Authors: Jennifer Merk, Robert Hennis, Krishna L. Bharani

Background

Dementia is an umbrella term used to describe significant cognitive decline that interferes with everyday activities. The most common cause of dementia is Alzheimer’s disease (AD), a progressive neurodegenerative disease characterized by extracellular accumulation of beta-amyloid (Aβ) protein (‘plaques’) and intraneuronal aggregates of hyperphosphorylated tau protein (‘neurofibrillary tangles’) leading to damage to brain tissue and significant cognitive decline.

Clinically, AD can be classified as early-onset AD and late-onset AD. Early-onset AD accounts for less than 5% of all AD cases and are largely caused by mutations in proteins involved in creating beta-amyloid protein (i.e., amyloid precursor protein, presenilin 1, and presenilin 2). Late-onset AD (also known as sporadic AD) accounts for the vast majority of all AD cases. It is found in people over the age of 65 and is considered to be not heritable. Although the definitive cause of late-onset AD is unclear, several risk factors have been identified. Age is by far the greatest risk factor for late-onset AD. It is important to recognize that AD and dementia is not a normal part of aging. Age alone is not sufficient to cause Alzheimer’s dementia. Cardiovascular disease, lifestyle, and environment toxins have also been identified as risk factors of late-onset AD. Genetically, the e4 form of the apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene has the strongest impact on the risk of late-onset AD.

Although great advances have been made in diagnosing AD clinical, post-mortem neuropathologic evaluation remains the gold-standard to definitive diagnosis of AD. In addition, neuropathologic evaluation is important to identify co-neuropathologies. Approximately 50% of persons clinically diagnosed with probable AD have neuropathologic evidence of other neurodegenerative diseases and vascular disease in addition to AD neuropathologic changes (PMID: 28488154).

Workup for neurodegenerative changes is typically based on a clinical history of cognitive decline, although some academic institutions perform a neurodegenerative workup for any patient over a certain age (65 year-old for example) regardless of cognitive status.

Quick Tips at Time of Autopsy

Clinical history

- Check the clinical history for mentions of cognitive decline.

- Neurologists and/or neuropsychiatrists notes are particularly high yield.

- Evidence of cognitive decline

- Neurologists often screen for mild cognitive impairment using a MOCA or MMSE. These exams are more useful in the early stages of impairment and have a low predictive value for identifying those who will develop dementia.

- Neuropsychologists use comprehensive cognitive and behavioral assessments to assess potential neurodegenerative disease

- Fluid biomarkers of neurodegeneration

- CSF can show decreased beta-amyloid protein and/or increased total tau protein (t-tau) or increased phosphorylated tau protein (p-tau)

- Neuroimaging evidence of neurodegeneration

- MRI might mention cortical atrophy, also look for mentions of strokes

- Special amyloid or tau PET studies are increasingly common in the clinical work up of AD

Image: MRI of a normal control (right) and a patient with advanced Alzheimer’s Disease (left). Note the widened sulci, enlarged ventricles, and gaping temporal horns in the patient with AD, reflecting cortical and hippocampal atrophy. (Image credit: J. Growdon/Massachusetts Hospital published in Smith 2024/Greenfield’s Neuropathology).

- Click here for extra reading on the revised criteria for diagnosis and staging of Alzheimer’s disease from the Alzheimer’s Association Workgroup

Ancillary testing

- AD patients can have genetic mutations. But genetic screening is not standard at autopsy and is driven primarily by research or clinical concern in the antemortem setting.

External body examination

While there are no specific external examination signs for patients with neurodegenerative disease, the end stage of the disease process is associated with severe physical impairment signs including

- Weight loss and poor nutrition: this can be due to a combination of factors such as poor appetite, difficulties in swallowing (dysphagia), reduced ability to self-feed, and AD-related apathy leading to self neglect of nutritional needs. This can lead to muscle wasting and frailty.

- Skin Issues: Poor nutrition and immobility can lead to skin problems, such as pressure sores/ulcers.

- Poor Hygiene and Grooming: As cognitive functions decline, patients may neglect personal hygiene and grooming. This can result in an unkempt appearance, body odor, and other signs of poor self-care.

- Signs of caregiver neglect such as untreated bed sores, lice, being unwashed, etc. may warrant reporting the case to the medical examiner’s office.

- Dehydration: Patients may have dry skin and mucous membranes due to inadequate fluid intake. Dehydration can be a serious issue in advanced Alzheimer’s disease.

- Infections: The immune system can be compromised, leading to an increased susceptibility to infections including skin infections (but also urinary tract infections and respiratory infections which would be part of the internal examination).

- Dental Issues: Poor oral hygiene can lead to dental problems such as cavities, gum disease, and tooth loss.

External brain examination

- Classic gross brain examination findings for AD include

- Diffuse cerebral atrophy, often with frontotemporal predominance sparring the occipital lobes (although occipital lobes are involved in more advanced cases).

-

-

- Ventricular enlargement

- Hippocampal atrophy

- Loss of pigmentation in the locus coeruleus (also seen in Lewy Body Dementia)

-

- None of these findings are specific to AD

Images: Gross Anatomy of Alzheimer’s patient’s brain (lower image) compared to a reference brain (upper image). Cortical atrophy is highlighted by the arrowheads. Enlargement of the frontal and temporal horns of the lateral ventricles are highlighted by the arrows. Loss of pigmented neurons in the locus coeruleus is highlighted by the open circle. (Image credit: DeTure et al. 2019).

Images: Gross Anatomy of Alzheimer’s patient’s brain (lower image) compared to a reference brain (upper image). Cortical atrophy is highlighted by the arrowheads. Enlargement of the frontal and temporal horns of the lateral ventricles are highlighted by the arrows. Loss of pigmented neurons in the locus coeruleus is highlighted by the open circle. (Image credit: DeTure et al. 2019).

Image: Hippocampal volume loss results in extra space around the hippocampus (right hippocampus). This photo shows relative preservation of the hippocampus on the left; a nice internal control in this non-AD case. (Image credit: Adventures in Neuropathology).

Image: Hippocampal volume loss results in extra space around the hippocampus (right hippocampus). This photo shows relative preservation of the hippocampus on the left; a nice internal control in this non-AD case. (Image credit: Adventures in Neuropathology).

Gross brain sampling

- Sampling should have broad coverage for the most common NDD’s given the possibility for misclassification based on clinical presentation and/or multiple coexisting processes

-

- The Updated Condensed Protocol from Multz et.al, offers a cost-effective method to test for AD as well as other major ND diseases.

- The protocol is validated to diagnose AD as well as Lewy Body Disease, cerebral amyloid angiopathy, LATE, AGD, PART, and vascular dementia. FTLD would also be detected but may need additional sections/stains for full diagnosis.

Image: The condensed protocol for neurodegenerative disease uses 5 blocks to sample all of the routine screening sections for common neurodegenerative diseases. Each block gets one or two immunohistochemical stains (in addition to an H&E) in order to minimize cost. (Image credit: Multz, et al 2023).

Image: The condensed protocol for neurodegenerative disease uses 5 blocks to sample all of the routine screening sections for common neurodegenerative diseases. Each block gets one or two immunohistochemical stains (in addition to an H&E) in order to minimize cost. (Image credit: Multz, et al 2023).

Quick Tips at Time of Histology Evaluation

Histology

- The H&E stain of cortex with AD changes can show many diagnostic and incidental findings as demonstrated by the following photos

Image: Background changes of moderate to severe neurodegenerative disease (left) demonstrating background neuropil vacuolization compared to control brain parenchyma (right). (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

Image: Background changes of moderate to severe neurodegenerative disease (left) demonstrating background neuropil vacuolization compared to control brain parenchyma (right). (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

Image: Neurons may contain vacuoles with dense granules (granulovacuolar degeneration, white arrow heads) or pink intracytoplasmic inclusions that often appear to be overlapping the edge of the cell body (Hurano bodies, red arrow head). (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/Stanford Hospital).

Image: Neurons may contain vacuoles with dense granules (granulovacuolar degeneration, white arrow heads) or pink intracytoplasmic inclusions that often appear to be overlapping the edge of the cell body (Hurano bodies, red arrow head). (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/Stanford Hospital).

Image: Neurofibrillary tangles can also be seen on H&E as fibrillar purple inclusions (white arrows). (Image credit: Krishna L. Bharani, Stanford Hospital).

Image: Neurofibrillary tangles can also be seen on H&E as fibrillar purple inclusions (white arrows). (Image credit: Krishna L. Bharani, Stanford Hospital).

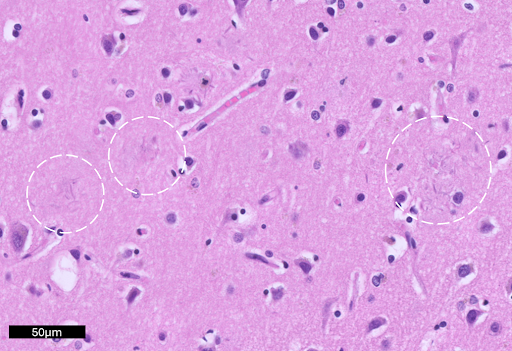

Image: Amyloid-beta plaques in the cortex are highlighted by white circles. On H&E, these plaques can be hard to identify and generally appear as distortion in the neuropil containing amorphous proteinaceous debris (Image credit: Krishna L. Bharani/Stanford Hospital).

Image: Amyloid-beta plaques in the cortex are highlighted by white circles. On H&E, these plaques can be hard to identify and generally appear as distortion in the neuropil containing amorphous proteinaceous debris (Image credit: Krishna L. Bharani/Stanford Hospital).

Quick Tips at Time of Reporting

- The most common cause of death for a patient with AD is aspiration pneumonia. Other considerations include heart disease, stroke, and sepsis.

- The presence of Alzheimer’s disease neuropathologic change (i.e., plaques and tangles) can (and should) be reported even when there are no clinical records of Alzheimer’s disease or dementia.

ABC Alzhemier’s Disease score from the NIAA

- Hint: Keep the Coding Guidebook from the NACC Neuropathology Form handy as a reference.

- We also suggest this Cheat Sheet which is a quick reference for all major neurodegenerative conditions covered by the condensed protocol.

- The postmortem diagnosis of AD requires:

- The presence of tau-positive neurofibrillary tangles AND amyloid beta plaques

- Their respective distributions through the cortex, hippocampus, and brainstem, determines the NIAA ABC Score; higher scores correlate with a greater burden of AD changes.

A-score ( Thal phase/amyloid plaque distribution)

The amyloid beta plaques seen in AD typically progress from the cortex, down through the basal ganglia, the midbrain, and finally the cerebellum. To get the Thal phase, assign a number to each location using the cheat sheet. The Thal phase can then be translated to the A-score as follows (Thal 1 or 2 = A1, Thal 3 = A2, Thal 4 or 5 = A3).

Image: Dense and diffuse Amyloid-β plaques in gray matter of cortex (using the 6e10 IHC antibody). Only one plaque is needed in a given area to assign the corresponding Thal phase. (Image credit: Jen Merk/University of Washington).

Image: Dense and diffuse Amyloid-β plaques in gray matter of cortex (using the 6e10 IHC antibody). Only one plaque is needed in a given area to assign the corresponding Thal phase. (Image credit: Jen Merk/University of Washington).

B-score (Braak stage /Tau tangle distribution)

The neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) seen in AD typically progress from hippocampus to the non-motor cortex to the motor/sensory cortex. Assign a number to each location using the cheat sheet, that is the Braak phase. The Braak phase can then be converted to the B-score as follows (Braak I or II = B1, Braak III or IV = B2, Braak V or VI = B3). Click here for a diagram of hippocampal anatomy for Braak I-III).

Of note, a patient with NFTs (on tau) and a low Thal score (on beta-amyloid) can be classified as PART (primary age-related tauopathy). Any Braak score (I-IV) with a Thal of zero is “Definite PART” while a Thal of 1-2 is “Possible PART.” (Thal 3 or higher indicates the traditional ABC NIAA scoring for AD should be used and not the designation of PART).

Image: Tau staining can reveal a network of background neurites, neurofibrillary tangles, and pre-tangles. True NFTs have a fibrillar pattern to the staining (strings of tau, sometimes referred to hair-like) while pre-tangles, which do not count towards the BRAAK stage, are granular in their staining pattern. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

Image: Tau staining can reveal a network of background neurites, neurofibrillary tangles, and pre-tangles. True NFTs have a fibrillar pattern to the staining (strings of tau, sometimes referred to hair-like) while pre-tangles, which do not count towards the BRAAK stage, are granular in their staining pattern. (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

C-score (CERAD/Density of neuritic plaques)

Neuritic plaque are amyloid plaques that also contain tau positive dystrophic neurities (seen via immunohistochemistry or silver impregnation). These neuritic plaques often have dense amyloid cores. The CERAD score captures the density of neocortical neuritic plaques.

- Sparse (up to 5 per 10x field)

- Moderate (6-20 per 10x field)

- Severe (>20 per 10x field)

Image: Example for reference of Bielschowski silver stain positive neuritic plaques with dense cores (white arrows). These are in contrast to amyloid plaques without dense cores which do not count for CERAD (red arrows). (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

Image: Example for reference of Bielschowski silver stain positive neuritic plaques with dense cores (white arrows). These are in contrast to amyloid plaques without dense cores which do not count for CERAD (red arrows). (Image credit: Meagan Chambers/University of Washington).

NIAA Alzheimer’s Disease Neuropathologic Change (ADNC)

Once you have an ABC score, you can use the following table to interpret your findings and make a determination if the neuropathologic change is sufficient explanation for dementia.

(Image credit: Montine et. al 2012)

Click here for some recommended comments for the NIAA AD Score.

Recommended References

- DeTure MA, Dickson DW. The neuropathological diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurodegener. 2019;14(1):32. Published 2019 Aug 2. doi:10.1186/s13024-019-0333-5

- Jack CR Jr, Andrews JS, Beach TG, et al. Revised criteria for diagnosis and staging of Alzheimer’s disease: Alzheimer’s Association Workgroup. Alzheimers Dement. 2024 Aug;20(8):5143-5169. doi: 10.1002/alz.13859.

- Flanagan ME, Marshall DA, Shofer JB, et al. Performance of a Condensed Protocol That Reduces Effort and Cost of NIA-AA Guidelines for Neuropathologic Assessment of Alzheimer Disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2017;76(1):39-43. doi:10.1093/jnen/nlw104

- Montine TJ, Phelps CH, Beach TG, et al. National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease: a practical approach. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123(1):1-11. doi:10.1007/s00401-011-0910-3

Additional References

- Boon BDC, Bulk M, Jonker AJ, et al. The coarse-grained plaque: a divergent Aβ plaque-type in early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2020;140(6):811-830. doi:10.1007/s00401-020-02198-8

- Braak H, Alafuzoff I, Arzberger T, Kretzschmar H, Del Tredici K. Staging of Alzheimer disease-associated neurofibrillary pathology using paraffin sections and immunocytochemistry. Acta Neuropathol. 2006;112(4):389-404. doi:10.1007/s00401-006-0127-z

- Brenowitz WD, Hubbard RA, Keene CD, et al. Mixed neuropathologies and estimated rates of clinical progression in a large autopsy sample. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13(6):654-662. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2016.09.015

- Cullinane PW, Wrigley S, Bezerra Parmera J, et al. Pathology of neurodegenerative disease for the general neurologist. Pract Neurol. 2024;24(3):188-199. Published 2024 May 29. doi:10.1136/pn-2023-003988

- DeTure MA, Dickson DW. The neuropathological diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurodegener. 2019;14(1):32. Published 2019 Aug 2. doi:10.1186/s13024-019-0333-5

- Flanagan ME, Marshall DA, Shofer JB, et al. Performance of a Condensed Protocol That Reduces Effort and Cost of NIA-AA Guidelines for Neuropathologic Assessment of Alzheimer Disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2017;76(1):39-43. doi:10.1093/jnen/nlw104

- Smith C, Thomas J, Gabor K, Perry A. Greenfield’s Neuropathology. 10th Edition; volume 1. CRC Press. 2024.

- Jack CR Jr, Andrews JS, Beach TG, et al. Revised criteria for diagnosis and staging of Alzheimer’s disease: Alzheimer’s Association Workgroup. Alzheimers Dement. 2024 Aug;20(8):5143-5169. doi: 10.1002/alz.13859.

- Mirra SS, Heyman A, McKeel D, et al. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD). Part II. Standardization of the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1991;41(4):479-486. doi:10.1212/wnl.41.4.479

- Montine TJ, Phelps CH, Beach TG, et al. National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease: a practical approach. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123(1):1-11. doi:10.1007/s00401-011-0910-3

- Multz RA, Spencer C, Matos A, et al. What every neuropathologist needs to know: condensed protocol work-up for clinical dementia syndromes. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2023;82(2):103-109. doi:10.1093/jnen/nlac114