediastinum (>8cm), tracheal shift, and aortic knuckle blurring. However, chest x-ray or ECG may be normal. In the abdomen, ultrasound will show an enlarged region in the aorta.

- Definitive diagnosis can be obtained through CTA (gold standard), TEE, and MRA which can clearly image the dissection demonstrating an intimal dissection flap as well as a double lumen in the aorta.

Image: Axial CTA of a patient with Ruptured Stanford Type A Aortic Dissection. (Image credit: Radiopaedia).

Image: Axial CTA of a patient with Ruptured Stanford Type A Aortic Dissection. (Image credit: Radiopaedia).

External examination

- External exam findings of aortic dissection are usually limited and may be restricted to external examination findings related to underlying genetic conditions, when present. Retroperitoneal hemorrhage from aortic rupture may produce periumbilical ecchymosis (Cullen sign) or flank ecchymosis (Grey Turner sign).

Internal examination

- The internal examination of the aorta during an autopsy provides crucial insights into the extent and nature of the dissection. Breakdown of the internal examination findings in aortic dissection:

- In Type A dissections, it is usually located in the ascending aorta, often within a few centimeters of the aortic valve. In Type B dissections, it typically occurs just distal to the left subclavian artery in the descending aorta.

- Appearance: The tear appears as a transverse or oblique slit in the intima, often several centimeters in length. The edges of the tear may be irregular or smooth, depending on the acuteness of the dissection.

- Multiple Tears: In some cases, there may be multiple intimal tears, which can complicate the dissection pattern and affect treatment strategies.

Image: Types of aortic dissections. (Image credit: Healthlines).

True and False Lumen:

- False Lumen Characteristics: The false lumen is created by the separation of the aortic wall layers. It can be partially or completely filled with thrombus , depending on the chronicity of the dissection. Fresh dissections may have a patent (open) false lumen filled with blood, while chronic dissections may show organized thrombus.

- Size Comparison: Typically, the false lumen is larger than the true lumen due to the pressure exerted by the dissecting hematoma. The false lumen often has a wrinkled or ridged appearance due to the separation of the media layers.

- Communication: In some cases, there may be re-entry sites where the false lumen reconnects with the true lumen, allowing for communication between the two. These re-entry tears are often smaller than the initial intimal tear.

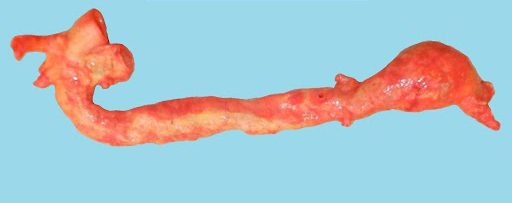

Image: Example of an aneurysm at the bifurcation of the abdominal aorta into the iliac arteries. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington)

Image: Example of an aneurysm at the bifurcation of the abdominal aorta into the iliac arteries. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington)

Extent of Dissection:

- Ascending Aorta: For Type A dissections, the dissection often extends from the ascending aorta to involve the aortic arch and can continue into the descending aorta. The involvement of the aortic root can lead to complications like aortic valve insufficiency.

- Descending Aorta: Type B dissections typically extend from the descending aorta and may continue into the abdominal aorta and its branches. The extent of the dissection should be carefully mapped to understand the potential impact on blood flow to vital organs.

Branch Vessel Involvement:

- Compromised Blood Flow: The dissection can extend into the major arterial branches, leading to compromised blood flow and ischemia. Commonly involved branches include the renal arteries, mesenteric arteries, and iliac arteries. The degree of involvement should be noted to assess the risk of organ damage.

- Ostial Stenosis: The intimal flap can cause narrowing (stenosis) at the origin of the branch vessels, further impairing blood flow and potentially leading to ischemic damage in the organs supplied by these arteries.

Thrombosis and Healing:

- Thrombus Formation: The false lumen may contain thrombus, particularly in chronic dissections. Thrombus formation can be partial or complete and may show varying stages of organization, from fresh red thrombus to older, laminated, and fibrous thrombus.

- Healing and Scarring: In chronic dissections, the false lumen may show signs of healing, with fibrosis and scarring of the dissected layers. The presence of organized thrombus and fibrotic tissue indicates a chronic process

- Reduced Blood Flow: Thrombosis can lead to reduced organ perfusion – potentially causing ischemic complications. This is particularly relevant in cases where distal re-entry tears are occluded, which can lead to higher diastolic pressures and further complications. Documenting the patency of large branches off of the aorta (such as the celiac, SMA, or renal arteries) is critical to identifying potential downstream ischemia.

Associated Complications:

- Aortic Valve Involvement: Type A dissections often involve the aortic root and valve, leading to aortic regurgitation. This can be identified by tears extending into the valve cusps and dilation of the aortic annulus.

- Hemopericardium: In Type A dissections, blood can dissect into the pericardial sac, causing hemopericardium and cardiac tamponade. Cardiac tamponade is the most common cause of death in patients with acute Type A aortic dissection and is a critical finding and often a cause of sudden death.

Image: Images from a patient who died of thoracic aortic dissection and rupture with tamponade. Top: Pericardium opened in situ to reveal hemopericardium. Bottom: Ascending aorta with dissection. (Image credit: Harry Sanchez/Yale New Haven Hospital).

Image: Images from a patient who died of thoracic aortic dissection and rupture with tamponade. Top: Pericardium opened in situ to reveal hemopericardium. Bottom: Ascending aorta with dissection. (Image credit: Harry Sanchez/Yale New Haven Hospital).

- Rupture: The dissection can lead to rupture of the aortic wall, particularly if the adventitial layer is breached. Rupture sites are often found in the thoracic or abdominal aorta and can result in fatal hemorrhage.

Image: Ascending aortic dissection near the aortic valve. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington)

Image: Ascending aortic dissection near the aortic valve. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington)

Ancillary Testing

- Aortic dissection can be diagnosed post-mortem using coronary angiography and/or post-mortem CT. While not widespread, this is increasingly common in the age of the radiographic autopsy.

- Genetic testing may also be considered if a genetic component is likely such as identifying a mutation in the FBN1 gene for Marfan syndrome.

Treatment and Intervention

- Generally, aortic aneurysms are medically managed until the aneurysm reaches a diameter 5.0 cm or greater or the aneurysm has grown rapidly, in which surgery is usually recommended.

- In some cases, a patient with an aneurysm less than 5.0 cm may be treated surgically if there are underlying risk factors, and/or a significant family history

- Surgical interventions can either be open, or through an endovascular approach

- Endovascular repair (EVAR): A graft (usually made of polytetrafluoroethylene – PTFE, or Dacron) is deployed through vascular access (frequently the common femoral artery) that expands and blocks blood flow through the false lumen of the aneurysm.

Image: Endovascular aneurysm repair. (Image credit: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute)

Image: There are multiple kinds of leaks which are common with vascular grafts. Correlating ante-mortem radiography with postmortem findings can help confirm known or previously unidentified leaks. (Image credit: Kassem 2017).

Image: There are multiple kinds of leaks which are common with vascular grafts. Correlating ante-mortem radiography with postmortem findings can help confirm known or previously unidentified leaks. (Image credit: Kassem 2017).

- Open surgery: Similar to an endovascular approach in regard to graft placement, but open incisions are made in the chest or abdomen, with the notable exception that during open surgery, the aorta is clamped during repair

Quick Tips at Time of Histology Evaluation

- Degeneration of the Aortic Tunica Media (Aneurysm Formation)

- The Society for Cardiovascular Pathology and the Association for European Cardiovascular Pathology note that overall medial degeneration can be classified based on the following:

- Mucoid Extracellular Matrix Accumulation (MEMA)

- The deposition of mucoid extracellular matrix is a degenerative process that involves the buildup of basophilic ground substance within the tunica media, displacing lamellar units. It is attributed to aging and connective tissue disorders

- MEMA can be intralamellar (preservation of the arrangement of lamellar units) and/or translamellar (alteration/loss of lamellar units).

- Histological medial degeneration caused by pools of MEMA will show pools of basophilic to translucent pools (depending on stain) of ground substance that are interspersed between and/or displace/fragment lamellar units

- While this can be viewed on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stains, Periodic acid schiff (PAS) stain or elastin stains such as Verhoeff-Van Gieson (VVG), trichrome, and Movat’s pentachrome may better accentuate these changes.

- MEMA has previously also been referred to as: “cystic medial necrosis,” “cystic degeneration,” and “mucoid degeneration”

- Mucoid Extracellular Matrix Accumulation (MEMA)

- The Society for Cardiovascular Pathology and the Association for European Cardiovascular Pathology note that overall medial degeneration can be classified based on the following:

Image: (A and B) Translamellar MEMA on H&E and Movat’s pentachrome at 100x. (C and D) Intralamellar MEMA on H&E and Movat’s pentachrome at 100x. (Image credit: Halushka et al. 2016)

Image: (A and B) Translamellar MEMA on H&E and Movat’s pentachrome at 100x. (C and D) Intralamellar MEMA on H&E and Movat’s pentachrome at 100x. (Image credit: Halushka et al. 2016)

- Elastic fiber fragmentation, thinning, disorganization, and/or loss

- A normal aorta has dense elastic fiber networks in each lamella. Fragmentation and/or loss of elastin fibers weakens the structural integrity of the aortic wall (and predisposes it to dissection)

- Loss of elastic fibers results in a thinning of the lamellar unit leading to band-like loss of elastic fibers and smooth muscle cells

- These changes are best appreciated using elastic fiber stains and indicate loss of elastic fibers through gaps in elastic fiber lamellae

Image: (A) Elastic fiber fragmentation Movat’s pentachrome 400x. (B) Patch of total elastic fiber loss Movat’s pentachrome 400x. (Image credit: Halushka et al. 2016)

Image: (A) Elastic fiber fragmentation Movat’s pentachrome 400x. (B) Patch of total elastic fiber loss Movat’s pentachrome 400x. (Image credit: Halushka et al. 2016)

- Smooth muscle cell nuclei loss

- Regions of the aorta may show smooth muscle nuclei loss (involving multiple lamellae) – best appreciated on H&E stains

- Has previously been described as “smooth muscle cell necrosis” and “medionecrosis”

- In rare cases, smooth muscle cell disorganization may be appreciated in the outer tunica media (suggests a genetic aortopathy)

- Regions of the aorta may show smooth muscle nuclei loss (involving multiple lamellae) – best appreciated on H&E stains

Image: (A) Patchy smooth muscle cell nuclei loss H&E 200x. (B) Band-like smooth muscle cell nuclei loss H&E 160x. (Image credit: Halushka et al. 2016)

Image: (A) Patchy smooth muscle cell nuclei loss H&E 200x. (B) Band-like smooth muscle cell nuclei loss H&E 160x. (Image credit: Halushka et al. 2016)

- Medial fibrosis

- Following an initial insult to the tunica media, collagen fiber production replaces damaged/lost elastic fibers and can cause a widening of intralamellar spaces

- Can be intralamellar (collagen deposition does not alter lamellar unit arrangement) and translamellar (collagen deposition alters lamellar unit arrangement)

Image: (A) Intralamellar fibrosis (blue) Masson’s trichrome 100x. (B) Translamellar fibrosis Masson’s trichrome 100x. (Image credit: Halushka et al. 2016)

Image: (A) Intralamellar fibrosis (blue) Masson’s trichrome 100x. (B) Translamellar fibrosis Masson’s trichrome 100x. (Image credit: Halushka et al. 2016)

- Dissection Plane: The tear in aortic dissection typically originates in the tunica intima layer and extends into the tunica media, resulting in a separation of the aortic layers. This tearing into the media results in a false lumen filled with blood, located between the outer and inner media or intima. The dissection can extend along the entire length of the aorta, and this separation between layers may become more pronounced in histology sections, especially when stained appropriately.

Immunohistochemistry

- Special Staining Techniques: Stains such as Elastica van Gieson or Movat’s pentachrome can be used to highlight changes in the elastic fibers. These stains help differentiate the disrupted elastic tissue from surrounding structures, making it easier to identify areas of elastin loss or fragmentation. As such, stains that highlight elastic fibers can distinctly show the breaks in continuity of the tunica media, while normal areas will show more uniform and intact fibers.

Image: Example of a dissection of a small artery stained with Movat (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington)

Image: Example of a dissection of a small artery stained with Movat (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington)

- Haematoxylin and eosin stain or a Verhoeff-Van Gieson (elastic) stain to help identify accumulation of mucoid extracellular matrix accumulation (MEMA) in aortic walls

Image: Low (above) and high (below) power example of a dissection of a small artery stained with H&E (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington)

Image: Low (above) and high (below) power example of a dissection of a small artery stained with H&E (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington)

- Findings of disease processes which predispose to dissection may also be present such as giant cell arteritis and, more commonly, atherosclerosis.

Quick Tips at Time of Reporting

- Documenting the type of the dissection, extent of the dissection, and associated tamponade and/or soft tissue hemorrhage is critical

- Example cause of death statements

- Cardiac tamponade due to Type A aortic dissection. Hypertension is a contributing factor.

- Massive abdominal hemorrhage due to type B aortic dissection due to atherosclerosis

Clinical Tidbits

- The status of thrombosis in the false lumen can heavily influence treatment decisions. For instance, in patients with type B aortic dissection, those presenting with partially thrombosed false lumens have shown increased complication rates and surgical mortality. As such, this can affect management strategies, including the choice between medical therapy or surgical intervention.

Recommended References:

- Halushka MK. et al. Consensus statement on surgical pathology of the aorta from the Society for cardiovascular Pathology and the association For European Cardiovascular pathology: II. Noninflammatory degenerative diseases – nomenclature and diagnostic criteria. Cardiovascular Pathology. 2016; 25:257-257.

- Hiroaki Osada, Masahisa Kyogoku, Tekehiko Matsuo, Naoki Kanemitsu, Histopathological evaluation of aortic dissection: a comparison of congenital versus acquired aortic wall weakness, Interactive CardioVascular and Thoracic Surgery, Volume 27, Issue 2, August 2018, Pages 277–283, https://doi.org/10.1093/icvts/ivy046

Additional References:

- Levy D, Sharma S, Grigorova Y, et al. Aortic Dissection. [Updated 2024 Oct 6]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441963/

- Hiroaki Osada, Masahisa Kyogoku, Tekehiko Matsuo, Naoki Kanemitsu, Histopathological evaluation of aortic dissection: a comparison of congenital versus acquired aortic wall weakness, Interactive CardioVascular and Thoracic Surgery, Volume 27, Issue 2, August 2018, Pages 277–283, https://doi.org/10.1093/icvts/ivy046

- Zhang, S., Sun, W., Liu, S., Song, B., Xie, L., & Liu, R. (2023). Does False Lumen Thrombosis Lead to Better Outcomes in Patients with Aortic Dissection: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. The Heart Surgery Forum, 26(5), E628-E638. https://doi.org/10.59958/hsf.5739

- Tolenaar, J., Eagle, K., Jonker, F., Moll, F., Elefteriades, J., & Trimarchi, S. (2014). Partial thrombosis of the false lumen influences aortic growth in type B dissection. Annals Of Cardiothoracic Surgery, 3(3), 275-277. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2225-319X.2014.04.01

- Davis FM., Daugherty AD., Lu HS. Updates of Recent Aortic Aneurysm Research. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2019; 39(3):83-90. Updates of Recent Aortic Aneurysm Research

- Cho MJ., Lee MR., Park JG. Aortic aneurysms: current pathogenesis and therapeutic targets. Experimental & Molecular Medicine. 2023; 55:2519-2530. Aortic aneurysms: current pathogenesis and therapeutic targets

- Harky A., Sokal PA., Hasan K., Papaleontiou A. The Aortic Pathologies: How Far We Understand It and Its Implications on Thoracic Aortic Surgery. Braz J Cardiovasc Surg. 2021; 36(4): 535-549. The Aortic Pathologies: How Far We Understand It and Its Implications on Thoracic Surgery

- Aggarwal S., Qamar A., Sharma V., Sharma A. Abdominal aortic aneurysm: A comprehensive review. Exp Clin Cardiol. 2011; 16(1):11-15. Abdominal aortic aneurysm: A comprehensive review

- Chaer R. Endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Updated 2023. Endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm